|

|

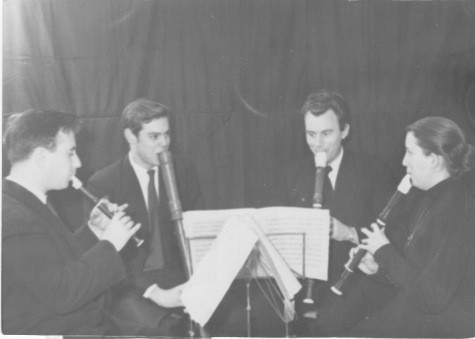

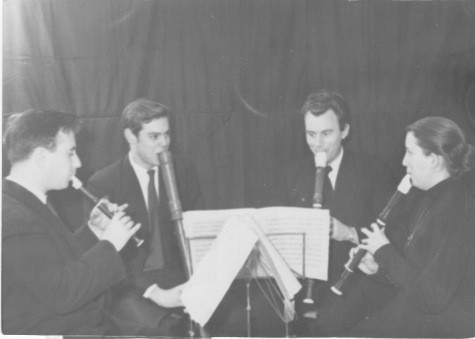

The Leonhardt Consort in 1954. FLTR: Kees Otten, Gustav Leonhardt, Hans Bol and Marie Leonhardt www.semibrevity.com As one of the two main recorder players in Holland after the war (the other was Joannes Collette) and an acknowledged expert on early music, Kees Otten was well known to George Leonhardt (father of Gustav), who was on the Board of the Dutch Bach Society and himself a well-known figure in the musical scene of Amsterdam.

Otten remembers:

When Leonhardt returned to Holland [from Vienna] his father asked me if I would ‘keep an eye’ on his son [i.e. work with him]. This was a bit of a problem, as I already had a harpsichordist, Jaap Spigt, with whom I regularly performed [since 1950]. But when I started to play with Leonhardt, I found his approach very interesting, and we decided to set up an ensemble together [in 1954] which, because of his impending marriage to Marie, became known as the Leonhardt Consort.

We concentrated on late 17th- and early 18th-century music. Leonhardt wanted to do just Concerts royaux in one concert and then just 17th-century German music in another … which was completely unheard of at that time, and we had many debates about this. My view was that we should end each concert with something by Telemann, which the audience would definitely enjoy! My approach was probably more commercial than his, and I also really liked Telemann.

The players

The initial line-up consisted of Leonhardt who, at that stage, was still playing a pedal-powered harpsichord made by Robert Goble, with a 16-foot stop; his violinist wife, Marie; Kees Otten and the cellist and gamba-player Hans Bol, with whom Leonhardt (and Joannes Collette) had played gamba trios in radio programmes, as part of series devised and introduced by Otten.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

Otten’s new wife, Marijke Ferguson, was also mentioned as being a member of the new baroque music group, in a newspaper article (about Kees Otten and the recorder) in which the advent of the Consort was announced in May 1954. She told me, however, that she only ever played the second recorder part in John Blow’s Ode on the Death of Henry Purcell, in the concerts given with Alfred Deller; see the photo below.

Bol’s involvement was apparently short lived and Dijck Koster quickly replaced him as cellist. She was a conservatory friend of Marijke Ferguson and Antoinette van den Hombergh (who later joined the Consort, and played the medieval fiddle in Otten’s group, Muziekkring Obrecht). All three of them had previously lived together in a house on the Prinsengracht in Amsterdam, which was reserved for single young ladies.

The violinist Jaap Schröder (who was a member of the Netherlands String Quartet and, at the same time, the concertmaster of the Dutch Radio Philharmonic Orchestra) also occasionally played with the Consort, as well as working with Kees Otten in other formations, particularly for the radio.

The concerts

FLTR: Kees Otten, Marijke Ferguson, Alfred Deller, Dijck Koster, Gustav & Marie Leonhardt (1956) www.semibrevity.com I’ve been unable to find information about any radio broadcasts made by the first incarnation of the Leonhardt Consort; but I have seen printed programmes from seven concerts which they gave together. It’s difficult to know whether and to what extent they are representative.

They all include a combination of solo sonatas, trio sonatas and harpsichord solos. Between 1954 and 1957, the same pieces regularly appear on programmes given in various small-scale venues, like museums, galleries and castles. Froberger’s Lamentation on the death of Ferdinand III appears four times. The other most popular works come from Frescobaldi, Bach, Johannes Ghro, Samuel Scheidt, Charles Dieupart, Purcell, John Coperario, Domenico Scarlatti, Francesco Turini, Matthias Weckmann, Biber and, surprisingly, given Leonhardt’s aversion to him, Handel. In addition, single works by 14 other composers appear. All the programmes are very varied, with the exception of two concerts given with Alfred Deller, where Purcell and English lute-song composers dominate. In only one instance is there a piece by Telemann, and it does come at the end of the evening.

Leonhardt, speaking of his adventurous repertoire choice in the 1950s, recalls:

Most of it was completely unknown – much of the music we played was what I had brought back from Vienna … We didn’t give many concerts, because the public for such repertoire was still quite small.

About Alfred Deller

Kees Otten was impressed with Deller, whom he met in 1956, but also found him irritating:

Leonhardt also brought us into contact with Alfred Deller, whom he hugely admired … and for us this way of singing was something completely new.

Apart from being very interesting, Deller was also unbelievably lazy. During a rehearsal he only wanted to go through the first few bars of a piece and would then lie down. He would just look at possible difficulties [in the music] and would say, “I don’t know exactly what I’ll do”, and that was certainly the case, as he did something different every time. He more or less improvised half the time, sometimes faster, sometimes slower, just depending on how he felt. We [the Consort] just followed whatever he did.

Leonhardt’s comment is more generous:

I won’t say he was one of the greatest singers, but he was certainly one of the greatest singing artists. That is what makes him unforgettable… It was his diction and ability to convey words that was unsurpassed. His presence was extraordinary and, although the records can be marvellous, they do not really give an idea of what he was like in concert. Working with Deller was certainly one of my most memorable experiences.

(See the blog post on the first recording of Deller, Harnoncourt and Leonhardt here)

During the period when he was involved with Leonhardt, Otten’s more popularising and varied approach led to him giving many more concerts, including around 100 in schools.

If you have any information, concert programs, bootleg recordings or anything else relating to the Leonhardt Consort, or could suggest other people or possible sources, please get in touch by using the Comments Box below. Your reply will not appear on the blog.

However, quite apart from artistic differences, there simply wasn’t much music written for the Consort’s initial combination of harpsichord with one or two recorders and two strings, except for some works by Handel, Telemann and Scheidt. So, the Ottens left the Leonhardt Consort in 1957, and it continued as an ensemble of strings and harpsichord, for which there was, of course, a great deal of repertoire.

In fact, this second, string-band version of the Consort had already started to give concerts in 1956, as Leonhardt had begun the previous year to recruit and train more string players, and provide them with historical instruments and baroque bows.

More on this another time.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Marijke Ferguson, Marina Klunder (Kees Otten’s widow), Jaap Schröder and to Jolande van der Klis for her excellent Oude muziek in Nederland which has been a valuable source in writing this post. The English translations of various quotes are my own.

© Semibrevity 2014 – All rights reserved

Also of interest:

Kees Otten, Dutch recorder pioneer

Muziekkring Obrecht – the first ever Dutch ensemble for medieval & Renaissance music

Frans Brüggen: the early years (1942–1959), with his teacher Kees Otten

Gustav Leonhardt & Martin Skowroneck – Making harpsichord history

![Malcolm-George-02[1965]](//www.semibrevity.com/wp-content/uploads/Malcolm-George-021965.jpg) George Malcolm in 1965 Guest blogger: David Lord, composer and record producer

I had the privilege and pleasure of knowing George Malcolm for over 30 years, having first met him at the Spode House Easter Music Week in 1966. I was then a young student at the Royal Academy of Music and was thrilled to meet the dedicatee of Benjamin Britten’s brilliant Missa Brevis, the piece that, when I first heard it as a schoolboy, spurred me to try my own hand at composition.

I had no idea that George would become an inspirational mentor and the most generous and loyal of friends. Through him I would meet many eminent musicians and was introduced to the vibrant musical life of London and festivals like Aldeburgh, Dartington and Bath.

With the help and support of George’s executor, Christopher Hirons, I’ve put together a website in memory of this great musician [who was a pianist, harpsichordist, organist, choirmaster, orchestral conductor and composer]. The site includes much fascinating archive material, reviews, interviews, pictures, anecdotes and reminiscences, as well as many audio and video clips.

George’s musical talent was spotted very early, and after 18 months of piano lessons with a gifted nun in the kindergarten, he started to study with Kathleen McQuitty FRCM at the Royal College of Music, aged seven [and remained the only child there for several years].

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

Following Oxford University, he returned to the RCM and studied with Herbert Fryer, intending to become a pianist. The War drastically changed the direction of Malcolm’s life, and he was appointed a RAF bandleader, organising and conducting concerts all over the country.

