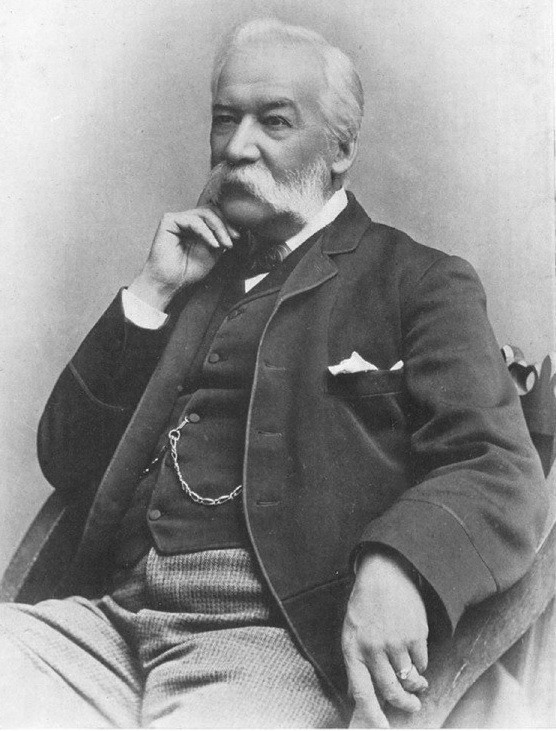

T.W. Taphouse, “a special [photographic] portrait, true to life” from the Musical Times, October 1904

The funeral of Thomas William Taphouse (1838–1905), Mayor of Oxford, which took place “amid many manifestations of sorrow”, was reported in the Court Circular of The Times as “a very large and representative gathering”, attended by several MPs, along with five presidents of Oxford Colleges and all the members of Oxford’s town council. “The procession was of great length … and there was a general closing of shops while the funeral was taking place. So numerous were the floral tributes that they were conveyed in a special [extra] carriage.”

The obituary in the Musical Times spoke of a genial, modest, kind-hearted man, and it’s clear that Taphouse was, by all accounts, a jolly good fellow, and a friend to many, and that he would be sorely missed (not least by the editorial staff of the MT, with whom he had, apparently, regularly collaborated).

Taphouse left school at the age of 14 and was apprenticed to his father, who was a cabinet-maker and furniture-broker. Four years later he left for London to learn the “science of piano-tuning”. On 4 April 1857, he established a music shop, with his father at 10 Broad Street, Oxford. Following a major fire, the business moved to 3 Magdalen Street in September 1858, and C. Taphouse & Son Ltd. was to remain at these premises for the next 124 years.

Described in the census simply as a piano-tuner, Taphouse spent the next 30 years travelling around Oxford with a pony and trap, but he was to become a very wealthy man during this period. For whatever reason, he did not begin his career in local politics until the age of 50, and was elected mayor of Oxford in 1904.

Although his municipal endeavours, particularly those relating to buildings and art works, were mentioned by the Public Orator when he was awarded an honorary MA from Oxford University, also in 1904, it was largely for his “research into old English music” and his discovery of several unknown works, not least Purcell’s “The Queens Funerall March sounded before her Chariot [sic]” and the “Canzona, as it was sounded in the Abbey after the Anthem”, a now famous piece written for the funeral of Queen Mary in 1695.

This was the first time ever that the award – a distinction “as unique as it was deserved” – had been conferred on a tradesman of the city, and it also recognised his “large-hearted unselfishness”, as “he always delighted to place his wide knowledge … , experience and the treasures of his library at the disposal of [others] …”

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

“One of the finest music libraries in the country”

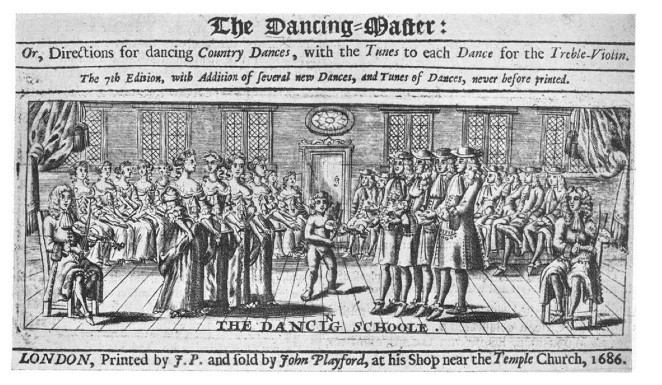

Taphouse’s first purchases took place in 1858 (when he was just 20), when he bought the third edition of Playford’s Dancing Master, in Bath, for sixpence, Morley’s Plaine and Easie Introduction (1597) for 15 shillings, and Mace’s Musick’s Monument (1676), with the portrait, for 25 shillings.

By the time of his death he had amassed more than 2,000 volumes; but many items were sold in unspecified mixed lots and “bundles” at a two-day Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge’s auction in July 1905, so the exact content of his library is not known. There were 876 lots, which made a total of £1062.

