|

|

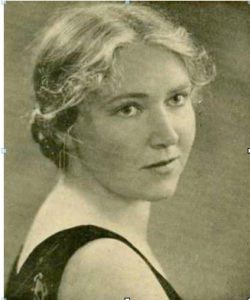

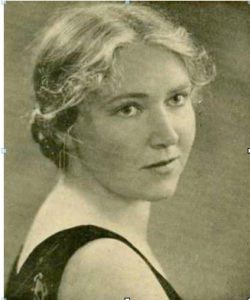

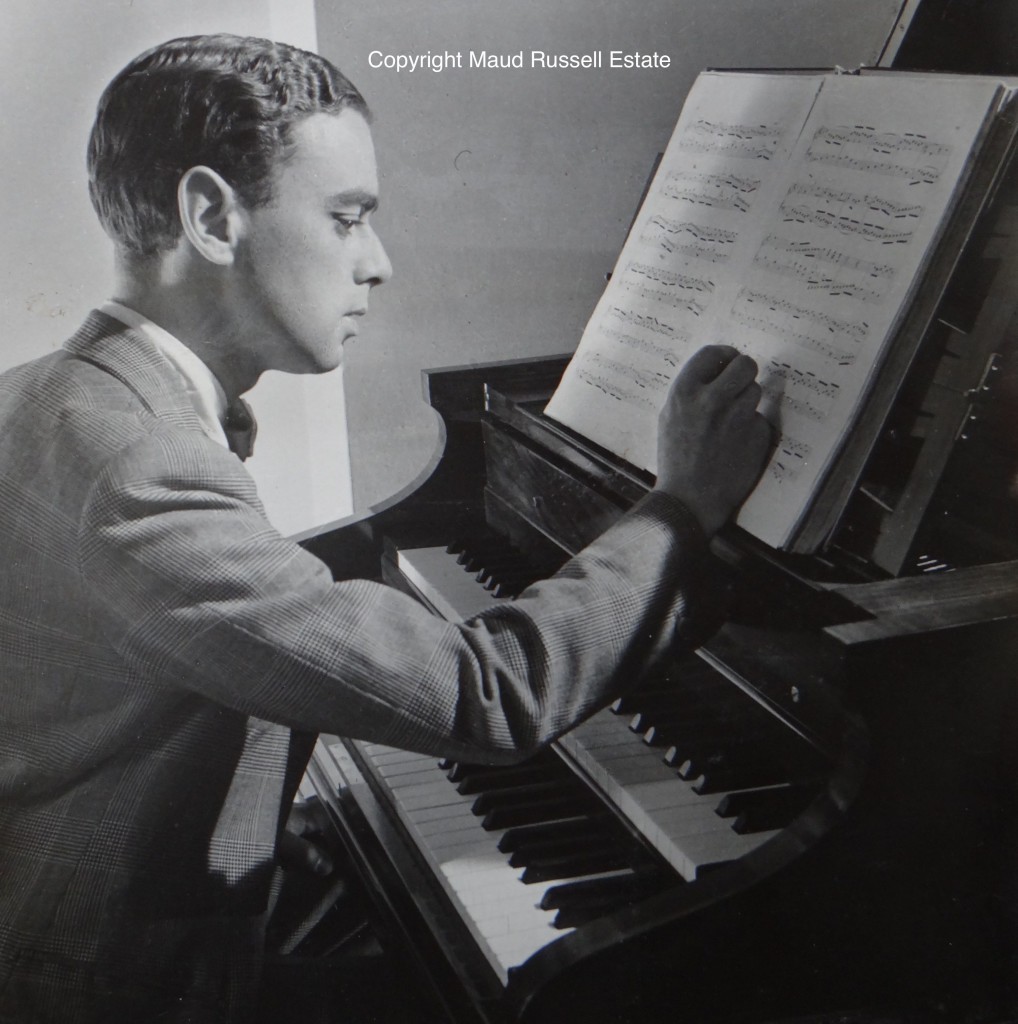

Janny van Wering in 1934 © H. Wirth 2018 Janny van Wering (1909–2005) was the first professional Dutch harpsichordist of the twentieth century. Inspired by leading pioneers of early music such as Wanda Landowska, Pauline Aubert and Arnold Dolmetsch, van Wering’s performances, as well as her teaching, played a large role in reviving the popularity of the harpsichord in the Netherlands.

Van Wering was born in Oude Pekela, where her father was a doctor and also mayor of the village. Following his untimely death in 1918, her mother took the family to Groningen, where Janny continued her piano lessons, which she had started at the age of eight. As she showed exceptional talent for the piano, she was offered a place at the conservatories of both The Hague and Amsterdam when she was only seventeen. She decided upon Amsterdam (so that she could study with Martha Autengruber and, later, with Paul Frenkel), and together with her mother and brother she moved there before she finished high school.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail.

If you would like to help us to get more readers, then please “like” this page, at the top, and “like” Semibrevity, on the right. And do share this post with your friends!

Following her final piano exam in 1932, the Director of the Conservatory, Sem Dresden, advised her to study the harpsichord (as he knew she was keen on Bach). He told her: “In Holland, there will be room for only one harpsichordist.” Two years of harpsichord study followed with Richard Boer in Amsterdam and with Pauline Aubert, largely in Paris. Aubert, the famous French harpsichordist, who had been a student of Arnold Dolmetsch, had frequently given lectures on historic performance practice for the piano teachers at the Amsterdam Conservatory, and it was here that they had first met and started lessons.

After passing her harpsichord exams in 1934, van Wering was awarded the prestigious Julius Röntgen prize (which allowed her to study further in Paris), and so began her career as the first ever qualified Dutch harpsichordist.

She made her debut in the Recital Hall of the Concertgebouw on 9 February 1935, playing works by Sweelinck, Frescobaldi, Bach, Couperin and Scarlatti. The concert was well received by both the audience and the critics, one of whom described her as “ a trail-blazer … with a high level of musicality, intelligence and taste”.

A self-taught continuo player

Van Wering taught herself how to play basso continuo from a figured bass (primarily using F.T. Arnold’s 1931 book on the subject), and this led to her becoming the most sought-after continuo player in Holland for large choral works. Much later, she was to play for performances of the St Matthew Passion by the Concertgebouw Orchestra, given under Eduard van Beinum and Eugen Jochum.

During the war, she played at the Rijksmuseum, often repeating the same programme every day for week, organised house concerts for up to 100 people, taught piano privately and, for three years, took a class of fifty unruly children at a music school. She also began work as harpsichord teacher at the Amsterdam Conservatory in 1944.

After the war, Janny van Wering was employed by the Dutch Radio Union, to give two concerts a week, which she did for the next 24 years!

Around the same time, the Radio Chamber Orchestra was formed; Janny van Wering was a founding member who remained until 1969. As there wasn’t much harpsichording to do, because of their rather limited baroque repertoire, she would often accompany singers on the piano and would even sometimes end up playing the celeste.

She played in many ad-hoc ensembles throughout her career, and performed regularly in the Concertgebouw with the likes of Alfred Deller, the violinists Theo Olof, Szymon Goldberg and Jaap Schröder (who was concert-master of the Radio Chamber Orchestra from 1950), the flautist Frans Vester, the oboist Han de Vries, the cellist Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp and the alto Annie Hermes.

Van Wering also appeared in many different ensembles on disc, and performed with all the important pre-Leonhardt generation of musicians who laid the foundations for the early music “mob” (Janny’s word) that was to follow. Curiously, she made very few solo records.

Janny van Wering in 17th-century costume, 1948 © H. Wirth 2018 From 1947, she taught harpsichord and ensemble playing, with Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp, at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague.

She was famous for her interpretation of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, which was a considerable concert rarity at that time. A review in the Algemeen Handelsblad in 1950 began: “The Dutch harpsichordist Janny van Wering delivered an artistic performance last night in the Concertgebouw, which should be world-renowned.”

She was also interested in musicology and produced two editions, as well as penning many unpublished writings on subjects ranging from ornamentation to basso continuo. Apart from the baroque repertoire, she regularly performed contemporary music; she had a special affinity for the works of Frank Martin and performed his harpsichord concerto and Petite symphonie concertante several times. Many composers wrote both solo pieces and chamber music for her.

Janny van Wering once commented that the 1950s were the climax of her career, as she never gave as many solo performances in later years as she had in that decade.

Collaboration with Frans Brüggen

Although she had dispelled the doubts of her student, Jaap Spigt, about playing with recorder virtuoso Kees Otten, Janny van Wering admitted that she had not taken the recorder very seriously herself before playing with Brüggen, in 1954, during his debut radio broadcast. For her, the recorder summoned up the spirit of the Socialist Workers’ Youth Movement (the AJC), which promoted physical exercise, folk dancing and amateur music-making – mostly on recorders – as a means of developing and educating young people.

However, she described the recording session in 1954 as “a revelation”, so much so that, after the broadcast, she offered to play with Brüggen again, and they subsequently performed a great deal together.

In the late 1950s they gave a series of 15 or 20 school concerts with the violinist Jaap Schröder (with whom they made a record of Telemann Trio Sonatas in 1958).

Although Brüggen often played with Gustav Leonhardt, his collaboration with van Wering continued until at least 1963, when they gave a concert together in the Amsterdam Concertgebouw in May and a radio broadcast for the BBC’s Third Programme in September.

(See Semibrevity, Frans Brüggen: the early years (1942–1959), with his teacher Kees Otten, here)

Listen to G.P. Telemann – Sonata in C played by Frans Brüggen and Janny van Wering.