On being demobbed he planned to resume his career. Taken with the idea of owning an antique instrument, for his own pleasure at home, he bought his first harpsichord at an auction [in 1946], with his demob gratuity. Such an instrument was rare then, and very soon they were both in great demand.

[This first harpsichord was a two-manual Shudi-Broadwood, built in 1775 (similar to one owned by Mary Potts), which Malcolm sold in 1958 to Leonhardt’s first Amsterdam student, Lenie van der Lee. Malcolm always preferred to play “revival” instruments made by either Thomas Goff or Robert Goble, as mentioned in this 1973 interview.]

According to the guitarist and lutenist Julian Bream,

… there was nobody like George Malcolm on the harpsichord, I mean, he played with such verve, with such vigour, and with such inventiveness …

Throughout his life George Malcolm championed the harpsichord through concerts and recordings, mostly drawing on the large 18th-century keyboard repertoire. He was also a fine exponent of more recent works and made some brilliant arrangements himself.

George was appointed Director of Music at Westminster Cathedral in 1949. He had a deep affinity with Catholic church music, and achieved great success in producing the bright “continental” sound that so impressed Britten when he wrote his Missa Brevis especially for the Cathedral Choir.

By 1959 ever-increasing demands for concert performances caused Malcolm to resign his post at the cathedral and become conductor of the Philomusica of London [Thurston Dart’s old band] as well as associate conductor of the BBC Scottish Orchestra.

The pianist Andras Schiff, who knew Malcolm from an early age and recorded piano duets with him, on Mozart’s own Walter fortepiano, had this to say about him:

George Malcolm was a great musician, a Renaissance man, a wonderful human being. He has been influential in the development of choral and instrumental music in Britain and abroad, and l consider myself one of the fortunate recipients of his immense knowledge, broad culture, and excellent taste. He should never be forgotten.

Mr Lord would welcome any further information about George Malcolm, and can be contacted through the website.

© David Lord; Semibrevity 2014

Free performance material for George Malcolm’s “Variations on a Theme of Mozart” for four harpsichords

David Lord writes (October 2015):

David Hansell has prepared a score and parts, from the autograph manuscript, of George Malcolm’s brilliant pastiche “Variations on a Theme of Mozart” for four harpsichords (or pianos), which he wrote for Thom Goff’s annual harpsichord jamboree at the Royal Festival Hall. David, and the copyright holder Christopher Hirons, have generously made this material freely available here for download and performance. With the centenary of George’s birth coming up in 2017, it is hoped that we may get a performance or two, though the logistics of getting four harpsichords together are perhaps somewhat daunting!

The Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble in 1954, with Frans Brüggen on bass www.semibrevity.com When Frans Brüggen (born 1934), the youngest of nine children, was about 6 years old, he got his first recorder lessons from his brother Hans. It was their mother’s idea, as the schools were often closed because of the war, and Frans began to “mess around” out of sheer boredom, “which my mother couldn’t deal with, on top of everything else.”

Frans Brüggen: “Learning the recorder was an excellent idea, I immediately fell in love with that instrument and tootled my way through the rest of the war years.”

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

As well as studying law, his older brother, Hans Brüggen, was a talented oboist who knew Hans Brandts Buys (see also here) and sometimes played in his performances of Bach cantatas. It was through these concerts that Kees Otten knew Hans Brüggen (and also another musical brother, the violinist Albert, father of Daniël Brüggen of the, now defunct, Loeki Stardust Quartet), and that’s how Kees came to meet Frans, when he was around 8 or 9 years old and still in short trousers.

He could blow the stars out of the sky

Otten remembered the occasion vividly: “He was very small, but he could blow the stars out of the sky, even though he didn’t sometimes feel like playing the recorder at all.”

When Hans couldn’t teach his little brother anything more, Kees Otten began to give him regular lessons, and they played together in recorder quartets in a house-concert in 1948, when Brüggen was just 14.

Asked by Brüggen’s father whether he should allow Frans to make the recorder his career, Otten recommended against it, saying that you shouldn’t become a musician unless you were 100% committed to doing so. “Happily,” he admitted later, “Frans didn’t take my advice.”

Kees gave very good lessons

Subsequently, Brüggen studied formally with Otten at the Amsterdam Muzieklyceum and, in 1954, was only the second person in Holland to pass the new recorder exams.

“Kees gave very good lessons,” Brüggen has said, “and his approach had a good effect on me, but straight away I wanted to be better than him. Shortly after I passed my exams I stopped seeing him completely. That’s how these things go: with help from a teacher you reach a point which enables you to continue studying by yourself, so that you find your own musical way. For me, that was really necessary, as I wanted to do everything very differently. Playing in ensembles was alright, but more than anything I wanted to be a soloist.”

Brüggen had played, for a while, in Otten’s Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble (see also here) and, according to Otten’s incomplete archive, had been involved in around a dozen radio broadcasts (some of which were part of the significant series in which Otten seemed to specialize) plus five or six live concerts. Brüggen, who has large hands, often ended up with the bass recorder which, according to Marijke Ferguson, he hugely enjoyed and played with great verve.

Auntie Janny

Brüggen’s different attitude was evident when, in 1954, during his debut radio broadcast with Janny van Wering (1909 – 2005), Holland’s most respected harpsichordist at the time, he refused to ornament the slow movement in the way he had been taught by Otten.

“I really dug my heels in,” he said, “as I believed that playing ornaments was often used to cover up a poor technique, and the more you played ornaments, the worse you were at playing the recorder. And I wanted to demonstrate how well I could play.”

Janny van Wering, who, despite dispelling the doubts that her student, Jaap Spijgt, had had about playing with Kees Otten (see this blog post), admitted that she had not taken the recorder very seriously herself before playing with Brüggen. For her, it summoned up the spirit of the Socialist Workers’ Youth Movement (the AJC), which promoted physical exercise, folk dancing and amateur music-making – mostly on recorders – as a means of developing and educating young people.

However, she described the recording session in 1954 as “a revelation”, so much so that, after the broadcast, she offered to play with Brüggen again, and they subsequently performed a great deal together.

In the late 1950s they gave a series of 15 or 20 school concerts with the violinist Jaap Schröder (with whom they made a record of Telemann Trio Sonatas in 1958). In the course of that year, Schröder and Brüggen travelled around Holland together in Brüggen’s small Fiat car, with Van Wering, and her harpsichord, being transported separately.

Although Brüggen often played with Gustav Leonhardt, his collaboration with van Wering continued until at least 1963, when they gave a concert together in the Amsterdam Concertgebouw in May and a radio broadcast for the BBC’s Third Programme in September.

In 1955, at the age of 21, Brüggen was appointed professor at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague. He was later also to teach at his old school, the Amsterdam Muzieklyceum.

It’s curious now to reflect on what Brüggen said about the music he played at that time:

In the 1950s, we didn’t think of the recorder as an “early music” instrument, and we had absolutely no historical awareness. I just played what I felt like, which included, for better or for worse, [tunes from] symphonies by Tchaikovsky and Beethoven. I also played Handel sonatas, but that was because of the recorder, not because of Handel.

It was only when Brüggen came in contact with Gustav Leonhardt (see a translation of Brüggen’s 1971 interview about Leonhardt) that the connection between early musical instruments and the music itself became apparent, as he remarked:

There was a considerable difference between Leonhardt and me: he really knew [how to play early music] and I just had some ideas. Through his education in Basel and his experiences in Vienna [at libraries and playing with the Harnoncourts, among others], he had a much better knowledge of musical styles and he knew how to apply it to his playing. He could tell you exactly [from his research] why you should play a piece or a phrase in a particular way: he wasn’t guessing … With the awareness that “early music” was something completely different, I began a new phase in my career. Then, I had to know everything about it, all at once, and I read a great deal [about historical performance practice] and followed all the instructions to the letter.

Thanks are due to Marijke Ferguson, Marina Klunder (Kees Otten’s widow), Jaap Schröder and to Jolande van der Klis for her excellent Oude muziek in Nederland which has been a valuable source in writing this post. The English translations of various quotes are my own.

If you appreciate this article, please share the link with your friends.

© Semibrevity 2014, All rights reserved.

Guest blogger: Donald Gill

Donald Gill (2nd from left) with Michael Schaeffer, Michael Lowe and Anthony Rooley at a Lute Society Summer School in 1976

Apart from making instruments such as the Renaissance guitar, vihuela, cittern, orpharion, French mandore, viola de mano and bandora (including one for James Tyler), and playing all of the above, Mr Gill also wrote two small books and contributed a number of authoritative articles to the Galpin Society Journal, the Lute Society Journal and Grove.

The following piece was written in November 2012.

I was very appreciative of the birthday greetings in Lute News 103 [October 2012], though I did not recognize myself as one of the ‘great pioneers’ of the lute revival.

As apparently I am now the oldest member of the Lute Society, I feel that some of my memories should be recorded, but I would have to go back more than the 56 years since the Society was founded for them to mean much.