Collecting obsolete instruments and old music books is certainly an unlikely hobby for a young man, and why he embarked on it is unknown. In an interview, just a few months before his death, he said that he was “encouraged” in his “hobby” by several eminent collectors of the day, including the composer and organist, Sir John Stainer, who was also Heather Professor of Music at Oxford; noted Bach expert, Sir Walter Parratt, who became Queen Victoria’s Master of the Queen’s Musick in 1893; and Sir Frederick Ouseley, whose own library (now in the Bodleian, Oxford) contained Handel’s conducting score from the Dublin premiere of Messiah.

Described by Alex Hyatt King as “ that enterprising collector”, Taphouse combined discernment, the broad knowledge of a self-taught expert, very wide interests (with a penchant for 18th-century and earlier items), and significant financial resources.

He was particularly keen on Purcell and owned around 20 items, including the very rare Sonnata’s [sic] of III Parts (his first publication); Diocletian [sic] 1691, The Tempest; and a large manuscript collection, lost and only recently found (see Holman in Early Music vol. 40, no. 3), containing the unique copy of the so-called “Violin Sonata in G minor” Z780.

There was also a lot of Playford, often in multiple editions, including The Division Violist (1659), sold for £2. 6 shillings; Introduction to the Skill of Musick (1664); Musick’s Delight for the Cittern (1674); Harmonia Sacra (1688); and Simpson’s Compendium of Practical Musick in 5 Parts, together with Lessons for the Viols (1677).

There was also a lot of Playford, often in multiple editions, including The Division Violist (1659), sold for £2. 6 shillings; Introduction to the Skill of Musick (1664); Musick’s Delight for the Cittern (1674); Harmonia Sacra (1688); and Simpson’s Compendium of Practical Musick in 5 Parts, together with Lessons for the Viols (1677).

Taphouse had a small but important collection of early editions of madrigals: Thomas Morley’s Madrigalls to Foure Voyces, The First Booke (1594); the part-books of his Canzonets, second edition (1606), sold for £21. 10; John Bennet — Madrigalls to foure voyces newly published … his first works (1599); and Thomas Weelkes – Madrigals of 5 and 6 parts, apt for the Viols and voices (1600) and Ayeres or Phantasticke Spirites for three voices (1608). From the same period, he owned a copy of the very rare Briefe Introduction to the Skill of Song (1596) by William Bathe.

Books on history, biography and travels accounted for a total of 343 volumes; church-music-related items and psalmody numbered 129. The collection was also rich in early theory, with 98 volumes, including Nemorarius – In hoc opere contenta … (1496), the first treatise on mathematics in music; Chas. Butler’s Principles of Musik in Singing and Setting (1636); and Prattica di musica (1596) by Zacconi.

Lot 582 in the book and music auction, “A Collection of 69 original vocal and instrumental pieces, autograph scores, by S. Bach [presumably J.S.], Benda, Dr Blow, Dragonetti, Palestrina, Scarlatti, S. and C. Wesley and others”, is an example of one of the unspecified lots, which was sold for only £3.

In the end, Leeds Public Libraries bought 143 lots, book dealers snapped up a further 323 lots and known private collectors, such as W.H. Cummings, Frank Kidson, and “Daddy” Mann, of King’s College, Cambridge, bought around 60 lots, leaving 350 lots unaccounted for.

This collection was mentioned in the first edition of Grove, and it is in the current, online version that Taphouse’s library is noted as being “one of the finest”.

The musical instrument collection

At the time of the Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge instrument auction (7 June 1905), the most usable antique keyboard instruments were retained by Taphouse’s harpsichord-playing step-daughter, Nellie Woodward-Taphouse. It’s unknown to what extent other choice items were kept by the family.

The instruments listed in the sale catalogue are rather a hotchpotch, and include six recorders (for details of “that” Bressan, see part 2 of this article), four oboes, a violin and viola (previously owned by the University Music School) made by William Baker of Oxford in 1683, six English citterns, six lutes, three viols (one each from France, Germany and Italy), miscellaneous brass instruments, an early serpent, several bagpipes, mandolins, eleven single and double flageolets and an Epinette des Vosges. Taphouse seems to have bought simply whatever caught his eye, which accounts for the fourteen flutes (German, made of ivory, and in the form of walking sticks) and the eight dancing-master violins that appeared in this sale.

He certainly didn’t have the systematic approach of Canon Francis W. Galpin (1858–1945), whose first collection – started in the 1870s – representing 2,000 years of music-making in 562 items, ended up in the Boston Museum of Fine Art in 1917, as no British institution was interested in acquiring it.

The instrument sale consisted of 125 lots, amounting to 200 items, including 80 non-European instruments, which made a total of £230. 4 shillings.

A further 41 instruments, originally owned by Taphouse – including an old English five-string tenor viol, which was converted to a four-string by a travelling gipsy – are currently housed at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford.

More next time.

If you appreciate this blog post, please share this link //bit.ly/1OhQmyr with your friends.

Copyright © 2015 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

Loved this research … as an instrument maker with similar career bits myself … it is so fine to increase awareness of these fine musical and organological threads. Lovely work!

Thank you for this highly informative and accurate article about one of England’s important 19thC musicological giants. Although it is five years old, I just read it for the first time. Please keep up this level of research and continue to post it. Thanks!