Rarely, if ever, have so many letters of condolence and obituaries been written about a Dutch musician as for the recent death of the grand master of the harpsichord and icon of the early music movement. Gustav Leonhardt, the eminent teacher, and a very special person, is no more. On 16 January last, he died at his home in Amsterdam, at the age of 83.

After studying at the Schola Cantorum in Basel (with August Wenzinger and Eduard Müller from 1947 to 1950), he went on to give harpsichord lessons in Vienna until 1955. In Basel, he met his future wife, Marie Amsler, the pioneering baroque violinist, and got to know Alice and Nikolaus Harnoncourt, before they were married.

Leonhardt’s interest in baroque music had already been aroused in the Netherlands by the Bach scholar Hans Brandts Buys and by Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp [who had been his cello and gamba teacher].

His acquaintance with the unique countertenor Alfred Deller was a continuing source of inspiration for him, and their first recording, made in 1954, has been reissued on CD. This was followed by a disc of Bach cantatas, with Leonhardt as organ soloist in BWV 170, and a very poignant rendition by Deller of the Agnus Dei from Bach’s B Minor Mass.

In 1954, Gustav Leonhardt became the harpsichord professor at the Amsterdam Conservatory and remained there until 1988. He had many pupils, and he himself once said to me, at a harpsichord competition in the US, “Everyone in this auditorium calls himself a student of Leonhardt.”

In 1955, he founded the Leonhardt Consort with his wife, Marie, and they sometimes played in meantone tuning. Their recordings of then very unfamiliar music – I vividly remember Muffat, Lawes, Fontana – sounded extremely musical, and Leonhardt’s approach to continuo playing was something that we had never heard before!

The characteristic sound-colour of Skowroneck’s instrument, which he used in Bach’s harpsichord concertos, was also something very new. Leonhardt had seen some excellent copies of old harpsichords in America, and Skowroneck developed this concept in Europe, in a unique way. Subsequently, Leonhardt’s Dulcken harpsichord was copied all over the world.

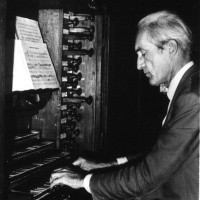

The influence of Gustav Leonhardt as a harpsichordist and harpsichord teacher is justifiably well known everywhere, but as an organist and clavichord player, he has received much less attention. Leonhardt was an organist of long standing, first in the Waalse Kerk and later in the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam. I still remember the only organ lesson that I ever had with him: it was a revelation! I was also greatly impressed by the important Bach recordings that he made on the organ of the Waalse Kerk.

His recordings on the fortepiano were never as influential as they should have been, though his playing was very much ahead of its time. He played on “ce parvenu”, as Voltaire called the newfangled fortepiano, the way a harpsichordist in the eighteenth century would logically have played the piano. Here too, he knew the tradition, and the result was both daring and new.

He gave master classes all over the world, and was a popular and highly entertaining speaker. He was sporadically active as a editor, and his Sweelinck edition is an excellent example of his work. Musicology was very important to him: he needed to understand why the music had been written. He was also unique as a writer of forewords and short articles in the works of other people.

He did not mince his words and he knew his own mind; whether it concerned the colour of seventeenth or eighteenth century window frames, or his distaste for everything from the nineteenth century. He loved everything that was old which, for him, represented refined taste, and he was an avid collector of many different things [including furniture, silver, porcelain and musical instruments]. It was always extraordinary to talk to him about art.

In my time with him, as a student, often spent in his fine Bartolotti house, the car was simply a means of transporting harpsichords. Later, however, he became interested in fast cars. He always drove at high speed and thoroughly enjoyed it.

Gustav Leonhardt preferred lightly quilled harpsichords. Apart from Bach, Frescobaldi and Froberger, French music and French harpsichords were amongst his greatest loves. And he promoted them with all his heart and soul and intellect. He regarded composers, especially the genius Bach, not as his equal, but was honoured to be allowed to perform their works. His performance in the role of Bach, in Jean-Marie Straub’s Chronik der Anna Magdalena Bach, which was filmed during my studies with him, is memorable indeed.

The recordings he made with Nikolaus Harnoncourt, of all Bach’s ecclesiastical cantatas, with choirboys as soloists and somewhat unpredictable historical instruments, was – in many ways – his life’s work. In 1980, he received the Erasmus Prize, together with Harnoncourt, for this project. Their performances form the benchmark against which all subsequent recordings may be judged.

The illness which came shortly before his eightieth birthday, which resulted in him having to cancel many concerts and almost killed him, unfortunately recently came back. Gustav Leonhardt once said, “I have had a long and beautiful life.” Around a month after his last concert in Paris, he died.

This last performance was regrettably recorded on a mobile phone and posted on YouTube, although everyone knew that he would not have wanted this. This would have hurt him.

We miss him.

Here’s a link to Dutch radio’s Leonhardt tribute page.

Apart from a video of a very star-studded Bach cantata, there are sound files from some very old radio programmes, including a recording of a Bach Partita made in 1959. Right at the bottom of the page, there’s a recital recorded in 1965 which was given on the then newly-restored Müller organ of the Waalse Kerk in Amsterdam, where Ton Koopman had that single lesson.

In the notes, there is mention of Leonhardt typically playing music by unknown composers which he had recovered from “under the dust”!

Thanks are to due to Ton Koopman and Jolande van der Klis (editor of the Tijdschrift Oude Muziek) for permission to translate and reproduce this tribute, which originally appeared in the February 2012 issue.

Translation © www.semibrevity.com

See also this post:

Gustav Leonhardt (1928–2012), the end of an era

[…] “A Long and Beautiful Life”: A tribute to Gustav Leonhardt by Ton Koopman […]

I attended a concert Mr. Leonhardt gave at Harvard University in 1976, to dedicate the rebuilt organ at Memorial Church on Harvard Yard, the main campus. He played some organ music and then some pieces on the harpsichord.

Two things stand out from that night. During the harpsichord performance, he threw in a short riff of a few notes from Dvorak’s New World Symphony and cast a discrete sideways glance at the audience to see if any had caught his little joke. Of course, being the well educated music city that Cambridge is, a number of us did catch the little joke and smiled.

Later, at a reception for Mr. Leonhardt, my two friends and I had a chance to talk to him, and he was very friendly, kind and courteous. Afterwards, we three walked across Harvard Yard and discussed how insignificant and dumb we felt in his presence. In my almost 65 years (as of June 2015) I can say that although I have met a number of prominent artists, musicians and intellects, that Gustav Leonhardt was the only true genius that I have ever met. I treasure the memory of that night.