I therefore go back to around 1931–2, when my best friend at school bought a ukulele, which meant that I had to have one too. My musical activities at that time involved piano lessons, and later, playing the viola in the school orchestra, with no great enthusiasm for either. But when the daughters of a family we were on close friendly terms with, whose father was German, heard of the ukulele they straight away said, ‘Oh, you must get a guitar!’

In those days, nobody knew what a guitar was, except as something vaguely Spanish, but they were familiar to Germans. Somehow I scraped together about 15 shillings [currently equivalent to 75p!] and bought a guitar in a local junk shop, and a copy of the Carulli Tutor, and set about teaching myself.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

I heard the occasional recital by Segovia on the radio, and was very impressed by the vihuela pieces that he played, and this started me off wanting to know more about the vihuela and its history. This led inevitably to the lute, as I had also heard Diana Poulton play on the radio, and started searching for books about the lute, such as they were in those days.

Eventually I acquired an old German lute-guitar from a junk shop in Charing Cross Road, chopped its peg-box off and fitted a reflexed alternative to make it more lute-like and allow for double strings.

Lute music was a problem, as none was published in the UK and, in any case, the war came along and interrupted further progress, which had to wait till I got back to Britain in 1948 and began to pick up the threads.

These included contacts with other early investigators who were generous with information and sources of music. I was fortunate to be posted to a London job in 1949, and met Diana Poulton, Ian Harwood and Major Michael Prynne [read Mr Gill’s tribute to him in the 1979 Early Music].

I managed to get together £35 for one of the lutes that Alec Hodson was making – a copy of the ‘Warwick’ Frei. [The famous early 16th century instrument by Hans Frei in Warwick County Museum is arguably one of the finest of all surviving lutes.]

Renaissance lute, labelled Alec Hodson, Maker, Lavenham, Suffolk 1949 Research was interrupted by two short-notice three-year [army] postings to Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong in 1951–4 and 1956–9, so I was actually in Singapore when I became a member of our Lute Society. I was again fortunate that from 1954–6 I was in a London posting and could resume research, acquiring music, attending meetings in London, and copying British Museum Library sources.

My time in Singapore convinced me that lutes would not survive such heat and humidity, and I thought that the orpharion or bandore should be investigated — metal strings and simpler construction — if I was going to be able to enjoy plucking in possible future postings.

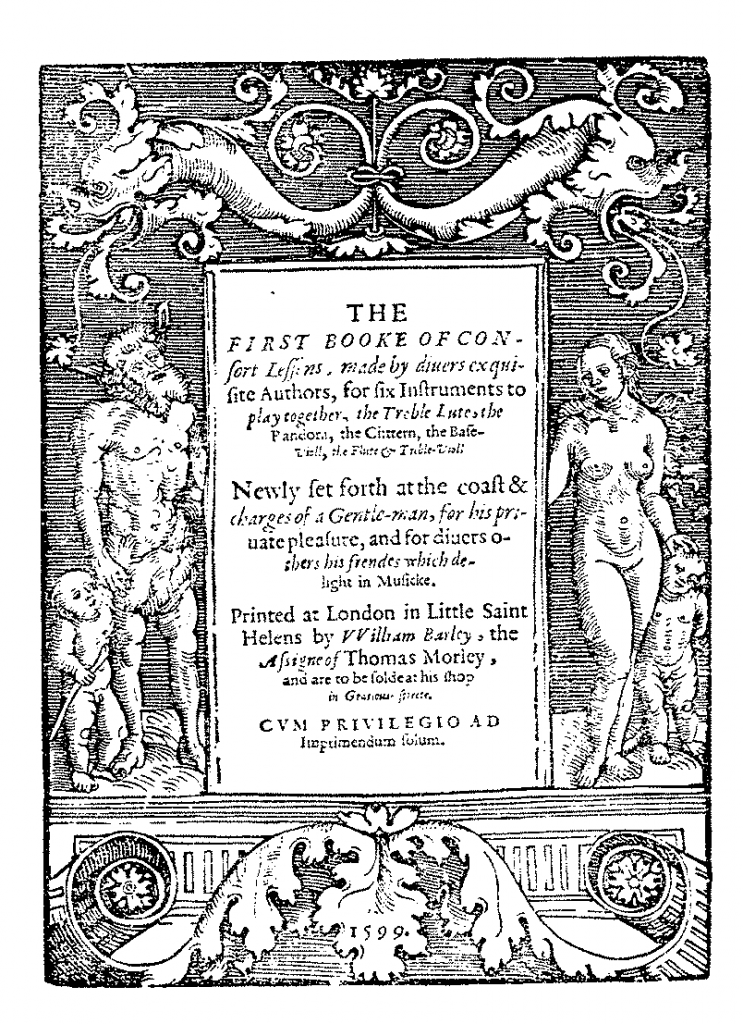

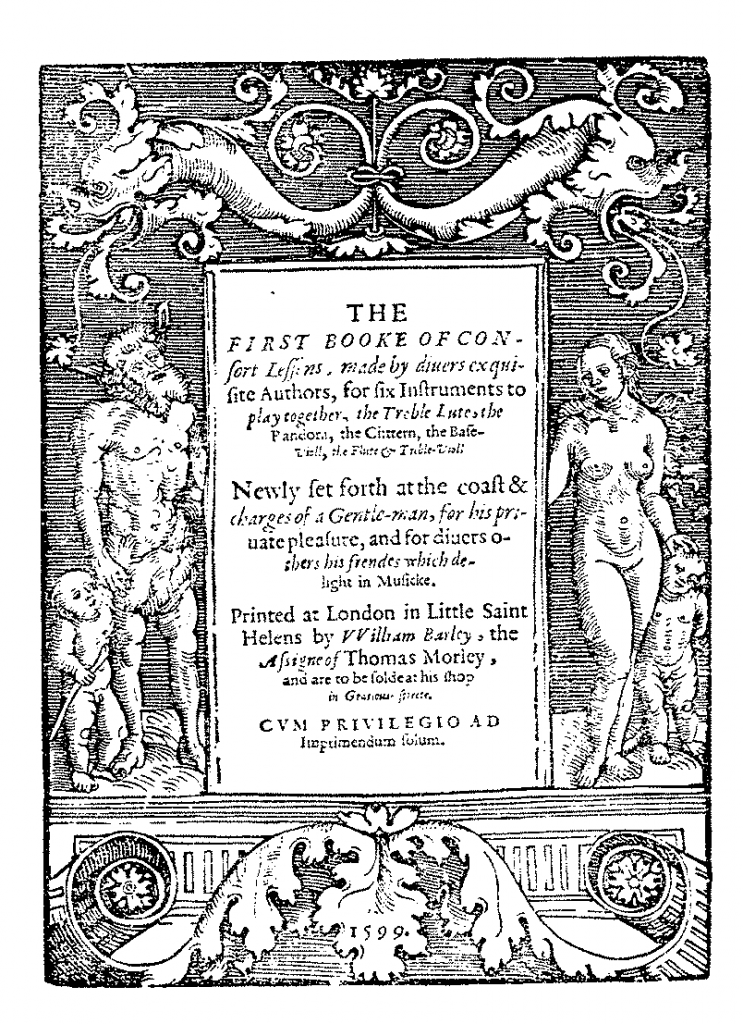

About this time the Morley Consort Lessons were published, which became an added incentive.

Title page of Morley’s The First Booke of Consort Lessons 1599

[Thomas Morley’s The First Booke of Consort Lessons (1599 & 1611) was arranged for the distinctively English broken consort or ‘consort-of-six’, consisting of three plucked string instruments (lute, cittern, and bandora – called ‘Pandora’ by Morley), two bowed instruments (treble viol or violin and bass viol), and a recorder or transverse flute. This special combination of instruments was reportedly a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I.]

One thing led to another. I found myself wanting to find out about the early guitar as well as the vihuela, and then the small lutes, French and Italian mandores and mandolinos also seemed worth investigating.

This led to curiosity about the big mandoras and gallichons [or gallichones], which struck me as being an excellent alternative to lutes for the technically challenged (such as myself) as well as being a significant part of the whole picture. This coincided with Martyn Hodgson’s independently reporting on the restoration of an example in the Castle Museum, York, and his identification of it as a mandora or gallichon.

I always wanted to know what the music sounded like, and not being a millionaire I made my own sample instruments, starting with a bandora and going on to other instruments such as 4- and 5-course guitars, mandores, mandolinos, and a bell-gittern. Also a couple of vihuelas and a viola da mano, as research progressed.

After leaving the army, and then ten years in Northern Ireland, where some research was possible but an absence of colleagues and meetings was felt, we moved back to England in 1974. I have however been thwarted recently by arthritis and can no longer make or play. If that had not been the case I would have been looking at the guitar and kindred late citterns now, to help fill in the picture.

My memories are more diffuse than specific and are very much coloured by the good nature and generous helpfulness that seems to be characteristic of Lute Society members and helped make our Summer Schools so enjoyable.

