Taphouse’s 1743 Hass clavichord. By kind permission of the Bate Collection, Faculty of Music, University of Oxford. Copyright © 2016

T.W. Taphouse and early keyboards

In 1857, when he was aged just 19, Taphouse bought “a remarkably fine harpsichord by Shudi and Broadwood [made in 1773]” which “led me to take an interest in the history and development of keyboard-stringed instruments”. It made only 13 shillings (currently 65 pence!) at an estate auction in Banbury; Taphouse paid the purchaser £2. 10 shillings and sold it on to Messrs. Broadwood in London for £15.

In the same year, Taphouse met A.J. Hipkins (a well-known authority of the time on the piano and its predecessors, and author of several books and 134 articles in Grove), who “gave me many valuable hints upon the restoration of old instruments”, and with whom he corresponded for “upwards of forty years”.

Taphouse restored several keyboards, which he subsequently lent out for lectures and concerts, and displayed (with various rare scores, books and other instruments) at large events, such as the International Inventions Exhibition, 1885; the Musical and Art Exhibition at the Royal Aquarium, 1892; and the Music Loan Exhibition, celebrating the tercentenary of the Worshipful Company of Musicians, held at the Fishmongers’ Hall in 1904.

Although he is known to have been a pianist and church organist, there is no record of him ever having played the harpsichord in public. His step-daughter, Nellie Woodward-Taphouse, however, was “an excellent performer of the harpsichord [and clavichord], having made it a special study”. She gave concerts from at least 1894, and a critic from the Musical Times wrote, “We fervently hope Miss Taphouse will let us hear more of these beautiful old instruments and their truly lovely music on future occasions.” Her obituary (she died, aged 39, in September 1908) also mentions that “She was closely and skillfully associated with Misses Chaplin in their concerts of Ancient Music and Dances …”

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

Aptly, the Bate Collection, in Oxford now has three of Taphouse’s most admired instruments: a superb Shudi & Broadwood two-manual harpsichord of 1781 (listen to it here), a beautiful little spinet by John Harrison of London dated 1749 (listen to it here), and a magnificent five-octave clavichord by Hieronymus Albrecht Hass built in 1743 (listen to it here).

Other instruments owned by Taphouse:

Harpsichords:

- A 17th-century Italian “clavicembalo, compass 3 and 6/8 octaves, C to E, two stops, enclosed in a white painted deal case, and containing an oil painting of Pan on the lid, 5ft. 9 by 2ft. 6, complete on three pedestals”. According to the late Margaret Campbell, in Dolmetsch: The Man and his Work, this instrument was restored by AD in 1894; it’s unknown from whom Taphouse obtained it.

- Jacob Kirkman two-manual (1744), now in private ownership, on permanent loan to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. See here for photos and details.

- Jacobus and Abraham Kirkman two-manual (1775), lent to Nellie Chaplin from 1904. This may have been the instrument which Gustav Leonhardt bought from Raymond Russell in 1957.

Spinets/ Virginals:

- Italian pentagonal spinet, 16th century, compass 4 octaves and 1 note, E to F. “The case is decorated with floriated designs in black, and a number of small ivory nobs or buttons.” It has no maker’s name, but is (according to an exhibition catalogue) exactly similar in size and shape to one by Marcus Jadra, dated 1568, in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

- Italian Virginals c. 1600, “in the original wooden case”.

- 17th-century Italian “Spinetta of 3 and 5/8 octaves, with a decorated case”.

- Three more spinets by Charles Haward (1683), Edmund Blunt (1703), and Joseph Baudin (1723).

Clavichords:

- Nicola Palazzi clavichord (1749).

- A five-octave unfretted clavichord by Johann Gotthelf Hoffmann (1784), now at Yale University. See below.

- Clavichord by Joh. Paul Kraemer und Soehnen (1803),

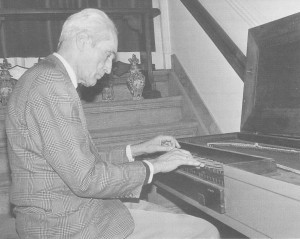

Gustav Leonhardt and the Kraemer clavichord in 1998. By kind permission of Jan Raas. Copyright © 2016

previously owned by Carl Engel (1818–1882), much of whose famous instrument collection went to the South Kensington (now Victoria & Albert) Museum. This clavichord later belonged to Cecil Clutton, who bequeathed it in 1991 to Gustav Leonhardt; it is now in the possession of Menno van Delft, who had it restored in 2015.

Square pianos (interestingly, no grands):

- Johannes Zumpe (1767)

- Pohlman (1769)

- Broadwood (c.1780) with a compass of only 3 octaves

- Broadwood (1796)

As Taphouse was actively collecting for almost 50 years (apart from possibly having taken old instruments in part-exchange for pianos from his flourishing music shop), we may safely assume that many more early keyboards passed through his hands than those listed.