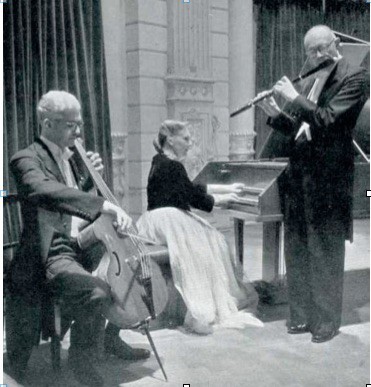

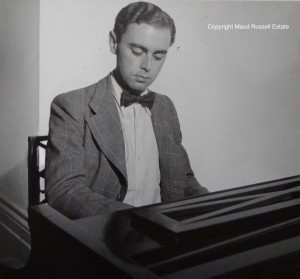

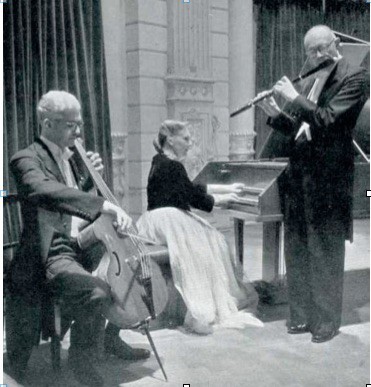

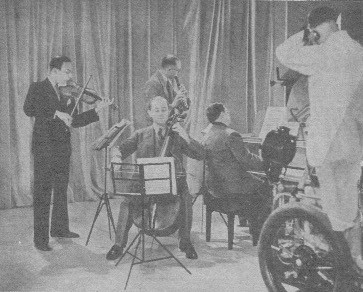

When the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra was founded in 1954, Janny van Wering became their harpsichordist. With this orchestra, she made concert tours to Japan, America and Australia. Also her work with ensembles took her abroad; Sonata da Camera, with Willem Noske, Piet Nijland and Victor Bouguenon, which she joined in 1967, not only toured all over Europe but went as far as South America. Including solo programmes and studio concerts with the Dutch Harpsichord Trio (Janny, Johan Feltkamp, flute, and Piet Lentz, gamba), see photo below, she made around 20 broadcasts for the BBC, starting in 1946.

Meeting with Gustav Leonhardt

In 1955 Gustav Leonhardt returned to the Netherlands from Vienna; he had previously studied organ and harpsichord in Basel and was thoroughly acquainted with historical performance practice. Janny van Wering observed:

Janny van Wering and Gustav Leonhardt c. 1955 “He turned out to be a very nice man. In the beginning, we played together, and with one or two other harpsichordists [in concertos, in concerts and on records]. I knew very quickly that he was my superior, in all respects really: in terms of common sense and musicality.

He also understood the importance of using historical harpsichords or instruments that were copied from historical examples. Leonhardt had a very good brain, he had studied very well and knew from comparing original instruments in museums which harpsichords were worthwhile. He also had the money to buy old instruments, and understood that [if he was to own any] he would have to get in quick. He came from a business background, I was from a doctor’s family.”

Van Wering accepted another teaching post in 1957, this time at the Rotterdam Conservatory, where she taught harpsichord and ensemble playing for the next 17 years.

Instruments

Janny van Wering with Johan Feltkamp, flute; Piet Lentz, gamba, and the Neupert c.1947 © H. Wirth 2018 Perhaps because she had been brought up on an all-wooden Gaveau at the Amsterdam Conservatory, van Wering chose, in 1933, to buy a six-pedal Neupert harpsichord (at a cost of 2000 guilders) which didn’t have an iron frame. Later, she also owned a gargantuan Pleyel. She normally took the Neupert on tour until, in 1963, she bought a two-manual historically inspired Rainer Schütze instrument (884, lute), without pedals.

Listen to Janny van Wering playing Bach on the Schütze

Although Janny van Wering officially retired when she was 65, in 1974, she continued with the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra for another year; it was with them that she made her final recording, of Haydn’s Concerto for harpsichord in D major.

In her regular work, she was succeeded by five harpsichordists: Bob van Asperen at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague; the American, Glen Wilson, with the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra; elsewhere, three of her students took over: the Belgian, Maria Kogan, at the Rotterdam Conservatory; Jaap Spigt joined the ensemble Sonata da Camera; and Marijke Smit Sibinga assumed van Wering’s radio commitments.

In the year of her retirement, she was made Knight in the Order of Orange Nassau, and in 1975 was awarded the Silver Medal of Honor of the City of Amsterdam.

Janny van Wering died in Amsterdam on 1 March 2005, aged 95.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the Dutch pianist, harpsichordist and musicologist, Henriëtte Wirth, on whose PhD dissertation this post is primarily based. The whole dissertation (in Dutch), about Henriëtte’s great aunt, Janny van Wering, is available to download here.

As ever, that excellent book, Oude muziek in Nederland, by Jolande van der Klis, has been a valuable source; the English translation of various quotes is my own.

© Semibrevity 2018 – All rights reserved

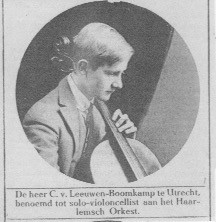

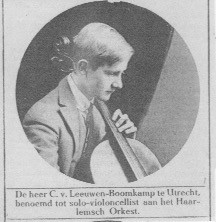

Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp c.1960, by kind permission of P.A.X. Reintjens (from “Luister”, April 2000) © 2017 Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp (1906–2000) was one of the early Dutch pioneers of historically informed performance. He prepared editions from composers’ manuscripts and original printed sources and reintroduced the viola da gamba and violoncello piccolo into the musical life of Holland in the 1920s and 1930s.

What’s in a name?

As Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp himself appreciated that his name was a bit of a mouthful, he often shortened it to Carel Boomkamp, particularly when he was abroad. Jaap Schröder, who knew him well, told me that he would often say, “Let’s leave the lions at home today” (leeuwen is “lions” in Dutch).

The fifth of six children, he was born in Borculo, in the east of the Netherlands, where his father was a clergyman. He began playing the cello when he was eleven, and left school at the tender age of fifteen, to study in Paris with Gérard Hekking, who had been principal cellist of the Concertgebouw Orchestra from 1903 to 1914 (and was later to teach Tortelier and Gendron).

Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp in 1925 © 2017 Boomkamp returned to Holland in 1925 to become the solo cellist of the Haarlem Orchestral Society. Shortly after he turned twenty, he landed the same job with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, making him the youngest solo cellist in the history of that orchestra.

Speaking at a rehearsal, Willem Mengelberg, the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s conductor, told Richard Strauss, “He’s just out of the egg, but he plays the cello magnificently”. Not enjoying Mengelberg’s “heavy German pathos”, Boomkamp left in 1930 to work as a soloist, play a great deal of chamber music and teach at the conservatories of Amsterdam, Utrecht and The Hague where, from the late 1940s, he took the ensemble class with the harpsichordist Janny van Wering.

Boomkamp became interested in early music while still a teenage student in Paris, through studying the cello suites of Bach. He was surprised by all the very different editions that were available, and then came across a facsimile of Bach’s autograph, which was a revelation to him, and that was the beginning of his interest in “authentic” performance. At this time, he also “discovered” the works of Antoine Forqueray and Marin Marais and had copies made of the originals.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

The viola da gamba

Boomkamp taught himself to play the gamba in 1926 using the Tratado (1553) of Diego Ortiz and an antique viola da gamba borrowed from the private musical instrument museum of the wealthy banker Daniël Scheurleer, who lived in The Hague. Take the virtual museum tour here.

As this instrument “had a very light timbre and six strings”, he decided to have a heavier seven-string gamba, with a very large sound, built by the Amsterdam violin-maker, Max Möller Snr. Boomkamp explained:

At that time, in the St Matthew Passion, singers performed as if they were on the stage in La Traviata, so you couldn’t possibly balance that with a subtle [small] gamba sound. Also, everyone was used to the sound of the cello, so the way in which I played the gamba obbligati was a compromise. Back then, a large sound was everything, and the gamba sound that we now have would have just been considered to be a thin squeak.

Boomkamp first played the viola da gamba in the St Matthew Passion in 1929 in the first complete performance given in Holland, by the Dutch Bach Society in the Grote Kerk in Naarden. He continued with the Bach Society until well into the 1960s, and also played for performances with the Concertgebouw Orchestra after the war.

Teacher and researcher

Boomkamp taught for over 40 years, and his students included – as well as half of the cello section of the Concertgebouw Orchestra – Gustav Leonhardt and the cello superstar, Anner Bylsma.

Anner Bylsma remembers:

At the conservatory, [Boomkamp] introduced me to old bows and the old way of bowing, which, at that time, I didn’t do much with. However, later, when I came to play with Frans Brüggen [and Gustav Leonhardt] in 1960, these wise lessons were of enormous use to me.

Leonhardt learned the cello and gamba with Boomkamp from the age of ten, and was taught Marin Marais’s table of ornaments (sowing the seeds for what was to come later). He particularly liked playing the gamba with an old bow. When Leonhardt returned from Vienna, he accompanied his former teacher in several concerts.

Boomkamp was one of the first to understand the importance of bows in creating an “authentic” sound, and wrote about this in De klanksfeer der oude muziek … (The Sound Atmosphere of Early Music …) in 1947.

His research was based on the examination of manuscripts and early editions and his practical experience with early bows and the old musical instruments that he had started buying in the 1920s. A catalogue of his important and extensive collection (now, sadly, housed in a storage depot at the Gemeente Museum in The Hague) was published in 1971.

Repertoire and ensembles

Like many other pioneers, Boomkamp played standard repertoire along with early music, sometimes combining very different periods, and the gamba and cello, in the same concert. One extreme example was in December 1939, at the Concertgebouw, when he played Telemann’s Suite in D major for viola da gamba and strings (watch and listen) followed by the Cello Concerto No.1 by Saint-Saëns. (watch and listen)

In Holland, he was the first to play Haydn’s Cello Concerto in D authentically, with oboes and horns and a five-stringed violoncello piccolo. He also had a keen interest in contemporary music, introduced many new works and had several pieces specially written for him by Henk Badings, Johannes Röntgen, Anthon van der Horst, Rudolf Escher and Hendrik Andriessen.

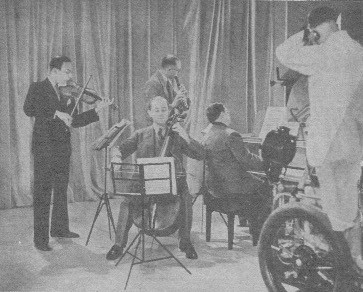

He was the gamba player and cellist of Musica Antiqua probably the first professional Dutch early music ensemble (active from 1935 to 1948),

Musica Antiqua, at the BBC, in 1937 © 2017 with the flautist Johan Feltkamp and the violinist Nicolas Roth (both from the Concertgebouw Orchestra), and with Erwin Bodky on the harpsichord. Their first BBC radio broadcast was in June 1937, when they were described as “seasoned Radio Hilversum performers”, and they made around 15 programmes, excluding the war years. They also performed at least once for the BBC’s new-fangled television, as the photo (used in a Concertgebouw programme) shows.