There is, however, one specific memory that has stayed clearly with me. One evening I took Major (later Major-General) Michael Prynne in my 1923 Vauxhall open tourer to visit Diana Poulton at her country cottage. The thought of two regular army officers, one a vintage sports car enthusiast, visiting the doyenne of British lutenists, still appeals to my fondness for the unexpected. And the visit itself was a great pleasure, made completely unforgettable by the weather, which was cloudless and warm, with a full moon giving so much light that headlamps were hardly needed. I don’t know what Major Prynne thought of motoring with the hood down, but to me, a long-time member of the Vintage Sports Car Club, it was perfection.

© Donald Gill 2014

Thanks are due to the Lute Society for the photo at the top, to Lute News magazine, where this article was first published, and to Gardiner Houlgate for permission to reproduce the photo of the Alec Hodson lute, which appeared in one of their frequent musical instrument auctions.

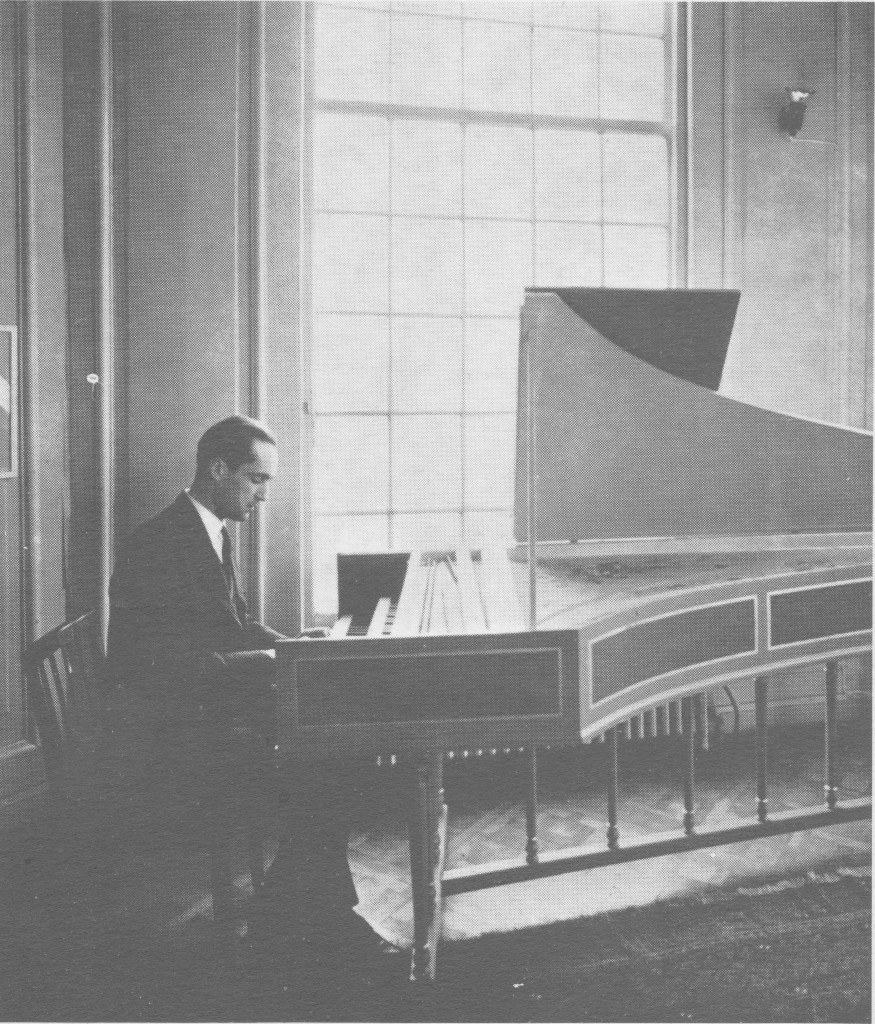

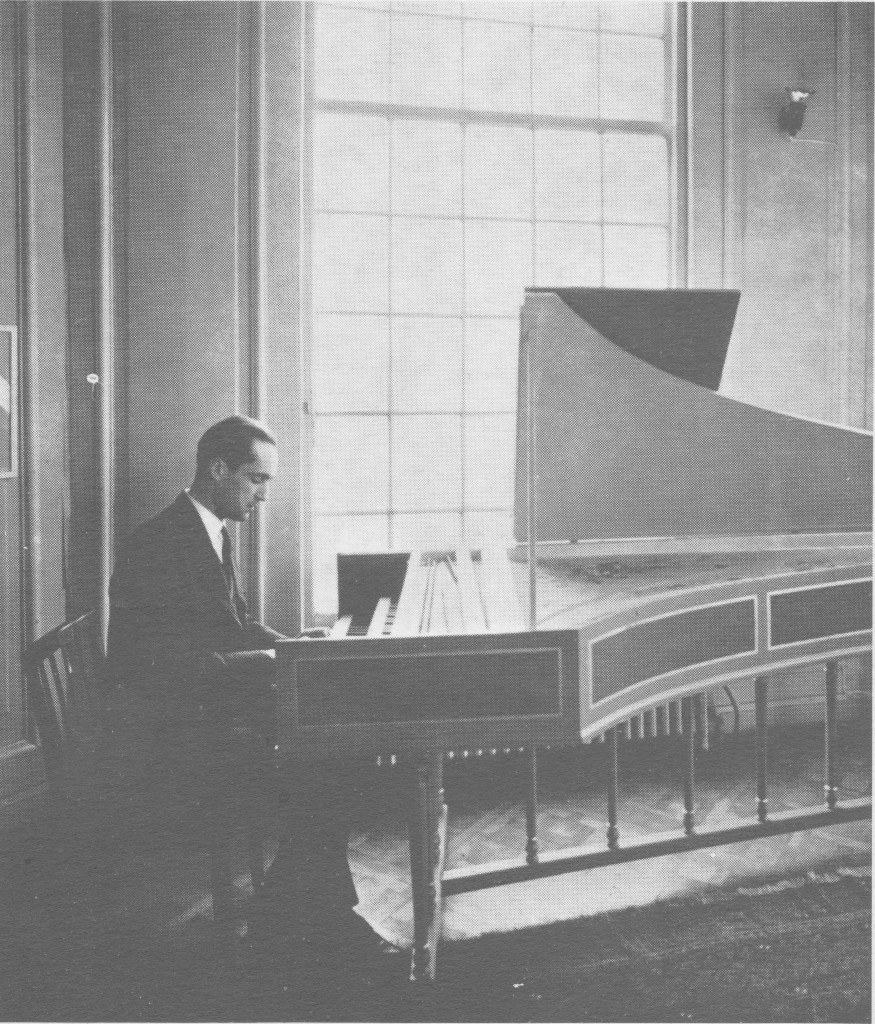

Gustav Leonhardt (c. 1965) at the Dulcken made by Martin Skowroneck www.semibrevity.com Martin Skowroneck has joked that if he could have afforded to buy a Dolmetsch recorder in 1948 or 1949, when he was a student flute teacher in Bremen, then perhaps he wouldn’t have started making musical instruments at all.

As it was, he was dissatisfied with the German-fingering “chair leg” recorders which were the only ones available to him, and determined to try to make something better, using a lathe cobbled together from US army surplus parts, which came with a stock of wood consisting of a bundle of maple baseball bats. That he was successful is evidenced by the fact that he was asked to make instruments for others, including a Hotteterre transverse flute (from the Berlin Musical Instrument Museum’s collection) for Professor Gustav Scheck, who played in the then-famous trio with harpsichordist Fritz Neumeyer and pioneer gamba-player August Wenzinger, who was also head of Schola Cantorum Basiliensis.

Skowroneck continued making flutes and recorders – initially from the baseball bats – until the early 1990s.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

Skowroneck’s first keyboards

In 1952 Skowroneck was asked to restore a Merzdorf clavichord, made in the 1930s, that had been badly damaged in the war; this led him to build two clavichords based on this instrument – one for himself and one for his sister – which he quickly discovered “had never existed in former times” (i.e. the 17th or 18th centuries). After two more clavichords, he built his first harpsichord in 1953.

Following a concert by the Scheck–Neumeyer–Wenzinger trio which “stirred me up thoroughly”, he had decided that if he was only ever going to build one harpsichord, then it should be a big one.

To get an idea of why they made such an impact on Skowroneck, here’s a sound clip from a recording made in November 1950, at low pitch, of Gustav Scheck, playing a transverse flute made by F.G.A. Kirst in Potsdam c. 1750, with Emil Seiler on a viola d’amore by Lupo, August Wenzinger on a 1657 Stainer viola da gamba and Fritz Neumeyer playing a Neupert harpsichord, “specially constructed to specifications by [Johann] Heinrich Silbermann”, in part of the final Allegro from

Skowroneck’s first attempt was a two-manual instrument with four sets of strings, including a 16–foot stop, based on the Berlin Musical Instrument Museum’s No. 316 (the so called “Bach-Harpsichord”) with elements of the museum’s No.5, probably by Gottfried Silbermann. This early Skowroneck is now also on display in the museum.