If you know the current location of any of the instruments mentioned above, please let us know, via the comments box

Harpsichord music

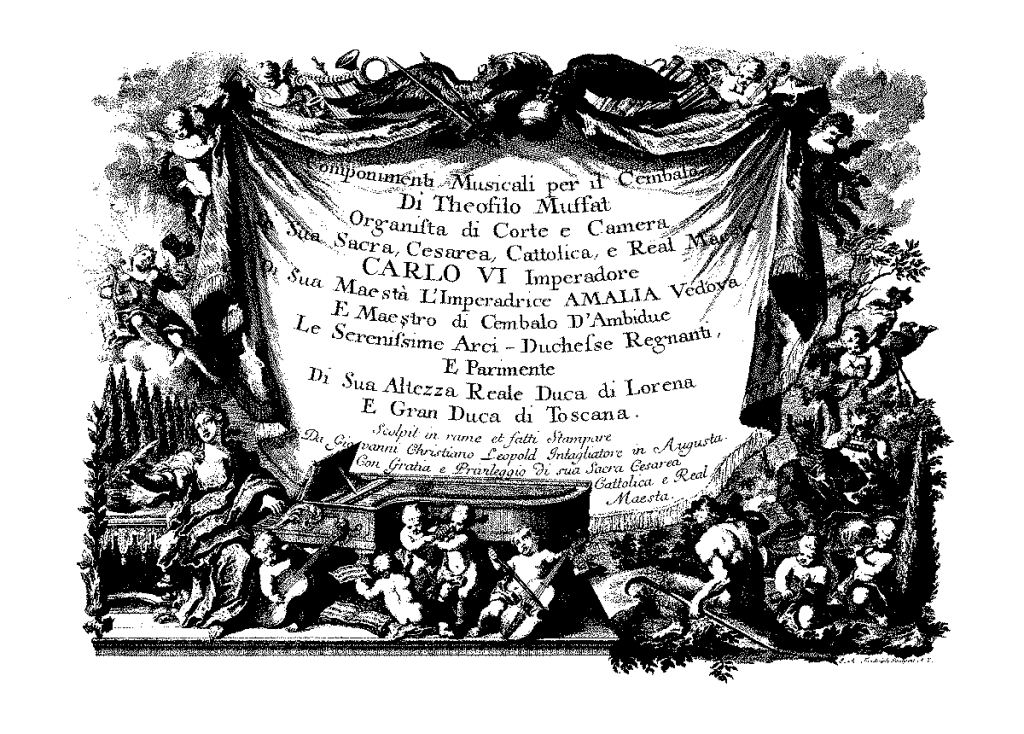

Gottlieb Muffat – “Componimenti musicali per il cembalo” (1739, described by the composer as “the most beautiful product to be met with in all of Germany”; it was certainly one of the most lavish examples of 18th-century music printing.

Taphouse’s library contained 195 volumes of manuscripts and early editions of harpsichord music, including more than a yard of shelf space of sonatas, suites and “Favourite Lessons”, along with the following titles:

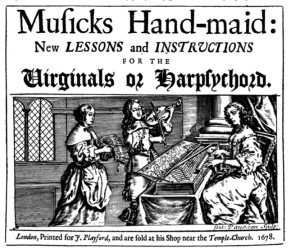

Charles Burney’s copy (apparently unique) of Mattheson’s Pièces de clavecin … en deux volumes (1714); a manuscript Harpsichord Book from the harpsichord maker, Jacob Kirkman; D’Anglebert – Pièces de Clavecin; Charles Avison – 8 Concertos; F. Couperin – Pièces de Clavecin, 2 vols. (1713); Frescobaldi – Toccate d’intavolatura (1637); Froberger – Toccate, canzone … (1693); Krieger’s Anmuthige Clavierübung … (1699, “autograph of J.S. Smith” [sic] probably J.C. Smith, Handel’s amanuensis); Byrd, Bull and Gibbons – Parthenia (1655); Gottlieb Muffat – Componimenti musicali per il cembalo (1739); John Playford – Musick’s Hand-maid: New Lessons and Instructions for the Virginals or Harpsichord;  Purcell – A Choice Collection of Lessons (1696); Rameau – Pièces de clavecin en concerts (1741); and a taste of the exotic, in the form of The Oriental Miscellany … favourite Airs of Hindoostan adapted [by William Hamilton Bird] for the harpsichord (Calcutta, 1789), recently recorded on a Kirkman by Jane Chapman.

Purcell – A Choice Collection of Lessons (1696); Rameau – Pièces de clavecin en concerts (1741); and a taste of the exotic, in the form of The Oriental Miscellany … favourite Airs of Hindoostan adapted [by William Hamilton Bird] for the harpsichord (Calcutta, 1789), recently recorded on a Kirkman by Jane Chapman.

Taphouse also owned the two parts of Diruta’s Il Transilvano (in editions from 1625 and 1622); Couperin – L’art de toucher le clavecin (1717, acquired at least thirteen years before Dolmetsch got his copy, on his 45th birthday in 1903); Locke’s Melothesia (1673) and 15 other thorough-bass tutors. His unique copy of “Richard Aylward’s curious MS. book of lute and harpsichord music” (c. 1640, now lost) was mentioned in a warm appreciation of Taphouse and his “rich collection”, in the preface of Edward Dannreuther’s Musical Ornamentation (1893).