In 1938, Boomkamp formed a very famous, and short-lived, trio with Russian pianist Alexander Borovsky and Nicholas Roth, and he gave many concerts with the pianist Eduard van Beinum (who was also Mengelberg’s assistant).

He was a member of Alma Musica (1947–1964), an ensemble consisting of violin, viola, cello/gamba, flute, oboe d’amore/cor anglais and harpsichord which played and recorded both early music in many different combinations, as well as contemporary works specially written for them.

In 1952 he established the renowned Netherlands String Quartet, with Nap de Klein, Paul Godwin and a very youthful Jaap Schröder. He formed the ensemble Sonata da Camera, with the violinists Willem Noske and Piet Nijland and harpsichordist Hans Schouwman, in 1958.

Significance

Boomkamp was a top-flight soloist who had toured extensively in a dozen countries by 1938, when he was listed in the Dutch National Biography; he was one of the founding fathers of the Dutch early music movement, and features prominently in Van der Klis (see below). He was an erudite collector of instruments and the teacher of generations of cellists and gamba players, all of whom he imbued with the spirit of historical performance practice. Although in later years he performed mostly in ensembles, he was particularly famous for his interpretation of the Bach cello suites, and was the first to play the sixth suite on a violoncello piccolo (using a re-imagined instrument made by Möller, who didn’t believe that such a thing had ever existed).

In Holland, he was a much-loved and respected institution and when he died, in 2000, significant obituaries appeared in all the major newspapers and musical magazines.

Acknowledgments

Once again, that excellent book, Oude muziek in Nederland, by Jolande van der Klis, has been a valuable source in writing this post; the English translation of various quotes is my own. Thanks are also due to Jaap Schröder.

© Semibrevity 2018 – All rights reserved

The Galliard (La Romanesca), from Court Dances and Others, Revived by Nellie Chaplin, 1911 By Guest Blogger: Mandy Macdonald

Scholarship and spectacle

There is a fragrant air about the concerts of old music that the Misses Chaplin give… But the romantic appeal of the old instruments and the old manner of presenting music does not banish scholarly accuracy on the one hand nor more specifically musical pleasure on the other.

This Times reviewer, writing in October 1927, exposes a tension between scholarship and entertainment in the Chaplins’ presentation of early music. First, the programmes needed popular appeal and had to be performable rather than historically accurate in every detail; second, musicology was a relatively young field, and much academic knowledge that musicians take for granted today simply wasn’t accessible. Although so many of Nellie’s events sailed under the flag of “ancient dances and music”, they occasionally included new or contemporary works based on old tunes or poems alongside works by Byrd, Morley or Purcell. Several examples appear in the records of the Oriana Madrigal Society, founded in 1904 to promote the performance of Elizabethan music. As well as the April 1916 concert mentioned here, on 19 December of that year, the Chaplin String Quartet plus a singer and oboist gave the first performance of Holst’s Four Old English Carols; while on 10–12 April 1919, a three-part concert illustrating “music and dance in Shakespeare’s time” included the first performances of Balfour Gardiner’s settings of two early English songs.

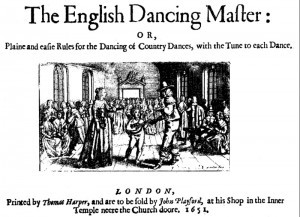

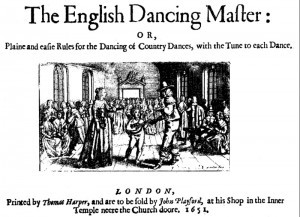

It is unlikely, then, that Nellie was seeking to establish “authentic” scores for the dances, though she owned a copy of Playford’s Dancing Master in an edition of 1665 and another of the 17th edition of 1716. She relates that one of her collaborators went to the British Museum to verify the original orchestration of a sarabande by André Destouches (1672–1749), which they were scoring from a solo piano version. But countless examples of pavans, galliards, allemandes, courantes and so on by familiar Renaissance and Baroque composers were in print at the time and, as the concert programmes and reviews show, provided the music for the court dances. The English pieces from Playford were “harmonized” for the Chaplins’ usual musical forces – strings old and new, oboe, and harpsichord – by a number of collaborators: It is unlikely, then, that Nellie was seeking to establish “authentic” scores for the dances, though she owned a copy of Playford’s Dancing Master in an edition of 1665 and another of the 17th edition of 1716. She relates that one of her collaborators went to the British Museum to verify the original orchestration of a sarabande by André Destouches (1672–1749), which they were scoring from a solo piano version. But countless examples of pavans, galliards, allemandes, courantes and so on by familiar Renaissance and Baroque composers were in print at the time and, as the concert programmes and reviews show, provided the music for the court dances. The English pieces from Playford were “harmonized” for the Chaplins’ usual musical forces – strings old and new, oboe, and harpsichord – by a number of collaborators:

“All the tunes are written for the treble violin alone. They are full of vitality, and further charm has been given them by the simple harmony which has been added for String Quartet and Oboe by Mr. R.L. Cox [and three others].”

Although the dances were mostly arranged by others, Nellie published three books on English dances. In 1909 the Curwen Press published her Ancient Dances and Music, a selection of six Playford dances, which went into further editions. In 1911 it published her Court Dances and Others: An invaluable guide to the manners and protocols of the dance floor with step guides and musical score for amongst others the Pavane, the Irish Jig and the Chacone, also from Playford. And 1913 saw the publication of a small book containing a minuet arranged by Carlo Coppi to music by Philip Hayes, and a gavotte arranged by Lucia Cormani (the teacher of her niece, Dorothy) to music by Thomas Arne, both dances “as arranged for Nellie Chaplin’s revival of Ancient Dances and Music at the Royal Albert Hall Theatre in 1904”.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

The Chaplins’ approach to early music could not be described as purist, rather as populist and “period”. Nellie was not a scholar like Edmund Fellowes or the editors of the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book; but she was exploring something new, inspired by a sincere desire to widen the range of pre-Classical music and dance available to the early twentieth-century public.

Where Nellie was seeking authenticity was in the dance steps and figures, which she studiously copied and “traced” from the originals in museums. Her research into dance was extensive, and broke new ground, as she herself recognized:

I think I am justified in claiming the right of priority in reviving the Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, Chaconne. Canaries, Rigaudon, Passepied, Tambourin, Bourrée, Forlana, and the Galliard and Tourdion.

This work became important to the English folk dance and song revival movement spearheaded by Mary Neal, Clive Carey, and Cecil Sharp.

Spreading the message

Teaching was a large part of the professional lives of Nellie and her sisters. All three are described as teachers in the national census of 1911 and their teaching activities are mentioned from time to time in the records we have of them. Nellie opened her own Pianoforte Foundation School as early as 1893 and by 1907 ran a school of early and country dancing in London, as the newspaper advertisement on the right shows. All three are described as teachers in the national census of 1911 and their teaching activities are mentioned from time to time in the records we have of them. Nellie opened her own Pianoforte Foundation School as early as 1893 and by 1907 ran a school of early and country dancing in London, as the newspaper advertisement on the right shows.

Young people were involved in the early dances both as performers and audience. Nellie was concerned that students were being taught to play Baroque music without ever seeing what the movements of the familiar suites were like when actually danced:

There is a special educational purpose in the revival of the dances of the suites, for young people are constantly taught to play Couperin, Bach, and Handel [without] a clear notion of what the actual rhythm of the dance measures is, and they cannot get the notion so readily by any other means as by seeing them danced, except indeed by dancing themselves. (The Times 27 November 1911)

She was also always ready with information about the harpsichord: in her 1922 article she writes that audience members very often came up to her after performances of The Beggar’s Opera to ask about the instrument, its mechanism, history, and playing technique. In 1911 she gave daily demonstrations of the harpsichord at a weeklong exhibition of modern and early keyboards, and over her long career provided the musical illustrations for many lecture-recitals on subjects such as the evolution of the piano and the Couperin family.

Coda: Nellie Chaplin, national treasure

Nellie clearly became a national treasure: according to a 1924 review, “the dances were in the hands of Miss Nellie Chaplin – praise is therefore superfluous.” When she died in April 1930, tributes poured in. Kate, replying to Percy Scholes, author of The Oxford Companion to Music, wrote touchingly that over 400 letters of condolence had arrived. “We have indeed lost a very dear and loving sister”, she wrote; “we were, as you know, such a devoted trio, and her passing has left a great big gap. She was so much loved, and her work was always so sincere.”

Among her obituaries, this one from the Morning Post of 19 April 1930 is typical: “Her unwearied and unselfish enthusiasm for the music of the past had an incalculable influence on the revival and preservation of its popularity.”

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Jeremy Barlow, who first mentioned the Chaplin sisters to Semibrevity; Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation; Professor Freia Hoffmann of the Sophie Drinker Institut in Bremen, who kindly shared her very extensive research; Sandy Mitchell; and Michael Mullen and Elizabeth Wells of the Royal College of Music.

© Mandy Macdonald 2017 – All rights reserved

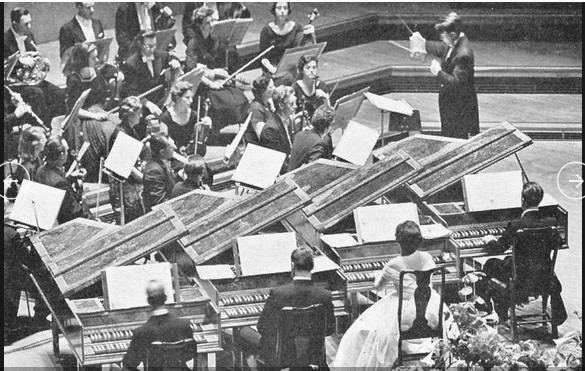

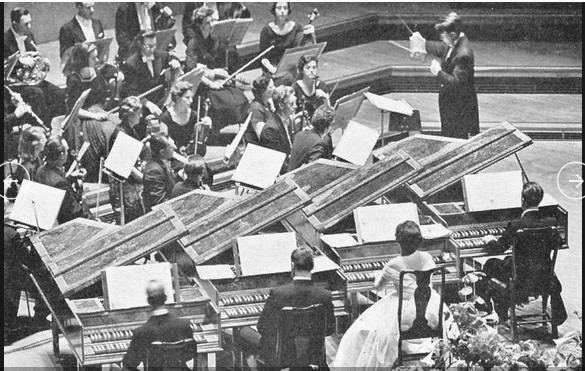

Four Goff harpsichords at the 1961 “jamboree” at the Royal Festival Hall James Gardner has made a fascinating oral history programme for Radio New Zealand about Thomas Goff (1898 – 1975), the British lawyer-turned-harpsichord-maker who was related to royalty. Although he made very few instruments, they were highly prized in the 1950s and 60s by the likes of George Malcolm and Thurston Dart, much in demand for concerts, broadcasts, and recordings and were featured in the very popular multi-harpsichord “jamborees” at the Royal Festival Hall.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

Listen to George Malcolm’s Variations on a Theme of Mozart, for four harpsichords, specially written for these annual RFH concerts, to showcase the broad palette of colours and effects available on the Goff instruments.