The Berlin Musical Instrument Museum was a key resource for Skowroneck in those early years. In his book Cembalobau/ Harpsichord Construction (in German and English), he writes about the kindness of the museum’s curator, Dr Alfred Berner, who gave him unlimited access, throughout the week, to handle and measure instruments, although the museum was then only officially open for two hours on a Saturday, for guided tours. This was effectively where Skowroneck learned the craft of making musical instruments based on historical examples. As Gustav Leonhardt later commented, “it could not be otherwise, because these are the only available teachers.”

A fateful weekend

In 1956, it was Dutch recorder pioneer Kees Otten who took Leonhardt, in a borrowed car, on a fateful road trip to Germany. In an interview given in 1974, Leonhardt recalled:

Hearing antique instruments in Vienna in the museum, and playing them – also in England – those belonging to Raymond Russell, for instance – made me realise that modern harpsichords were impossible. Then one day Kees Otten had heard of a wonderful flute maker named Martin Skowroneck, in Bremen. By chance we both had a free weekend and decided to drive there together to see him. At Skowroneck’s place I noticed there was a harpsichord in the room, as well as all the flutes — it was a revelation to me …

The instrument concerned was Skowroneck’s harpsichord No.5, built in 1955, in which he used a Ruckers construction, for the first time, with a correct soundboard layout. He says in his book, “The resulting sound gave me an important impetus [as] in spite of the backpost construction, it resembled an historical instrument.”

Although impressed, Leonhardt did not order an instrument for himself. Instead, he recommended Martin Skowroneck to the Harnoncourts, in Vienna, who were trying to find a harpsichord as lightly constructed as the historical stringed instruments they were playing in Concentus Musicus, which had just been founded in 1953.

As no plans or drawings were available, and few people had ever seen the inside of an old instrument, Skowroneck had some reservations about making a thin-walled, lightly braced Italian harpsichord, but was persuaded to attempt it by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who agreed to assume any financial risk should the structural integrity of the instrument fail.

In 1957 Skowroneck completed his No. 7: a one-manual harpsichord “after an Italian instrument of 1700”. This was his first truly historical harpsichord, and it can be heard in many of the recordings of Concentus Musicus from the 1960s and early 1970s. The initial disposition of 8′ 8′ 4′ was, however, not typical for the style and the 4′ register was later removed.

The 1957 Skowroneck, “after an Italian instrument of 1700″ www.semibrevity.com In the course of the next five years, Skowroneck built ten more Italian harpsichords, including a small, easy-to-carry version for Leonhardt in 1960. He also made twelve clavichords of various kinds and a two-manual Flemish harpsichord in 1961 which, although it has been used in recordings, has always stayed in the family.

A “quasi-Dulcken” for Leonhardt

In 1962, Leonhardt asked Skowroneck to make him an instrument based on two 2-manual harpsichords, by Joannes Daniel Dulcken, both built in 1745, belonging to museums in Washington and Vienna. Skowroneck also referred to the work of Dulcken’s contemporaries, particularly Joannes Petrus Bull, who had been his apprentice. The originals were built very much in the Flemish tradition of the Ruckers family, extended to a fully chromatic five-octave compass, and were 2.60 meters long.

Skowroneck describes below the information that he had to work with:

I had a few freehand sketches with measurements of the Dulcken harpsichord [in the Smithsonian Institute] in Washington [from Leonhardt] and some measurements of the Dulcken in Vienna [in the Kunsthistoriches Museum]. My little sketch contained some details of the inner construction, but I had no idea about the typical double case of the Dulcken. In Washington the double wall on the inside had erroneously been removed as not being original. This is only an indication of how little we knew at that time …

Some details of the original did not convince me, and I altered them. For instance, for my taste, the 8′ bridge was a little too close to the bentside in both the instruments. So I altered the form of the case somewhat. The result was, as I had to repeat far too often, an instrument close to Dulcken, but far from a copy.

Leonhardt’s “quasi-Dulcken” followed the original disposition of 8′ 8′ 4′ Nasal 8′, plus a buff stop, but was lighter, and had a completely different inner construction from the original (the photo on p. 139 of Cembalobau shows just how different it was). In total, Skowroneck made four Dulckens and it went on to become one of the most famous, and most copied, instruments in recent harpsichord history.

The theme of re-creating historically plausible instruments, but not producing faithful copies, is very important to Skowroneck, and it permeates all the design and building principles outlined in his Cembalobau.

The single exception to his normal way of working is the 1755 fake Lefebvre harpsichord – which Skowroneck made for a bet with Leonhardt. Actually, this is his best documented instrument, as he himself wrote a very detailed article about its construction in the 2002 Galpin Society Journal.

Other opinions

Given that the first harpsichord kits made by piano-technician-turned-harpsichord-maker, Wolfgang Zuckermann, had no bentsides and were made of plywood, it’s curious that in his book, The Modern Harpsichord, written in 1969, he reveals his taste for authenticity. He writes warmly about Skowroneck’s instruments which “have flute-like (not silvery) trebles, reedy (not rustling) tenors, and sonorous (not booming) basses [as compared with German factory-made instruments of the time].”

According to Zuckermann, a Skowroneck harpsichord “does what the player, the listener and the music want it to do … it neither resists nor encourages its user, but mirrors precisely his own strengths and weaknesses … a characteristic which was also found in the Ruckers instruments of old.”

Much more recently, in September 2013, the eminent American harpsichord builder, John Phillips, said in an interview that “Skowroneck [was] one of my idols … I encountered some of his instruments early on, and they were different from anything I had heard before. They never overwhelmed you with sheer beauty of sound. They were players’ instruments, a tool for genuine music-making …”

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Tilman Skowroneck, and to his parents, for permission to use their copyright material and also for assembling information specially for this blog post.

Sad news, received since this blog post was published

Martin Skowroneck passed away on 14 May 2014, at the age of 87.

Martin Skowroneck was making harpsichords till the very end of his life. He always worked alone, and no doubt subscribed to the view of Johann Ludwig Dulcken (J.D.D.’s grandson) – which he once mentioned in a sleeve-note – that “the completing of an instrument must remain in one pair of hands”.

© Semibrevity 2014 – All rights reserved

Also of interest:

The Leonhardt Consort: the early days – with recorder pioneer Kees Otten

REQUEST FOR INFORMATION

Leonhardt’s instruments and the Leonhardt Consort

For future blog posts, I’m trying to discover when Leonhardt owned which instruments (antique or otherwise) and also to re-construct the concert performing history of the Leonhardt Consort.

If you know anything about either, or could suggest other people or possible sources, please get in touch by using the Comments Box below. Your reply will not appear on the blog.

Muziekkring Obrecht c.1959 Recorder pioneer Kees Otten (see this blog post) had his finger in many musical pies. He first played medieval music in 1948, was a jazz musician, taught Frans Brüggen (on which topic there will be a future post) and formed two ground-breaking early music groups.

In 1952, he established the first Dutch group for medieval and Renaissance music: the Muziekkring Obrecht (Obrecht Music Circle). The ensemble performed largely unknown repertoire – ultimately consisting of 600 numbers from the Ars Antiqua to the early baroque – and played very unfamiliar instruments too.

The core group consisted of three married couples: Joannes Collette (fiddle, gamba, lute), Folly Collette (soprano); Hans van den Hombergh (portative organ), Antoinette van den Hombergh (fiddle); Kees Otten (recorder) and Marijke Ferguson (small harp and recorder). A further group of eight singers and instrumentalists could be drafted in, depending on the works to be performed.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

In the beginning, according to Hans van den Hombergh (who mostly conducted the ensemble), there were only quiet combinations of wind instruments, fiddles and harp, and the pieces were often less than a minute long, so that the audience couldn’t nod off. The initial emphasis was on variety of timbre and style.

Van den Hombergh goes on to say that it was only much later that they began to perform larger works and to appreciate the raucous sounds that could be made by cornetti and trombones. They even borrowed the serpent from the Gemeente museum in the Hague!

How it all started

Marijke Ferguson, who had recently married Otten, in 1950, remembers exactly when they decided to set up a specialized ensemble:

In 1951 Kees and I heard a concert in the [Amsterdam] Concertgebouw given by the Brussels-based Pro Musica Antiqua, led by the American, Safford Cape. [Started in 1933, this was the first group in the world dedicated to playing medieval and Renaissance music.]

There and then we decided we should also do something similar, which involved playing different instruments.

The process of finding exactly the right combination of sounds took a lot of time … We had the example of Safford Cape, of course, and knew the records of Noah Greenberg’s New York Pro Musica, but we really just had to work it out for ourselves. Joannes [Collette] was much further advanced in using early instruments than we were. He had a copy of a recorder, made by a German instrument maker. A copy, at a time when such things just didn’t exist!

Kees really had a great affection for the Netherlandish School. He kept coming back to Dufay … Very early on, he was also deeply involved in the music of the [Harmonice Musices] Odhecaton.

At that stage, everything was new to us and he selected all the music and prepared the instrumentation.

Although Otten had formally studied the clarinet at a conservatory (see here), he was a self-taught expert in the field of early music. According to Marijke Ferguson, he was an avid reader, particularly of German musicological publications, and quickly amassed a large library of scores and reference works, which he could use as source material.