When Taphouse met Dolmetsch

When Arnold Dolmetsch burst onto the early music scene in the 1880s, Taphouse had already been collecting for more than 20 years. We don’t know much about their relationship, other than the fact that AD exchanged a “precious little book” (we don’t know what) for a five-octave unfretted clavichord made by Johann Gotthelf Hoffmann in 1784, which he subsequently sold during his American stay to the heiress, Belle Skinner, for the astronomical price of $1,000.

There may also have been other trades between them, but there is no record of them.

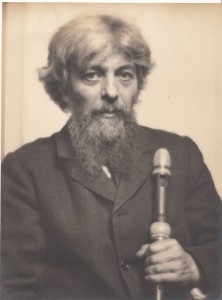

Arnold Dolmetsch and his Bressan recorder. By kind permission of the Dolmetsch Trust. Copyright © 2016

When Taphouse’s collection came up for auction in 1905, Dolmetsch was initially interested in buying a virginals which, ultimately, he found too expensive, at £12. Via a Mr Thompson, he did buy, for £2, a recorder (in lot 111, with two flageolets) which was erroneously catalogued as being made by “Barton”, but was actually a treble recorder of c. 1730 (now in the Horniman Museum) by Peter Bressan (1663–1731), on which Dolmetsch was to base the instrument that started a revolution.

Watch this fascinating video on the recent technical analysis into the exceptional tonal qualities of a similar Bressan recorder from 1720

From the book sale, he obtained a recorder tutor: the Compleat Flute Master (1695), which he desperately needed in order to learn to play the Bressan properly. According to the auctioneer’s ledger, previously overlooked, this was bought on AD’s behalf by Beatrice Horne, a viol-playing friend and a very generous benefactor (see Campbell), as AD was on the boat to the USA at the time the auction was held.

Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation has recently found a diary entry for an appointment with Miss Horne on 20 October 1910, on his return from America, and has suggested that the Compleat Flute Master changed hands then. This would explain why AD did not play the recorder in public till a concert in Perth in 1912. Dr Blood has written about all this in the Autumn 2015 issue of the Foundation’s Bulletin.

Summing up

As well as his post-mortem influence on the career of Arnold Dolmetsch, Taphouse played an important role in the revival of the harpsichord and clavichord and, like Carl Engel before him, no doubt saved many instruments from being broken up for firewood.

Unfortunately, Taphouse left no writings, other than the hand-written catalogue of his keyboard instruments and publications in his library relating to the history of the piano, that he made in 1890. It’s clear from these descriptions, and from the annotations he left in the books and scores he owned, that he was extremely knowledgeable and took the whole business of collecting very seriously. His library contained long runs of academic journals, contemporary books in German, Italian and French, and a wide range of bibliographical source material (such as auction and publishers’ catalogues), some of which he had bound together in 27 volumes.

Given the fame of Taphouse’s collection, it’s surprising that no attempt was made to keep it together. Of the 2,000-plus rare and unique items in his library, most have disappeared without trace. Apart from the haul at Leeds, the British Library has 14 items known to have belonged to Taphouse; the Bodleian has around 20; and the Library of Congress holds a single lot from the book sale, consisting of 23 bound volumes of assorted pamphlets and musical tracts.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Faye Belsey, Assistant Curator, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford; Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation; Menno van Delft; Andrew Lamb, Curator of the Bate Collection; Thomas MacCracken; Gilly Margrave, Librarian (Music and Drama), Leeds Library and Information Service; Dr Rupert Ridgewell, Christopher Scobie and Claire Wotherspoon of The British Library; James L. Wallmann; and Dr Alexandra Williams, whose The Dodo was really a phoenix: the renaissance and revival of the recorder in England 1879–1941, has been a valuable source. You can download the whole thing (400 pages!) here.

If you appreciate this blog post, please share this link //bit.ly/1ZsLfHb with your friends.

Copyright © 2016 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

Did taphouse have an ex-libris or other way of marking books from his library?

Aaron

1)There’s a volume of keyboard stuff by Ayleward in a late 19th cent Ms copy, asociated with Taphouse in the catalogue, in the RCM Parry Room Library, and 2) a little Ms (perhaps autograph) of Ayleward keyboard pieces at Lambeth Palace library. I don’t remember that they are related but of course they may be. I don’t know how long the Lambeth volume has been there. The RCM may have other Taphouse items …

I haven’t seen these books since I consulted them, 1) c. 1971, temp. Watkins Shaw and 2) c. 1980.

As neither of these establishments features in the chunk above, I hope this info may be new and of some use … Blaise Compton

Yes – I own that Shudi-Broadwood. Where do I start? I bought it at auction at Sothebys about a decade ago. It had been shipped from Perth (Australia) to London – and then to me at BWI airport in Baltimore! FAG Ouseley scratched his name on the case after it was given to him by Fowler Broadwood around 1860. Taphouse made a more-than-respectable profit on it when he sold it. The 1683 Haward, the earliest dated English spinet, is now in Scotland. It has Taphouse’s name in it. In my forthcoming thesis on the English Wing spinet, I will describe it and have a number of pictures. If you’d like me to phone you, please give me your number.