According to Jessica Douglas-Home, in her book “Violet”, on the pioneer harpsichordist Violet Gordon Woodhouse, Tom Goff was not just a harpsichord maker:

In spite of all Dolmetsch’s pioneering work, it was still unusual for authentic instruments to be used in concert halls for programmes of seventeenth- or eighteenth-century music. Tom [Goff] was determined to ensure that they should be regarded as an essential part of the proceedings rather than a quaint archaic option. […]

In the cause of his crusade he shamelessly exploited both his musical and his society contacts; and by the 1960s few dared perform eighteenth-century works with solo or continuo keyboard parts other than on a harpsichord.

Until now, very little was known about Thomas Goff’s life, working methods and inspiration, which makes this new research very welcome indeed!

The original Radio New Zealand blurb is reproduced below, by their kind permission:

The Fall and Rise of Harpsichord 6

In August 1956, a beautiful new harpsichord arrived in Wellington aboard the RMS Rangitoto. It had been very recently made by Thomas Goff (1898-1975) of London and before being shipped, it was played by George Malcolm at a concert in the Royal Festival Hall. Goff’s instruments were considered at the time to be “the Steinways of harpsichords”.

Now, it had been purchased by the New Zealand Broadcasting Service for use by the National Orchestra in baroque repertoire and everybody had high hopes for it. It was introduced to the public within a couple of months at a concert in the Wellington Town Hall of Bach’s ‘St Matthew Passion’ [played by Dr Charles Thornton Lofthouse].

The concert was a notorious disaster – no fault of the harpsichord. However, within a few years the instrument fell out of favour and into decline. It sat for decades in the studios of Radio New Zealand, unused and unloved. What went wrong?

James Gardner delves into the colourful and quirky story of Thomas Goff’s Harpsichord No. 6 and of Goff himself. He talks to Peter Averi, retired musician and broadcaster, who was the first person to play the instrument when it was unpacked in Wellington, and to two British harpsichord makers, John Rawson and Peter Owen, who worked with Goff in the 50s and 70s respectively. We also hear the voice of Thomas Goff [in a rare reconstructed radio interview].

But was there a happy ending? The instrument is now owned by Donald Nicolson [who studied with Ton Koopman] and he refers to it affectionately as The Beast. Gardner talks to Nicolson and to instrument technician Paul Downie about the trials and tribulations of trying to get it back into some sort of better-than-reasonable playing condition.

Listen to the complete hour-long programme

Copyright © 2017 Radio New Zealand & Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

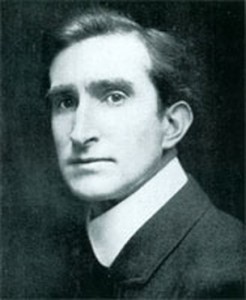

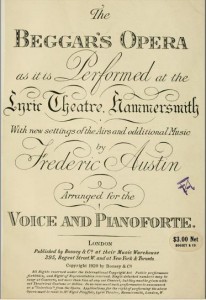

Model of the set design for The Beggar’s Opera, 1920 In May 1920, the opera singer Frederic Austin (1872 – 1952) went to see Nigel Playfair and, over tea and biscuits, they devised the idea of staging a revival of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera, which had not been produced in London since 1886.

Playfair knew some of the songs from childhood, and Austin was familiar with much eighteenth-century repertoire, as he had also been a professor of harmony and counterpoint at Liverpool. There and then, he played through an old score that Playfair had, “arranged by good Pepusch with figured basses and all” and, according to Playfair, he “jumped at the idea” of making an updated version.

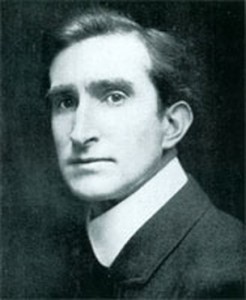

Frederic Austin Austin had just formally retired from the operatic stage, having sung the role of Count Almaviva in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro, for Sir Thomas Beecham at Covent Garden. Due to financial problems, the Beecham Opera Company had closed its doors and so he, and the rest of the singers, were unemployed. The three men knew each other well, as Playfair had produced several operas for Beecham, including this last Figaro; he had also produced plays at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Playfair was a lawyer-turned-actor-manager who, with his business partner, the playwright, Arnold Bennett, had taken over the lease of the then unfashionable Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith (London), known locally as the “old Blood-and-Flea-Pit”. He needed a new project, and some singers, and Austin and his Beecham colleagues needed new jobs, so it was a marriage made in heaven.

The music

Although Pepusch had added harmony and scored the work for the theatre, it was Gay, who had a “good ear” and was a flautist, who chose the “tunes” to be used. He fitted his own lyrics to some of the most popular songs of the day, which were mainly of English, Scottish, Irish, Italian and French origin, and they mostly came from Thomas D’Urfey’s Wit and Mirth, or Pills to Purge Melancholy, published in 1719. Although Pepusch had added harmony and scored the work for the theatre, it was Gay, who had a “good ear” and was a flautist, who chose the “tunes” to be used. He fitted his own lyrics to some of the most popular songs of the day, which were mainly of English, Scottish, Irish, Italian and French origin, and they mostly came from Thomas D’Urfey’s Wit and Mirth, or Pills to Purge Melancholy, published in 1719.

Nellie Chaplin, writing in Music and Letters in July 1922:

The unprecedented success of the Beggar’s Opera is due to the old tunes, which are in our blood. Clever as Mr. Gay’s libretto is, if Dr. Pepusch had written the “tunes” it would not have had the same hold on the public.

And Austin certainly agreed with her, as he discarded Pepusch’s work completely and used the tunes as raw material for what is, in effect, a new work made on the general plan of the old one … while keeping the atmosphere of the play and the period … turning solos into duets or more extended concerted pieces, inserting dances, instrumental interludes, and so on.

Austin himself couldn’t, quite, stop singing and he took the role of Peachum, for some time.

Nevertheless, the Musical Times review published in July, 1920 said that “the revival is thoroughly respectful to this intriguing old opera …” even though Arnold Bennett had extensively revised and bowdlerized the text, and the musical arrangement was brand new!

Nellie and her sisters

Frederic Austin:

It occurred to me also that it would be interesting to use the harpsichord and the “gamboys” [sic: gambas] … and I remembered those indefatigable propagandists of ancient music, the Misses Chaplin. They duly became the nucleus of the Hammersmith [ladies’] orchestra.

The Chaplin Trio, consisting of Nellie, Kate and Mabel Chaplin, had established themselves as a pre-eminent ladies’ ensemble, a well-known “brand”, playing both conventional classical repertoire and, from 1904, “ancient music and dances”, on authentic instruments. (Search on “Chaplin” to these previous blog posts in this series).

According to Playfair, writing in The Story of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith:

Nellie Chaplin and her sisters, and the orchestra, worked with us; for it is to be noted that from the first conception of the production to the first performance there was only possible an interval of five weeks!

[The Chaplins’] popularity with our audiences was unbounded, and a tribute, I am sure, to the great work which they have done for many years past in keeping up interest in our beautiful old English music.

The members of the Hammersmith Ladies’ Orchestra:

Nellie Chaplin harpsichord

Kate Chaplin 1st violin & viola d’amore

Mabel Chaplin cello & viola da gamba

Kathleen Thomas 2nd violin

Leila Bull oboe

Florence Mukle flute

Lilian Mukle viola

Louise Mukle double bass

We know nothing of Kathleen Thomas, except that she was described in the Tablet as being “a very capable young student of the Royal Academy, [who] gave her first violin recital at the Queen’s Hall …” But there’s a whole article (in German) about Leila Bull, whom the Musical Times noted as having “praiseworthy skill and intelligence”.

Florence, Louise, and Lilian Mukle were three of the five musical daughters of Ann Ford Mukle, a concert pianist, and Leopold Mukle, a German clockmaker from the Black Forest who was the inventor of the world’s first coin-operated juke-box, the Orchestrion.

An eighteenth-century blockbuster

The production was an instant success, due to the “tunes”, the quality of the singing, the humour (much needed, just 18 months after the Armistice) and the spare, evocative design, with just a “hint at the eighteenth-century” (due to financial constraints), which The Spectator described as “ a perfect little Hogarth [engraving]. Mr. [Claud] Lovat Fraser’s costumes and setting are beyond praise”. The production was an instant success, due to the “tunes”, the quality of the singing, the humour (much needed, just 18 months after the Armistice) and the spare, evocative design, with just a “hint at the eighteenth-century” (due to financial constraints), which The Spectator described as “ a perfect little Hogarth [engraving]. Mr. [Claud] Lovat Fraser’s costumes and setting are beyond praise”.

According to Jeremy Barlow, who has done extensive research on the The Beggar’s Opera and made his own “authentic” edition, published by OUP (realizing Pepusch’s “ungainly basses”), Austin’s version was the most popular of the 20th century. He goes on to say that the use of of harpsichord, viola d’ amore, and viola da gamba was “quite novel in the 1920s, and must have given the work a convincing period flavour at the time. Austin’s arrangement now has its own period charm, evoking musical comedy of the 1920s rather than ballad opera in the 18th century.”

At the end of the first record-breaking run of 1463 consecutive performances (which lasted for three and a half years, ending on 17 December 1923), the production had provided “a fortune” for the theatre, and had been seen by almost three quarters of a million people!

The popularity of the production was such that gramophone records, featuring members of the original cast, and the Chaplin sisters, were produced in 1922. Figurines in porcelain and wax of the main characters were also made in large numbers, including a series by the famous factory, Royal Doulton. The subsequent re-runs, in 1925, 1926, 1928, 1929 and 1930, amounting to 241 performances, added a further 120,000 people to the total.