Back in the 1950s, before the advent of photo-copiers, and when performing editions of early music were scarce, all the music for the players of Muziekkring Obrecht had to be written out by hand. I recently saw the individual part-books for this group, and they must have taken ages to make.

From 1952 to 1961, Muziekkring Obrecht gave many concerts, mostly in Holland, with occasional trips to Belgium and Germany. They also performed on TV and made several long series of thematic programmes for Dutch radio.

Muziekkring Obrecht produced only one record, an EP for Telefunken’s “Das Alte Werk” made in around 1959, with music by John Dunstable, Dufay, Obrecht and Josquin des Prez. Here’s the full band (soprano, sopranino and descant recorder, fiddle, gamba, portative organ and rattle) in

On the ease with which the ensemble mastered this repertoire, Otten noted:

My familiarity with improvising [in jazz] probably helped me to perform early music successfully. That certain looseness wasn’t something that you often saw, at the time, in other early music groups. Most of them were overtaken by a sort of stiffness when they played … the old composers – that was something that just didn’t happen to me.

The break-up

Partly as a result of the divorce between Otten and Marijke Ferguson, and various other circumstances, the ensemble just fell apart. Otten returned briefly to jazz, Joannes Collette set up the new early music department in the conservatory in Maastricht, and Hans van den Hombergh became a choir and opera conductor. Antoinette van den Hombergh gave up her medieval fiddle and continued to play the baroque violin in the Leonhardt Consort, which she’d been doing since the mid 1950s.

Marijke Ferguson started to teach the small harp and, in common with Folly Collette, was much occupied with her young children. She was later to become a pioneer in her own right, exploring yet earlier repertoire with her own group, Studio Laren, which she established in 1965.

In 1963 Otten began another ensemble, Syntagma Musicum, with his new wife, the recorder player and harpsichordist Barbara Miedema, of which more another time.

Thanks are due to Marijke Ferguson, Marina Klunder (Kees Otten’s widow), and to Jolande van der Klis for her excellent Oude muziek in Nederland which has been a valuable source in writing this post. The English translation of various quotes is my own.

Also of interest

Kees Otten, Dutch recorder pioneer

Frans Brüggen: the early years (1942–1959), with his teacher Kees Otten

The Leonhardt Consort: the early days – with recorder pioneer Kees Otten

Gustav Leonhardt & Martin Skowroneck – Making harpsichord history

Syntagma Musicum, the internationally famous Dutch early music group founded by Kees Otten

© Semibrevity 2014 – All rights reserved

Kees Otten, as a young man

If you’re a fan of Gustav Leonhardt and Frans Brüggen then you might just have heard of the Dutch recorder virtuoso Kees Otten; but he is not much acknowledged, even in Holland. Yet Otten was a musician of great importance for the emancipation of the recorder in Holland, its acceptance as a serious instrument in the concert hall, and the establishment of what we now call historically informed performance practice.

It was largely thanks to Otten’s tenacity (and, in part, the fact that J. S. Bach wrote recorder parts in his works) that the recorder was taken seriously by the Dutch Ministry of Education and given full status as a “proper” musical instrument.

Because of his influence, it began to be taught in schools for the first time, and from the mid 1950s it became possible to take a nationally recognized qualification in the recorder at Dutch conservatories. And this widespread recognition of the recorder, an instrument that is affordable and easy to play to a satisfying standard, helped early music to become established for amateurs in the Netherlands.

A dual musical life

Kees Otten (1924–2008) came from a musical family: his mother was a piano teacher who gave lessons for more than 50 years, but it was his uncle, Willem van Warmelo, who taught him the recorder from 1930 to 1937 – “until I could play it better than he could!”, as Otten remarked – and laid the foundation for what was going to become his ultimate career.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

Van Warmelo, a music educator since the 1920s keen on the German idea of hausmusik (broadly speaking, domestic music-making), was one of the first to bring the recorder to Holland. He was friends with Poulenc and Hindemith, who shared his musical philosophy and, according to Otten, “used all kinds of music in his teaching method, not just old music”.

As it was impossible at that time to study the recorder as a “proper” instrument, Otten took up the clarinet and began classical training at the Amsterdam Muzieklyceum (Music Lyceum) in 1941. But it was jazz, particularly the music of Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton, that caught his imagination and, aged just 15, he had jammed – on the recorder! – with the great American jazz tenor saxophonist, Coleman Hawkins at a club in Amsterdam.

From 1942 he was playing in Bach cantatas conducted by the Bach-expert and harpsichordist Hans Brandts Buys, who was a major influence on Gustav Leonhardt. He was invariably joined by Joannes Collette (1918–1995) who is widely considered the first “real” recorder-player in Holland.

(Collette came from a famously fanatical early music family, where both parents and all five children played different instruments including recorders, a lute, a spinet and, by 1938, they also had a quartet of German-made viols.)

Not surprisingly, it was Brandts Buys, Otten and Collette who were the first people ever in Holland to perform the fourth Brandenburg Concerto with recorders instead of flutes, in a concert in the small hall of the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam.

Although he played baroque repertoire in semi-professional “underground” house-concerts, Otten continued to play jazz and “contemporary music” as a member of various cabaret groups, including the Canadian “liberators” band, the Sing Song Shakers.

His jazz breakthrough could have occurred in 1945, when he was offered a place in a well-known jazz orchestra by Kid Dynamite, for a 30-month tour of North Africa, the Balkans and Spain. But at this time he had a serious girlfriend, Marijke Ferguson (b. 1927; his student and his first wife, from 1950) and had been invited by Brandts Buys to take part in concerts and broadcasts of Bach cantatas. “After some hesitation”, said Otten, “I chose the girl and the Bach cantatas.”

So, in 1946 he was involved in the celebrations for the 25th anniversary of the Dutch Bach Society, performing in the Actus Tragicus (Bach’s Cantata BWV 106) conducted by Anthon van den Horst, and from 1947 onward he participated every year in the Society’s St Matthew Passion.

In the following years, he was to perform internationally with the lutenists Walter Gerwig (from 1952) and Julian Bream (whom he introduced to Holland in 1955), and in ensembles with Carl Dolmetsch (son of Arnold), among others. According to interviews, there were “lots” of concerts with these people, although only a handful are documented in what is probably Otten’s rather incomplete archive.

His recorder teaching career began in 1947 at his old school, the Music Lyceum in Amsterdam and, by May 1954 – including groups at the local music school – he was teaching 130 students every week. He was so successful as a teacher that he was later to work at four Dutch conservatories simultaneously.

The Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble

The Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble in 1954 www.semibrevity.com

By 1948 Otten had established the Amsterdams Blokfluit Ensemble (Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble), then the only professional recorder group in Holland, which consisted of Marijke Ferguson, Frans Douwes and, later, his most famous pupil, Frans Brüggen (second from the left in the photo above). Occasionally they were accompanied by harpsichordist Jaap Spigt.

Interestingly, Jaap Spigt was so uncertain whether he should play with Otten at all – as the recorder at that time had the reputation of being a children’s toy – that he asked his teacher, Janny van Wering, at the time the foremost Dutch harpsichordist, who gave her blessing. Spigt’s relationship with Otten was to prove important for him, as it led to concert tours of the UK, where they played with Carl Dolmetsch, the important English recorder pioneer Edgar Hunt, and others; he was also to accompany Otten in his solo debut recital at the Concertgebouw in 1956, and in almost 90 other concerts. Spigt was later to become a noted choir conductor and was a harpsichord teacher on the staff of the Amsterdam conservatory at the same time as Leonhardt and Ton Koopman.

The repertoire of the Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble ranged from the 15th century through to the 20th and included many pieces specially written for Otten. He cleverly used these new works to promote the reputation of the recorder as a “proper” musical instrument to professional musicians. Also, the Amsterdam Recorder Ensemble’s extensive series of radio broadcasts (which included singers and other instrumentalists, including the young gamba-playing Gustav Leonhardt) and their many school concerts further helped to improve the recorder’s image, as something other than a child’s toy.

Looking at the programmes, you see works by Ibert, Rubbra and modern Dutch composers such as Henning and Zagwijn paired with madrigals, Praetorius, Handel and Purcell, plus a liberal helping of arrangements from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book and Bach’s keyboard music, particularly the Art of Fugue.

Otten was later to become a member of the first incarnation of the Leonhardt Consort, though only for a relatively short period, and to set up Muziekkring Obrecht and Syntagma Musicum, two important groups specialising in the performance of medieval and Renaissance music.

More about Otten in future blog posts.

Thanks are due to Marijke Ferguson, Marina Klunder (Kees Otten’s widow), and to Jolande van der Klis for her excellent book, Oude muziek in Nederland, which has been a valuable source in writing this post. The English translation of various quotes is my own.