The end of the Chaplin Trio

Nellie Chaplin died on 16 April, 1930, and her pupil, Margaret Hodsdon, took over as harpsichordist of the ladies’ orchestra for the final run, from 13 May 1930 to 21 June 1930. The review in The Times, 14 May 1930 mentioned Nellie’s demise and said that “her sisters continue to play the viola d’amour [sic] and the viola da gamba.”

According to The Times, 14 November 1932:

Much of the success of the Chaplin Trio in the past was due to Miss Nellie Chaplin, whose death deprived the sisters of their leader, and to whose musicianship they owed their repertory and the special character of their performance.

Nevertheless, the sisters tried to keep the family business going, and a promotional leaflet was made called, “The late Nellie Chaplin’s Ancient Dances and Music”, announcing many musical options and introducing Margaret Hodsdon, “a pupil of the late Nellie Chaplin”, as their new harpsichordist. The fact, though, that there are only two references to her having played together with the Chaplin sisters in concerts: in October 1931 and November 1932, rather suggests that the “great big gap” Kate Chaplin had spoken of to Percy Scholes (see here) just couldn’t be filled.

After that, either the Chaplins stopped performing completely or they continued with low-level undocumented “at homes”, garden parties and school concerts, which were advertised in that leaflet. We’ll never really know for certain.

None of the sisters ever married, and they lived together all their lives, first in the parental home – until their mother died in 1910 – and then just the three of them, with a live-in servant and a “boarder”. Kate and Mabel spent their latter years, from 1939, in Finchley, north London, with their widowed brother Charles Albert, and his daughter, Dorothy (a dancer, who had sometimes performed with them). Kate died in 1948 and Mabel passed away, aged 90, in 1960; she kept her Barak Norman bass viol with her till the very end.

In his obituary in The Strad, Nellie’s friend, the Belgian cellist, musicologist and writer, Edmund van der Straeten, wrote that “the laurel and ivy will entwine her name in the history of British musicians”. Sadly, this never happened, and Nellie and her sisters were, until very recently, completely forgotten.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Jeremy Barlow, who first mentioned the Chaplin sisters to Semibrevity; Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation; Professor Freia Hoffmann of the Sophie Drinker Institut in Bremen, who kindly shared her very extensive research; Sandy Mitchell; and Michael Mullen and Elizabeth Wells of the Royal College of Music.

Ambrose Gauntlett c. 1910, by kind permission of David Lea-Wilson © 2017 Although Ambrose Gauntlett (1889–1978) spent most of his career as a full-time orchestral principal, he was the most sought-after continuo cellist and gamba player in the UK for many years. In his obituary, published in The Times, Sir Anthony Lewis mentions “his beautiful playing of the important 18th-century viola da gamba obbligato roles”.

Ambrose was the fifth of ten children and began playing the cello at the age of six. Unusually, he only ever had one teacher, the Belgian Joseph Ernest de Munck, who stayed with him throughout his time as a junior at the Guildhall School of Music, and during his three-year scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music, starting in 1910.

Orchestral highlights

During his first year as a student at the RAM, he joined Sir Thomas Beecham’s opera orchestra at Covent Garden. In 1912 he played in the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra under Henry Wood, and for Oscar Hammerstein’s opera season at the New London Opera House as well as for Diaghilev’s Russian Ballet. In 1913 he became principal cellist of the Covent Garden Opera orchestra under Hamilton Harty and stayed there until 1929, apart from the war years.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

In 1930 he became a founder member of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, as principal under Sir Adrian Boult; he remained in this post until 1947 when, aged 58, he left to go freelance and became professor of cello at the RAM, a post from which he did not retire until he was 75, in 1965.

Early music on BBC radio

Despite his orchestral commitments (which were many more than those mentioned above), Ambrose had started playing on the radio in 1925, as a soloist and in chamber music, largely as part of the Kutcher and Mangeot string quartets.

His first documented foray into early music was in February 1927, when he played the bass part in a series of five radio programmes of Corelli’s violin sonatas with William Primrose, who was later to become famous as a viola player. The edition used was from 1780; according to the programme notes, “This bass part could either be put into shape [using the figuring] by a Harpsichord player or (as we shall hear it this week) by a ‘Cellist.”

He next appears in a broadcast in June 1929 in Bach’s cantata Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden, with the Wireless Choir and Orchestra, playing the violoncello piccolo.

The viola da gamba

Ambrose is first listed as playing the gamba in a radio broadcast of “light classical music” in October 1932, with a group called the English Harpsichord Trio. His good friend James Lockyer, who was the viola player from the Kutcher String Quartet, played the viola d’amore in that performance, with John Ticehurst on the harpsichord.

The 1678 Thomas Cole bass viol, by kind permission of the Newberry Library, Chicago © 2017 It’s interesting to note that this was exactly the same combination of instruments for which the Chaplin sisters had become famous. Perhaps following the demise of the Chaplin Trio in 1930, Ambrose saw a gap in the market?

We don’t know why Ambrose took up the gamba; he may have been inspired by hearing Rudolph Dolmetsch (1906–1942), the most talented of Arnold’s children, play the gamba in a radio broadcast in May 1931 of Bach’s cantata Tritt auf die Glaubensbahn, in which he took part, albeit on the cello.

More concerts and broadcasts

Ambrose played early music throughout his very long career, and took part in various ad hoc ensembles and orchestras, with the likes of Desmond Dupré, Charles Spinks, Thurston Dart, Diana Poulton, Julian Bream, Francis Baines, Geraint Jones, Arnold Goldsbrough and Boris Ord.

According to music journalist and author Margaret Campbell, he played in the St Matthew Passion at Westminster Abbey every year for 50 years and for the (London) Bach Choir for more than 30 years; in March 1941 the critic of The Times wrote that Ambrose’s gamba obbligato “must be specially mentioned”.

Apart from Bach’s Passions, he played Bach cantatas with the Geraint Jones Orchestra; Handel opera excerpts with the Boyd Neel Orchestra under Anthony Lewis; Monteverdi’s madrigals, with the Deller Consort. He took the gamba part, at Morley College, in Monteverdi’s 1610 Vespers in 1946 (first British performance) and 1947 and, in 1948, played in L’Incoronazione di Poppea, all of which were conducted by Walter Goehr, with a choir trained by Michael Tippett. He repeated the 1610 Vespers at the Royal Festival Hall in October 1958, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, hopefully pared down!

On radio, he played the gamba in Purcell’s King Arthur in December 1936 and was involved in several long-running radio series such as “From Plainsong to Purcell”, Gerald Abraham’s “A History in Sound of European Music” and “The Contemporaries of Bach and Handel”.

The London Harpsichord Ensemble c. 1950; FLTR Millicent Silver, Peter Mountain, John Francis and Ambrose Gauntlett, by kind permission of Sarah Francis © 2017 From 1948 he performed in more than a hundred radio programmes with the London Harpsichord Ensemble, run by the husband-and-wife team of John Francis (flute) and Millicent Silver (harpsichord), which consisted of several musicians in many different combinations. Although Ambrose played Bach’s gamba sonatas with Millicent Silver in November 1950, most of the ensemble’s repertoire consisted of trio sonatas, solo cantatas and small chamber works by Couperin, Rameau, Buxtehude, Purcell and so on.

Ambrose was a member of the Elizabethan Consort of Viols, founded in 1957 by Dennis Nesbitt (who was also a principal cellist, of the London Symphony Orchestra). Late in his career, he played with the Purcell Consort of Voices, James Bowman (counter-tenor), and Robert Spencer (lute).

Ambrose continued playing until May 1972, when he was 82; his last concert performance was at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, in an orchestra formed to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Royal Academy of Music.

Recordings

Apart from his lifelong work with various orchestras, Ambrose began recording in 1924 with two records of the songs of M. A. Lucas, with Gladys Marloe and James Lockyer, viola. In 1934 he played the gamba in Purcell’s Golden Sonata with Isolde Menges and William Primrose, violins, and John Ticehurst, harpsichord.

Listen to this recording of Purcell’s Golden Sonata

Ambrose played the obbligato gamba in both the 1948 recording of the St Matthew Passion and the 1952 St John Passion, with the Bach Choir and the London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Sir Adrian Boult.

Listen to Ambrose and Kathleen Ferrier in Est ist vollbracht, from the St John Passion, sung in English as It is fulfilled.

Compare this with Harnoncourt’s 1985 version, with a boy alto and Christophe Coin

Ambrose with Yehudi Menuhin and George Malcolm c. 1960 Ambrose played the gamba in three of Bach’s six Sonatas for Violin and Harpsichord recorded by Yehudi Menuhin and George Malcolm in 1962; he also took part in Menuhin’s version of Handel’s Op. 1 Violin Sonatas, the Water Music and Bach’s sixth Brandenburg Concerto. He played with Malcolm again in the Bach Flute Sonatas, with Elaine Shaffer, and subsequently made discs of songs with Janet Baker and John Shirley-Quirk.

Instruments

Until 1958, Ambrose owned a 1693 Barak Norman bass viol, which he sold to Dietrich Kessler; this instrument (inventory number 937) is now part of the Kessler Collection at the Royal College of Music Museum.

The 1693 Barak Norman bass viol, by kind permission of the Royal College of Music Museum © 2017. He kept a 1678 Thomas Cole bass viol until his death, which is now owned by the Newberry Library in Chicago, and used by the Newberry Consort. He also had an undated Barak Norman cello and, at least, another one, by Goffriller (date unknown).

Significance

As with his BBC Symphony Orchestra colleague, Harry Danks (of the London Consort of Viols), playing the gamba and early music in general was only ever a sideline. Nevertheless, Ambrose was described in the obituary in The Musical Times as “a leading exponent [of the viola da gamba], at a time when the instrument was rarely used”; certainly he was one of the very few people who could play the instrument at a professional level, rather than simply being able to hold a part in a consort.

And although he initially set up his gamba with a very high bridge and without frets, and bowed it like a cello – which led Robert Donington to call the instrument a “cellamba”, and comment that Ambrose played “with a musicianship worthy of a better cause” – he was not the only one to do this.

According to John Rutledge, in his articles in the Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society of America, this practice was widespread from the 1880s to the 1950s at least. In fact, Ambrose was in very good company, as the Dutch early music pioneer, Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp (1906–2000), who taught Anner Bylsma and Gustav Leonhardt, bowed overhand on a seven-string gamba with an end-pin, which had been specially made for him by the Amsterdam violin maker Max Möller, so as to produce a very big sound.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s approach was also not always very authentic, as he mentioned in an interview in 2012, speaking about his involvement, with Leonhardt, in Straube’s film Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach which was released in 1967. Harnoncourt, who had started the gamba in the late 1940s, said, “I […] immediately changed my way of playing on the gamba for this film, because at that time I held the bow from above, and of course for the film, for historical reasons, I had to hold the bow from underneath, which is how they played in the period.”

Ambrose in later life, playing an unidentified gamba. The eminent viol player, Jane Ryan, first heard Ambrose when she was a schoolgirl, at one of the annual Bach Choir performances of the St Matthew Passion, with the Jacques Orchestra, at the Royal Albert Hall after the war, and she still remembers the very beautiful hybrid sound that he made then.

In later years, she got to know Ambrose well and performed with him. She told me that he became more historically informed after playing with Dennis Nesbitt in his Elizabethan Consort of Viols, and she thought that he may even have read Christopher Simpson’s 1659 book The Division Viol.

Acknowledgments

“First Chair Soloists”, an article in The Strad written by Dolmetsch biographer, the late Margaret Campbell, has been an important source. Thanks are due to Nick Cutts and Katharine Richman of the Bach Choir; David Douglass of the Newberry Consort; Sarah Francis; David Lea-Wilson (Ambrose’s grandson) and his family; Thomas MacCracken; Gabriele Rossi Rognoni, Curator, Royal College of Music Museum, and Jane Ryan.

Copyright © 2017 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

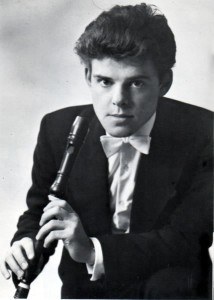

An early publicity photo Guest Blogger: Peter Dickinson is a composer, writer and pianist and an Emeritus Professor of two universities – Keele and London. See here for more details.

‘My wife and I first met David and Gill Munrow in Cambridge in about 1965. It was summer and we were all in the garden at 54 Bateman Street, the home of Mary Potts, whose late husband was L. J. Potts, the literary critic and English don at Queens’ College.

Mary Potts had a very special role in the early music revival which has not been acknowledged [other than in this Semibrevity blog post]. A mere mention of her more distinguished pupils, who included Christopher Hogwood, Colin Tilney and Peter Williams, is enough to indicate that she ought to be better known now. She knew harpsichordists of international reputation such as Gustav Leonhardt, Raphael Puyana and Kenneth Gilbert. Her own performances were on a more modest scale but she played in and around Cambridge for over fifty years. At May Week concerts she was especially busy taking her harpsichord round various colleges. She became a focus for early music activities long before David Munrow propelled these into a new public orbit through his recitals, lectures and broadcasts. Her influence could perhaps be seen as complementary to that of Thurston Dart in the official Cambridge University Music Faculty.

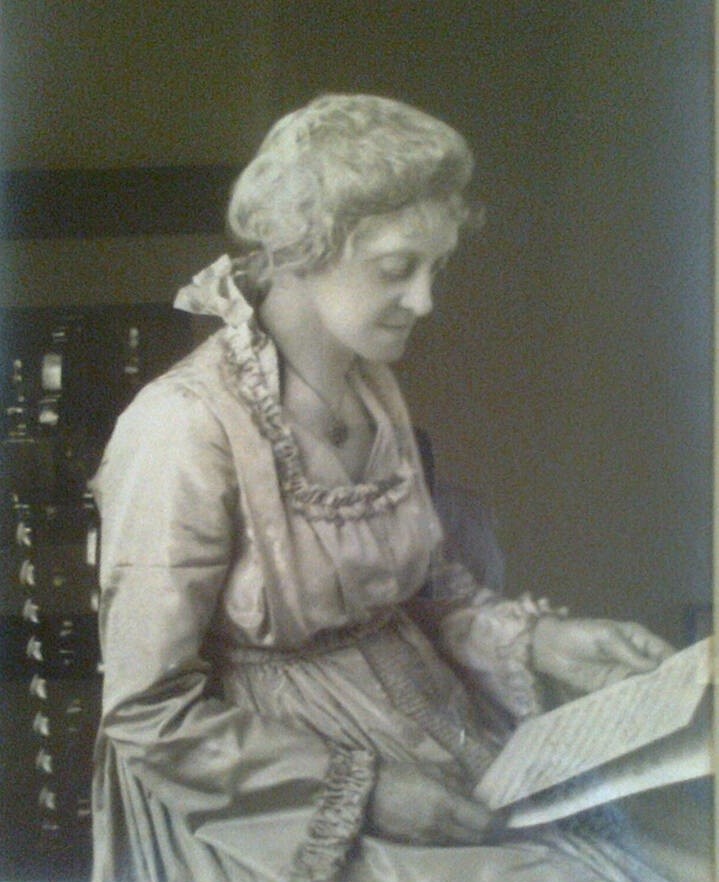

Mary Potts at her beloved Shudi harpsichord in about 1950 © Estate of Mary Potts 2017 Mary Potts was born in 1905 and studied at the Royal College of Music from 1923-28 as a pianist but also took harpsichord lessons with Arnold Dolmetsch and was a regular visitor to Haslemere for some years. When she married L. J. Potts she moved to Cambridge in 1930. Her own harpsichord was made in the eighteenth-century by the Swiss-Englishman Burkat Shudi (1702-73): it was bought from Dolmetsch, and some of the first rehearsals of Munrow’s Early Music Consort took place in her music room. She died in 1982 and will long be remembered for her generous and sympathetic encouragement of younger musicians.

Mary Potts was not just involved with the [music of the] past. She encouraged young composers too and I wrote my Variations on a French Folk Tune for her. (Recorded by Jane Chapman, a Potts pupil, on Heritage HTGCD 259)

She gave the first performance at the University Music Club in 1957 and also played the keyboard part in my Quintet for flute, clarinet, violin, cello and harpsichord (now destroyed). This kind of activity makes a productive link with David Munrow who also believed that early music instruments were not just archaic survivals but needed new repertoire.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

My next contact with Munrow was in connection with my chamber piece he had commissioned called Translations for recorder, gamba (Oliver Brookes) and harpsichord (Christopher Hogwood). The trio was known as the Early Music Consort of London and gave the premiere at the Purcell Room on 20 February 1971. At the time there were very few British works that used multi-phonics for the recorder so we worked out what was possible. I also worked with Oliver Brookes on the use of twentieth-century techniques applied to the viola da gamba. For early music players some of Translations was distinctly innovative – that was the reason for the title. Unfortunately they never recorded it. However, John Turner later gave several performances with Oliver Brookes and Keith Elcombe.

Just over a year after Translations later David commissioned a solo piece – Recorder Music. At this period he was becoming widely known for one of the liveliest programmes broadcast on BBC Radio 3 – Pied Piper, which ran from 1971-76 with over 600 episodes. In addition to all his concert work, lectures and teaching he researched and presented this weekly programme, putting not only himself but his skilled producer the late Arthur Johnson under enormous pressure. (See Peter Dickinson, Arthur Johnson, obituary, The Guardian, 11 December 2014)

Since Munrow went around recording interviews with people I thought it would be perfectly natural for him to come onto the stage, switch on his portable tape-recorder and proceed to perform alongside it. So that was the basis of Recorder Music. I again used a range of material, including multi-phonics, and incorporated my Air for solo flute (1959). (Recorded by Duke Dobing on Naxos 8.572287) I adapted this melody for an instrument David had brought back from his travels in Peru – a notch flute called the kena. Then, knowing what a startling impression this would give in a live performance, I included a march for David to play on two recorders at once – the garkleinflötlein and the sopranino. This comes back at the end but with the much larger tenor and bass recorders together – even more of a mouthful. The live performer is without tape for a central cadenza, which is alarmingly difficult. David arrived at our house one day saying that he’d been practising it for nine hours.

He gave the first performance of Recorder Music on 8 February 1973 at the Wigmore Hall. However, it seemed more satisfactory to have good quality tape-playback rather than a portable machine and this made the whole business inconvenient and expensive. The best medium for this kind of piece is a recording or a broadcast and so David recorded Recorder Music for EMI and it came out in 1975 at the end of his two-LP survey called The Art of the Recorder. (EMI SLS 5022; now on CD with Testament SBT2-1368) I wrote a memorial tribute for a BBC concert in Manchester on 7 May 1977, at which Munrow was to have played Recorder Music. A Memory of David Munrow is for two counter-tenors, two recorders, gamba and harpsichord, using only material from the two pieces I wrote for him.

My last professional connection with David was the strangest of all. He was involved with music for a science-fiction film written, produced and directed by John Boorman – Zardoz (1974), which became famous for the role played by Sean Connery, and still goes the rounds. (On DVD Twentieth-Century Fox, F1-SGB 01208DVD (1974) The name comes from The Wizard of Oz and the film is set in the year 2293.

Apart from the Allegretto of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony in various arrangements, David must have provided choral textures with tone-clusters as anguished support for some scenes of conflict. One day David telephoned me and the conversation ran something like this:

‘We’re doing this music for Zardoz and John Boorman is a bit short of some spectacular sounds for a chariot swooping down from outer space. I said that you could improvise this if he booked a big organ in a city church. It’s fixed for tomorrow morning – can you come?’

Luckily I could and when I got to St Andrews, Holborn, on 19 October 1973, Boorman was there with all the technical people set up to record the organ. He told me what was going on in the film – he needed music for the space-ship and associated supernatural elements. We tried various things out. When he liked what I played it was recorded – all in a morning. It seemed to be the easiest way to do film music – and the easiest money too.

The last time I spoke to David was on the telephone in 1976. It was in my second year at Keele University, where I had started the Music Department as the first Professor. David said he was concerned to find – most unusually – a two-week gap in the concert schedule for the Early Music Consort in the coming year and wondered if I could help. I can’t now remember what I said, but I’m sure I was encouraging; it was May and I spoke to him looking out over the apple trees in blossom in our garden in Keele village. Two weeks later he was dead and I heard the shocked voice of Christopher Hogwood in a BBC Radio 3 tribute – but what a truly astonishing legacy from such a short, high-voltage career.

This is an edited extract from Peter Dickinson: Words and Music, which was published in 2016 by Boydell & Brewer.