Also of interest:

Muziekkring Obrecht – the first ever Dutch ensemble for medieval & Renaissance music

Frans Brüggen: the early years (1942–1959), with his teacher Kees Otten

The Leonhardt Consort: the early days – with recorder pioneer Kees Otten

Gustav Leonhardt & Martin Skowroneck – Making harpsichord history

Syntagma Musicum, the internationally famous Dutch early music group founded by Kees Otten

© Semibrevity 2014 – All rights reserved

Almost two years ago, I attended the funeral of Gustav Leonhardt and wrote a brief blog post which I quickly withdrew, despite the fact that it attracted more attention than anything else which I’ve ever written. Somehow, publishing it just seemed wrong. Almost two years ago, I attended the funeral of Gustav Leonhardt and wrote a brief blog post which I quickly withdrew, despite the fact that it attracted more attention than anything else which I’ve ever written. Somehow, publishing it just seemed wrong.

On the second anniversary of Leonhardt’s passing, I’ve decided that it’s now appropriate to share what I wrote.

Gustav Leonhardt’s funeral was held yesterday in the Westerkerk in Amsterdam, where he and his wife were regular church-goers. The church is just round the corner from Leonhardt’s house on the Herengracht.

Seven hundred people were invited and there were a further 100 places available. Although I’ve not always gone to Leonhardt’s concerts when I could have, I felt sure that I should attend this “farewell gathering” – which was not a service, as no priest was involved.

The church was, obviously, bristling with early music celebrities, from cellist Anner Bijlsma and violinist Lucy van Dael, who both played with Leonhardt from the earliest days, to Bart and Sigiswald Kuijken, who’d joined in later; the recorder player Marion Verbruggen; ex-student Pierre Hantaï; the bass Max van Egmond and Harvard professor, Christoph Wolff, to name but a very few.

Bernard Winsemius who, with Leonhardt, had been joint organist of Amsterdam’s Nieuwe Kerk for more than 30 years, unsurprisingly played only Bach, on the main organ. Before the service, he played the Siciliano from the Harpsichord Concerto, BWV 1053 and the Fugue in b minor, BWV 544b.

In the opening remarks – given in both English and Dutch – we were told that Gustav Leonhardt himself had exactly specified what should happen today, apart from choosing the short Biblical quotations and hymns, with only two or three of the verses of each being sung.

These consisted of Psalm 116 (Geneva Psalter), Hymn 429 (Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten), Hymn 271 (Ach, wie flüchtig, ach wie nichtig) and Hymn 432 (Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan).

We also learned that Leonhardt had written some “profound observations at the end of a long and beautiful life”, which would be read at the end.

When these came, I tried to make notes, but there was just too much to take in, and this distillation of Leonhardt’s philosophy and religious beliefs (given in Dutch with quotes in Latin, French and German) was simply too complicated to grasp fully at first hearing.

The ceremony ended with a reading of the text from the final chorale of Bach’s St. John Passion, Ach Herr, lass dein lieb Engelein, which was then played on the organ.

As we all put on our coats, I smiled and nodded to complete strangers whose eyes, like mine, were welling with emotion and respect for this exceptional musician. He will stay in our memories for a very long time to come.

© www.semibrevity.com 2014. All rights reserved.

Charles Thorton Lofthouse © Hermione Lockyer www.semibrevity.com This short biography of Charles Thornton Lofthouse was sent us by his daughter, Hermione Lockyer, and it is published here with some editorial additions and clarifications. We are very grateful to Ms Lockyer for her generosity in providing this valuable information.

My father, Charles Thornton Lofthouse (1895–1974) had a long and busy career as professor at the Royal College of Music, London (1922–71), director of music at Westminster School and Reading University, founder and conductor of the University of London Music Society, music examiner, and researcher, but he would have most liked to be remembered as a harpsichordist.

He played an important and distinguished part in the re-establishment of the harpsichord as the only instrument for the performance of music originally written for it, and in the development of the art of continuo playing.

The harpsichord had not been his first instrument, however. Early in his career, after the First World War, he had studied the organ with Walter Parratt and conducting with Adrian Boult at the Royal College of Music, and the piano with Alfred Cortot in Paris. As accompanist and continuo player with the London Bach Choir for many years from 1921 onward, he played continuo at the choir’s performances of Bach’s Passions on the piano under Ralph Vaughan Williams’ baton (1921–28) before turning to the harpsichord in performances with Reginald Jacques (conductor 1932–60) and becoming the first person to play a harpsichord in the Royal Albert Hall on 3 April 1938.

A lifetime at the keyboard

My father made a lifetime study of a wide range of keyboard instruments. In the years before he could afford a harpsichord of his own, he was lent a Pleyel belonging to Sir Adrian Boult (conductor of the Bach Choir 1928–31). After the Second World War, he used the cheque presented to him on his resignation as Head of Music at Reading University to acquire a clavichord made by his friend Thomas Goff, a harpsichord and clavichord maker who had also designed a lute for Julian Bream. Tom made him a lovely instrument (now in the possession of Christopher Hogwood) with beautiful hinges and ‘C.T.L.’ inscribed in brass at the end of the keyboard [see a photo here].

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Later my father bought another Goff clavichord with an extra octave in order to play Scarlatti. When Hubert and I, his children, left our Chelsea home my father was able to buy his longed-for harpsichord – a beautiful instrument, also made by Tom.

To Londoners who attended the Bach performances in the Albert Hall and Royal Festival Hall in their thousands, my father was a familiar figure, seated at the modern harpsichord in the centre of the orchestra and playing from a copy of the original full score by Bach of the St Matthew which he had obtained via a friend in Germany.

Charles Thornton Lofthouse performing at Bach Festival, Bath © Hermione Lockyer www.semibrevity.com From its mere figured bass he wove “with a thousand delicate nuances” (as one distinguished critic put it) the extempore harmonies which link orchestra and voices into one organic whole. Another critic commented, “There is a wizardry in the Doctor’s touch”; while Gordon Jacob wrote, “His realisations of thorough-bass were distinctive, yet always idiomatically sound, and added much to the stylishness of the Bach Choir’s performances.”

Over his long career he performed in many places around Britain (Bristol, Bath, Oxford, Reading, Winchester, Liverpool, as well as London and the East Sussex & West Kent Choral Festival) with many well-known musicians, including the pioneering viola da gamba player Ambrose Gauntlett. He played the continuo with Cuthbert Bates conducting in Bath Abbey from the inception in 1946 of the Bath Bach Festival until 1973. At the 1954 Festival he also performed in a concert with four harpsichords, with George Malcolm, Eileen Joyce, and Boris Ord, with Raymond Leppard as harpsichord continuo.

Perhaps the most famous singer he accompanied was Kathleen Ferrier, who made her London debut in 1943, with the Bach Choir at Westminster Abbey. Peter Pears was also a soloist in this performance. She appeared several more times thereafter in the St Matthew up to 1952. Early in the 1950s Decca made a recording of the Bach Choir conducted by Reginald Jacques in a complete performance of the St Matthew. The recording took place in the Kingsway Hall, with Kathleen Ferrier as one of the soloists and my father playing the harpsichord continuo.

He himself conducted the St Matthew Passion, with Ann Dowdall, Helen Watts, Kenneth Woolam, Gordon Clinton and John Shirley-Quirk, in 1962, and on 31 January 1965, he directed the East Sussex & West Kent Festival Choir and Orchestra, at a concert in honour of the 60th birthday of Michael Tippett, in which the Deller Consort, Walter Bergmann (harpsichord) and William McKie (piano) took part.

Gustav Leonhardt

My father was also an inspiring harpsichord teacher who influenced many students at the Royal College of Music during his fifty years there. He taught the harpsichord from 1934 onward; and later in his life, in 1960 [aged 65] he himself returned to study of the harpsichord, taking sabbatical leave to research harpsichord playing with Gustav Leonhardt in Amsterdam and Aimée van der Wiele, a Belgian harpsichordist and former student of Wanda Landowska, in Paris.

Further afield

In 1956, while on an examination tour in New Zealand for the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, my father and Sir Keith Falkner took part in a performance of the St Matthew in Wellington, with my father playing the continuo and Keith singing the part of Christ. [Hear Falkner singing Purcell here, recorded in 1935, with John Ticehurst, harpsichord, and Bernard Richards, cello.]

The New Zealand broadcasting company had ordered a Goff harpsichord from London. Amazingly it arrived at the same time as my father’s visit, and he was the first artist to play it, at a 2YA [radio station] concert broadcast with the National Orchestra from Wellington.

From 1961 to 1965 he toured continental Europe with the Anglian Chamber Soloists. He appeared as a continuo, chamber or solo harpsichordist throughout Europe and in the USA, for instance at the Schloss Mirabell in Salzburg, the Nymphenburg Palace in Munich – on an ornate harpsichord decorated in white and gold to match the baroque ornamentation of the building – and the Eggenberg Palace in Graz.

Bach

My father’s contribution to the study and interpretation of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach stands out with particular prominence in his many-sided career. Not only did he take a leading part in the remarkable revival of Bach’s music during his lifetime, but his special and important achievement was that he revived the harpsichord continuo to its original and intended function in the interpretation of the works of the great master. He gave lecture recitals “In Praise of Bach” and other great composers around the world. He also published Commentaries and Notes on Bach’s Two- and Three-Part Inventions (London, 1956). The cover of this publication was designed by Irene Lofthouse, his artist wife.