Copyright © 2017 Peter Dickinson – All Rights Reserved

Also of interest:

Huguette Dreyfus at home in the early 1960s, playing her Blanchet. From a private collection, all rights reserved. Guest blogger:

Sally Gordon-Mark, writer/researcher/translator/teacher, was a student and devoted friend of Huguette.

November 30th would have been Huguette Dreyfus’ 88th birthday, but the effervescent concert artist and beloved teacher, the self-proclaimed “inexhaustible chatterbox,” silently slipped away near midnight on May 16, 2016.

It had become customary for organists and harpsichordists to come from all over the world to study with her, Kenneth Gilbert or Gustav Leonhardt. Able to converse with her international students in English, German, French and Italian, she had an enormous gift and love for teaching. She once said her students didn’t need her as much as she needed them.

Listen to Huguette Dreyfus playing Bach’s Concerto No. 3 in d (after Marcello) BWV 974

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

Pauline Huguette was born in Mulhouse (Alsace, France), November 30, 1928 to Fernand and Marguerite Dreyfus. At age 4, she began piano lessons. With her cousin Nicole (later a famous lawyer), and also her older brother Pierre, she played duets and improvised, still a child. Her family was well off, her father an industrialist with factories in Mulhouse and Vichy.

On September 3, 1939, WWII was declared and Jewish families were evacuated from the Alsace region. Fernand took his family to Vichy where he had business interests and friends. Dreyfus enrolled in the Clermont-Ferrand conservatory under a pseudonym, finishing her studies with a first prize in piano. She must have taken on students then, as she said later that she had started teaching at age 14.

In August 1942, the French government turned over more than 6500 Jewish adults and children living in the unoccupied zone to the Nazis; in December, Huguette, her father and brother escaped into Switzerland, according to Swiss records. They settled in Geneva where they had relatives. In 1944 Huguette crossed the border again, apparently alone.

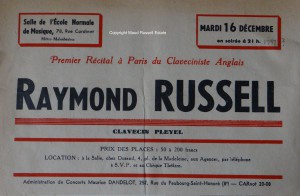

In 1946, Dreyfus and her brother Pierre moved to Paris. At the Ecole normale de Paris, Huguette studied with the great pianist, Lazare-Levy, whose manner of teaching was considered innovative and original with respect to technique, fingering and interpretation.

In 1948, their parents joined her and Pierre. The next year, her father bought a large apartment for the family on Quai d’Orsay near Pont Alma. Huguette would remain there until her death. She studied at the Paris Conservatory for four years, profiting enormously from her class in musical aesthetics with Roland-Manuel, critic and film composer. He had a weekly live radio program on which she often performed.

Dreyfus also felt the same respect and admiration for her music history professor, Norbert Dufourcq – musician, author and lecturer. Dufourcq devoted the year of 1949-50 to the music of Bach, and Huguette’s life changed for good. Dufourcq had managed to procure a small Pleyel; it was the first harpsichord Huguette ever played and a revelation to her.

In 1949, Dufourcq asked Jacqueline Masson, another of his students, to give a harpsichord class, which she did until 1955. Huguette took that class, at least for a year, since it is noted in Conservatory records that on June 6, 1951, she passed the examination with her rendition of Bach’s Toccata, BWV 910.

In 1953, Jacqueline Masson, studying with Landowska’s favorite pupil, Ruggero Gerlin, in Italy, recommended him to Huguette. She and a friend, Anne-Marie Beckensteiner, enrolled in his class and set off for Siena in July 1953, Huguette having won the first of three scholarships from the Academia Chigiana.

Count Chigiani-Seracini established the Accademia in his palazzo in Siena, offering concerts and master-classes from July 15th to September 15th by famous musicians like Andres Segovia and composers like Georges Enesco, whose classes Huguette audited. Every night there were public concerts in the palazzo. Gerlin’s classes were given three times a week; Huguette became his star pupil. As Anne-Marie Beckensteiner remembers, he had her illustrate how to make the music sing, continually praising her hand positions. For Dreyfus, it was a rich, delightful experience and she returned five more summers, giving a total of seven concerts. She later spoke of Gerlin as her only harpsichord teacher.

During this period, her brother gave her a harpsichord built by Nicolas Blanchet, c. 1715, purchased in a shop on Rue Royale in Paris. Because there are few in existence, the American builder William Dowd, a pioneer himself, came to her home to examine it. Contemporary harpsichords were not comparable to historic ones, making the playing experience quite different. Huguette said she learned much about the interpretation of early music from the touch of her instrument.

Huguette Dreyfus, c. 1960 For an aspiring concert artist, the early music scene was daunting. Music had to be sought in archives; the urtext editions easily available today didn’t exist then. Concert opportunities were few because of the paucity of harpsichords. The first post-war harpsichordists to appear in France were Aimée van de Wiele (on Huguette’s jury in 1951), Marguerite Roesgen-Champion, Marcelle Charbonnier and Pauline Aubert. Jeanne Chomet travelled around France in a van, introducing the harpsichord in places it had never been heard before.

Finalist in the harpsichord competition at the Concours d’exécution musicale in Geneva in October, 1958, Huguette made the daring choice to add pieces from Bartok’s “Mikrokosmos” to her program, having been the first to discover that Bartok intended some pieces to be played on the harpsichord. Her exposure at the Concours launched Huguette’s career; shortly afterwards, she gave her first concert, in Paris, performing sonatas by Scarlatti, whose music she described as “life itself.”

Listen to Huguette Dreyfus playing Scarlatti sonatas

//www.youtube.com/watch?v=rfKw6keEsmk&list=RDrfKw6keEsmk#t=71

Dreyfus’ mentor Roland-Manuel and others spoke about her to Michel Bernstein, owner of the French label, Valois. He had never heard a historic harpsichord before, and when she played her Blanchet for him, he was absolutely dazzled and signed her to a contract. Her first recording was a three-album set of Rameau’s solo harpsichord pieces, not performed since a concert given by Louis-Josèph Diémer at the Paris World Fair in 1889. In 1963, she went abroad for the first time, on a three-week tour of the United States with the Paul Kuentz orchestra.

In the early ’60s, she met harpsichord builder Claude Mercier-Ythier, owner of a harpsichord signed Henri Hemsch (1754). It became Huguette’s favorite instrument and was used whenever possible for her recordings and concerts. They would enjoy a close professional relationship and friendship that would last over 50 years – “a beautiful adventure” he remembers.

Listen to Huguette Dreyfus playing François Couperin – Treizième ordre

In 1963, Dr Pierre Rochas founded the Académie d’Eté at Saint-Maximin-La Sainte-Baume, its Basilique housing a very famous 18th-century organ. It was Mercier who proposed that Huguette give a concert-conference there. It was so successful that the following year, early music classes were organized and something new: concerts from noon to midnight. Among the invited professors was Eduard Melkus, with whom she would record and give concerts, for the next 45 years. Melkus too was in the forefront of the early music revival, dedicating himself to authentic interpretation. He played with Gustav Leonhardt and Nicolas Harnoncourt in Vienna in the 1950s.

Huguette Dreyfus and Eduard Melkus, 2008, with the kind permission of Eduard Melkus. Melkus and Huguette met for the first time at St. Maximin. They soon ended up improvising together, creating a complicity “from the first moment” that would continue until their last concert together in 2008. Melkus recalls:

“She was an excellent musician and highly regarded by other musicians. Henryk Szeryng had played with Robert Veyron-Lacroix, but once he played with Huguette, he would never play with any harpsichordist but her. She was the best harpsichordist in France.”

Listen to Henryk Szeryng and Huguette Dreyfus playing Corelli’s “La Folia”

From 1967 to 1990, Huguette taught at the Schola Cantorum in Paris. One of her students was Christophe Rousset, who took his lessons in her home. He dedicated his recently-published biography of François Couperin – “La muse victorieuse” – to Huguette, with whom he was very close.

In 1970, Dreyfus and Valois parted company, when Archiv Produktion invited her to record Bach’s English and French Suites. She would later record for Erato, Deutsche Grammophon-Polydor, Philips, Harmonia Mundi, Barenreiter-Musicaphon, Musifrance, Critère and Denon-Nippon Columbia.

From 1971 until 1982, she taught at the Ecole nationale de musique de Bobigny, where Elisabeth Joyé was in her class, and the Institut de musicologie de Paris-Sorbonne. Then from 1982 to 1994, she worked at the National Superior Conservatories of the Regions of Lyon and of Rueil-Malmaison. Jory Vinikour and Olivier Baumont studied with her in Rueil.

As Jory wrote in a tribute to her soon after her demise:

Although inquisitive and informed on questions of performance practice, she never permitted theory to displace basic mastery of the instrument, stressing phrasing, expressivity, clearly defined polyphony. Less arcane problems were handled with great simplicity – those of us treated to having our hair pulled sharply upwards invariably saw improvement in our postures!

Blandine Verlet, Béatrice Martin, Ilton Wjuniski, Noëlle Spieth, Yannick le Gaillard, Jocelyn Cuiller, Laure Morabito and Yasuko Uyama-Bouvard also studied with Huguette. Many of her professional students continued to play for her before concerts, tours and recording sessions, and most students maintained friendships with the quick-witted, warm-hearted and humorous Huguette.

Every year from 1983 to 1993, and then biannually until 2008, Huguette gave master-classes at the Académie musicale de Villecroze. She continued to give concerts and record CDs. Conrad Wilson, a Scottish music critic, reviewed her performance in Edinburgh (1974): “As an exponent of Rameau, she made a scintillating impression … colouring and ornamenting the music with considerable polish and allure.” A greater compliment still, Henri Dutilleux composed for Huguette an extension of his work “Citations” which she premiered at the Festival of Besançon in 1991.

On May 25, 2008, the city of Mulhouse presented Huguette with a medal in an “Hommage à Huguette Dreyfus.” Invited to give a concert for the occasion, she and Eduard Melkus played a program of music by Bach and Couperin. In November, they also performed together in Vienna. Her final concert was in Japan (2009).

Her recordings received numerous prizes: the Grand Prix du Disque de l’Académie Charles Cros (seven times), the Grand Prix de l’Académie du Disque Français (three times), the Grand Prix des Discophiles, the Prix de la Nouvelle Académie du Disque, and the Prix du Président de la République.