In the words of The Times, he was “one of our senior Bachians”, and a doyen of English continuo players.

© Hermione Lockyer 2013

The Father Smith organ at Auckland Castle, 1688 © Richard Hird I didn’t know that the Bishop of Durham’s former residence at Auckland Castle, in Bishop Auckland (yes, really), had been bought by a millionaire – until I started to research visiting there, as a possible day trip, last summer.

The initial draw for the new owner was keeping together a set of thirteen stupendously large biblical oil paintings with a price tag of £15 million. Ultimately, he ended up buying the whole castle and the 800-year-old estate as well; see the full story here.

Prince Charles talks here (on video) about Auckland Castle

Surprisingly, there was nothing on the new glossy website about there being an organ. Once inside the ancient chapel, however, it didn’t take me long to notice that there was what looked like an impressive seventeenth-century pipe organ perched on the back wall, but maybe – as in the chapel of Durham Castle – it was just an old case.

All anyone could only tell me was that the organ was still used for services. At the ticket counter, though, they managed to rustle up a copy of a booklet (reprinted from the Church Quarterly Review, in 1935) by Canon C.K. Pattinson, called The Father Smith Organ in Auckland Castle.

The organ superstar of the seventeenth century

Bernard “Father” Smith was born as Bernhard Schmidt in Germany in around 1630, and was trained there as a master organ builder. At a certain point, he moved to Holland, where he became Barend Smit and, in 1663, built the sensational organ in the Grote Kerk in Edam. See also this article.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

In 1667 he emigrated to England and anglicized his name. The organ historian, Stephen Bicknell, suggested that this career move was in order to profit from the rebuilding of London churches, following the Great Fire in 1666. There was certainly a shortage of organ builders in England during and after the Commonwealth, as a result of the destruction of church organs by the Puritans. Sir John Hawkins noted, in his General History … of Music in 1776:

the makers of those instruments [organs] were necessitated to seek elsewhere than in the church for employment; many went abroad, and others … became joiners and carpenters, and mixed unnoticed with … those trades.

See also this fascinating dissertation: The Pipe Organ in Early Modern England by C.W. Cagle.

After around ten years in royal service Smith was formally appointed King Charles II’s “organ maker in ordinary” in 1681 and as such – according to Pattinson – occupied apartments in Whitehall with a salary of £20 a year.

Battle of the Organs

Smith was the most successful organ builder of his time, and beat his arch-rival, Renatus Harris, in the famous Battle of the Organs held in 1684, which was to decide who should get the contract for the new organ in the Temple Church in London. The fact that Smith employed John Blow and Henry Purcell to demonstrate the capabilities of his organ, which he had specially erected in the church, clearly didn’t hurt his cause.

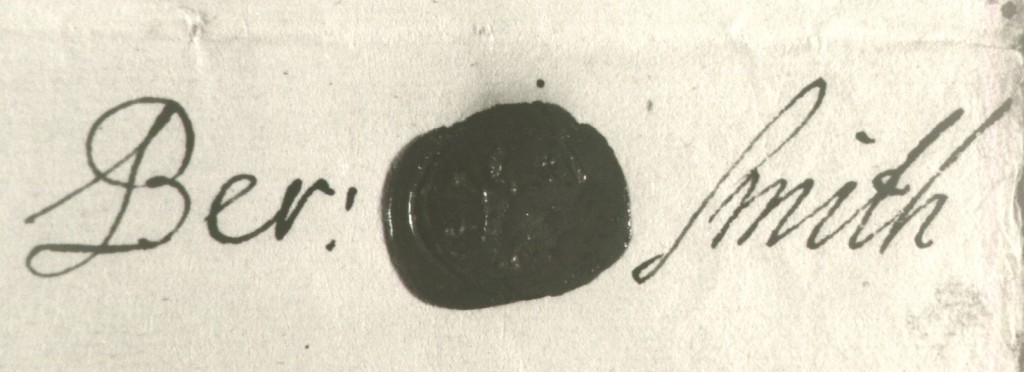

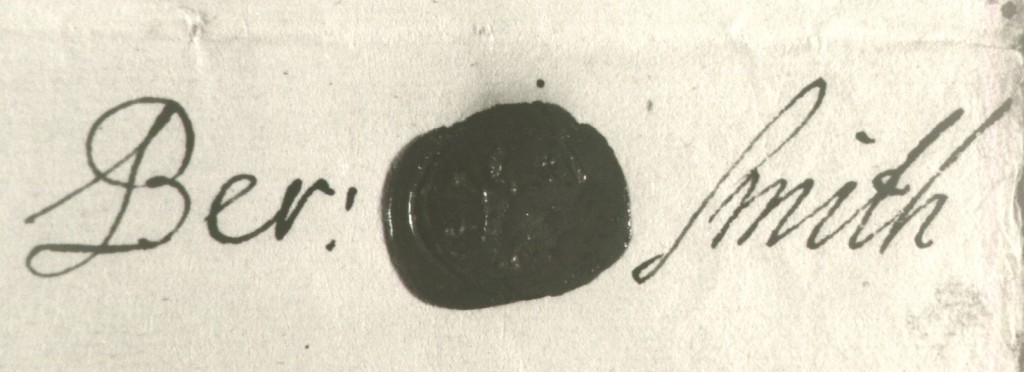

The signature and seal of Bernard Smith Apart from making the organ which was the prize in this contest, Smith also built instruments for Westminster Abbey, St Paul’s Cathedral, Durham Cathedral, the chapel at Windsor Castle and many other churches.

The gift of a Bishop

The organ at Auckland Castle Chapel was specially built for this location in 1688, as a gift from Nathaniel, Lord Crewe, who was the Bishop of Durham from 1674 to 1721.

Although there’s no documentation, which is apparently common with gifts, the Crewe family crest is incorporated into the case decoration, and a slightly cryptic Latin inscription (not shown on the photo above) states that it was given by Nathaniel, Bishop of Durham, and refers to his previous post as Bishop of Oxford.

Is it really a Father Smith?

Pattinson mentions a “tradition” that the organ was by Smith, but there are no documents to support this either and, as Bicknell wryly comments, there are as many organs attributed to Father Smith as beds which were supposedly slept in by Queen Elizabeth I.

However, local organ adviser Richard Hird, who has written an excellent web page on this instrument, giving the current specification and details of the organ’s chequered history, makes a strong case for Smith:

- The Bishop was the secular as well as the religious head of the Palatinate of Durham, a state within the kingdom, which had been largely reinstated after the Commonwealth.

- Much of his time was spent in London – living at Durham House on the Strand – and moving and working in Court and government circles. He was a member of Charles II’s High Commission and was “prepared to go [to] all lengths with the Court”.

- Smith had already built the Durham Cathedral organ just a few years before (for which a contract and letters exist), which the Bishop would have known well.

- Therefore, the organ could not have been built by anyone other than the “royal organ maker”.

In addition, Cecil Clutton observed that Lord Crewe was a man “for whom the best was just good enough”.

The organ case is also very Smith-like, according to early organ expert Dominic Gywnn. And, in an entry in his diary in 1826, the organ builder Alexander Buckingham, who worked on the instrument himself, wrote:

The original maker was Father Smith in 1680 [perhaps a slip of the pen, as 1688 is carved on the case] … names incl. “Mr Smith, organ maker” are wrote on the back of the organ.

These “signatures” have since disappeared.

Even though the organ, in its current state, is a 1903 Harrison & Harrison two-manual and pedal rebuild of a single-keyboard seventeenth-century instrument – which no longer has its original insides (and the internal layout has been rotated 90 degrees and the console is now on the side, not at the back) – it does still have mechanical action, all the pipes from five of the six original stops, the original reverse keyboard and even the ebony stop knobs, as shown below.

The console of the 1903 Harrison & Harrison organ at Auckland Castle, showing the original Father Smith reverse keyboard and five of the six original square-shanked ebony stop knobs (on the right) © Richard Hird Harrison & Harrison’s records give detailed proposals for the renovation and rebuild, and state that the voicing of the old pipework was “to be respected”, and has not been changed.

You can judge for yourself to what extent this is an original-sounding organ, in the pieces played below by Alan Cuckston, using only the Father Smith stops (which are specified next to each title).

Tomkins – Fancy in A (Stopped Diapason)

Handel – Fantasia in C (Stopped Diapason, 15th)

Purcell – Toccata in A (Stopped Diapason, Principal, 15th)

Croft – Voluntary in A minor (Full Organ)

Despite these many changes, this instrument is still very important, as it is one of very few Father Smith organs that is in playing order, albeit in altered form.

Thanks are due to Richard Hird, for answering my many questions and for the photos; to Alan Cuckston, and to Peter Hill of Foxglove Audio, for giving permission to use their recordings of this organ; to Dominic Gywnn; and to Ian Lackenby, of Harrison & Harrison Ltd., for specially inspecting the organ on my behalf.

© Semibrevity 2013

|

Email subscription This feature is no longer available.

|

![Malcolm-George-02[1965]](http://www.semibrevity.com/wp-content/uploads/Malcolm-George-021965.jpg)