The French government also bestowed honors on Huguette: in 1973, she was declared Officier de l’Ordre national de mérite; on March 4, 1996, Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur and December 14, 2008, she was promoted to Officier de la Légion d’Honneur. In Austria, she received the title: Officer of Arts and Letters and of Merit of the Austrian Republique.

From 1958 to 2009, she gave concerts in Europe, the U.K., North and South America, Asia, and South Africa. In France, she played in festivals and appeared regularly on radio and television. In January 1997, Huguette performed at the Théatre Grévin in Paris. In Le Monde, Pierre Petit wrote:

Huguette Dreyfus, imperial and faultless, recreated the desired atmosphere every time. [Bach’s The Italian Concerto:] … Dreyfus using with supreme intelligence the opposition of her two keyboards, which brought us a second movement that was particularly moving… [Scarlatti:] With unsurpassable virtuosity, Huguette Dreyfus strung together these unceasingly different pieces in a firework display of joyful and multicolored orginality. It was an absolute triumph, amply merited.

Dreyfus was featured in a 16mm documentary “Le Clavecin” and recorded the soundtracks of two short films. She gave master-classes, served on countless competition and examination juries, and participated in symposiums. Having published articles on Couperin, she also edited “The Goldberg Variations” for Wiener Urtext.

A personal photograph of the late János Sebestyén, graciously provided by Robert Tifft.

Members of the jury of the Concours International de Clavecin de Paris, 1976: FLTR: Huguette Dreyfus, Robert Veyron-Lacroix, Gustav Leonhardt, Ruggero Gerlin, Kenneth Gilbert, and in front, János Sebestyén. Her legacy was twofold. She left us a large number of rare but findable CDs and LPs

[full discography], recognized as having contributed to the popularity of the harpsichord and the French early music revival. What she imparted to her students however can never be measured.

A more detailed Complete Discography has been compiled by Sally Gordon-Mark.

Acknowledgments

For their kind participation, I thank: Anne-Marie Beckensteiner (interview); Conservatoire Emmanuel Chabrier, Clermont-Ferrand; Françoise Dreyfus (interview); Stephanie Gray, Johnston Press PLC; Eduard Melkus (interview); Claude Mercier-Ythier (interview); Miriam Pizzi, l’Accademia Chigiana; Didier Schnorhk; Robert Tifft and Frank Trnka.

Memorial concert

A memorial concert to be held on 5 May 2018, played by her former students, is being organized. If you would like to participate or attend, please contact Sally Gordon-Mark, sally.gordonmark[at]dartybox.com

Copyright © 2016 Sally Gordon-Mark – All Rights Reserved

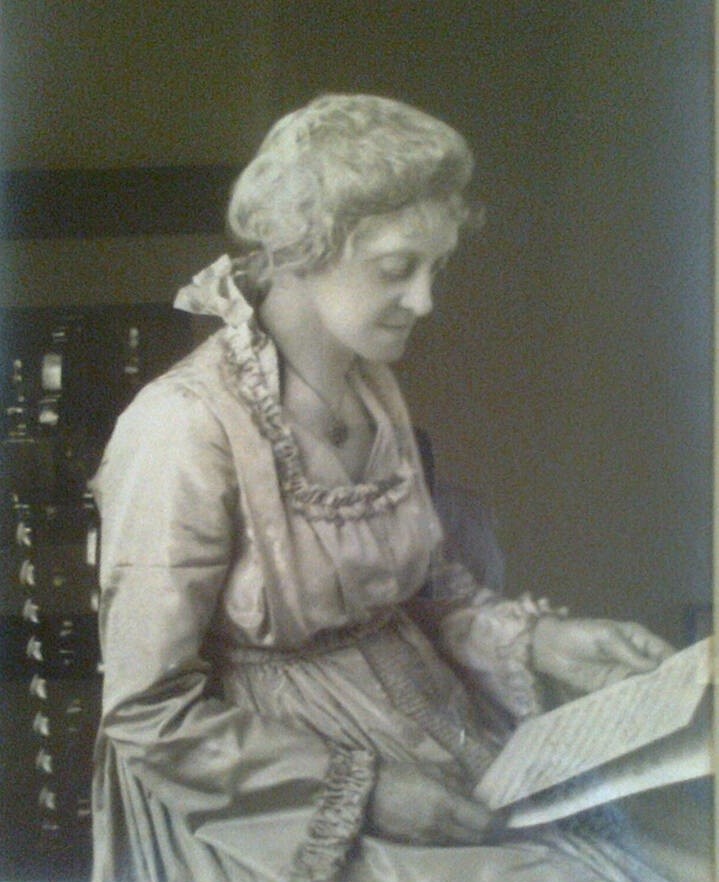

Nellie Chaplin in 1910 By Guest Blogger: Mandy Macdonald

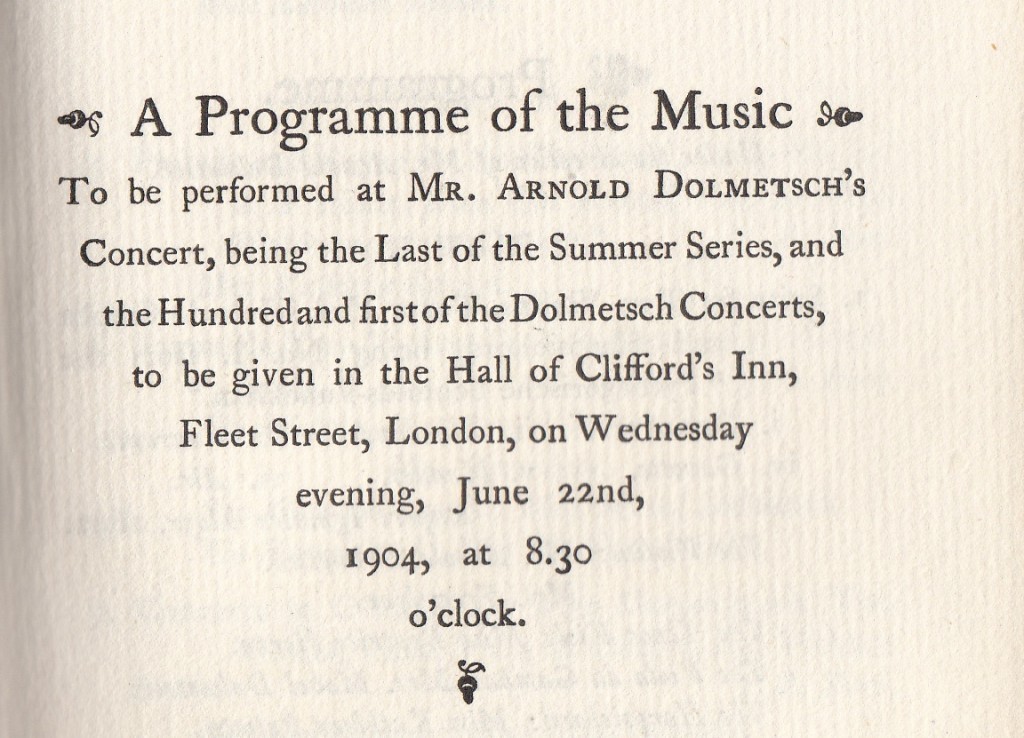

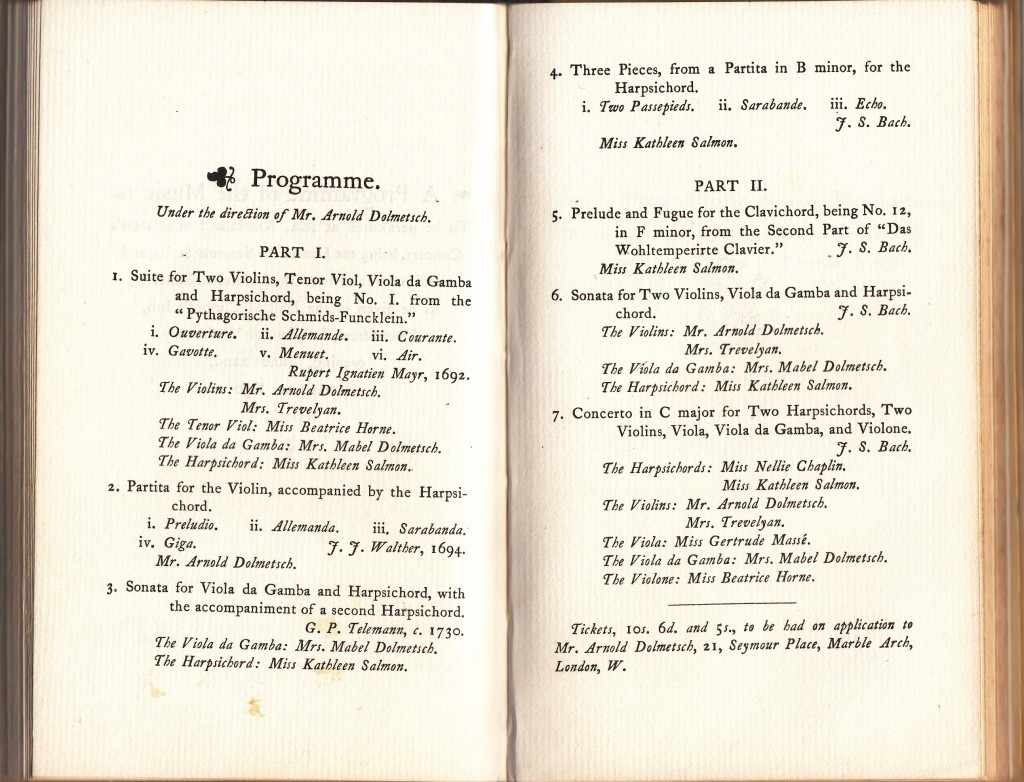

One fine morning in the summer of 1904 a van drew up at our door and from it emerged Arnold Dolmetsch and a harpsichord. He had previously asked me to play in Bach’s Double Concerto in C major with Miss [Kathleen] Salmon at one of his concerts in Clifford’s Inn. As I had no knowledge of the harpsichord, it was a case of “fools rushing in”. However, all went well at the concert as far as the ensemble was concerned, and the result was that it fired me with a desire to possess an instrument of my own.

Thus Nellie Chaplin opens a fascinating article, “The harpsichord”, which she wrote in 1922 for the journal Music and Letters (3: 3, July 1922, pp. 269–73), describing her first encounter with the harpsichord and her subsequent commitment to exploring both music and dance of the pre-Classical period.

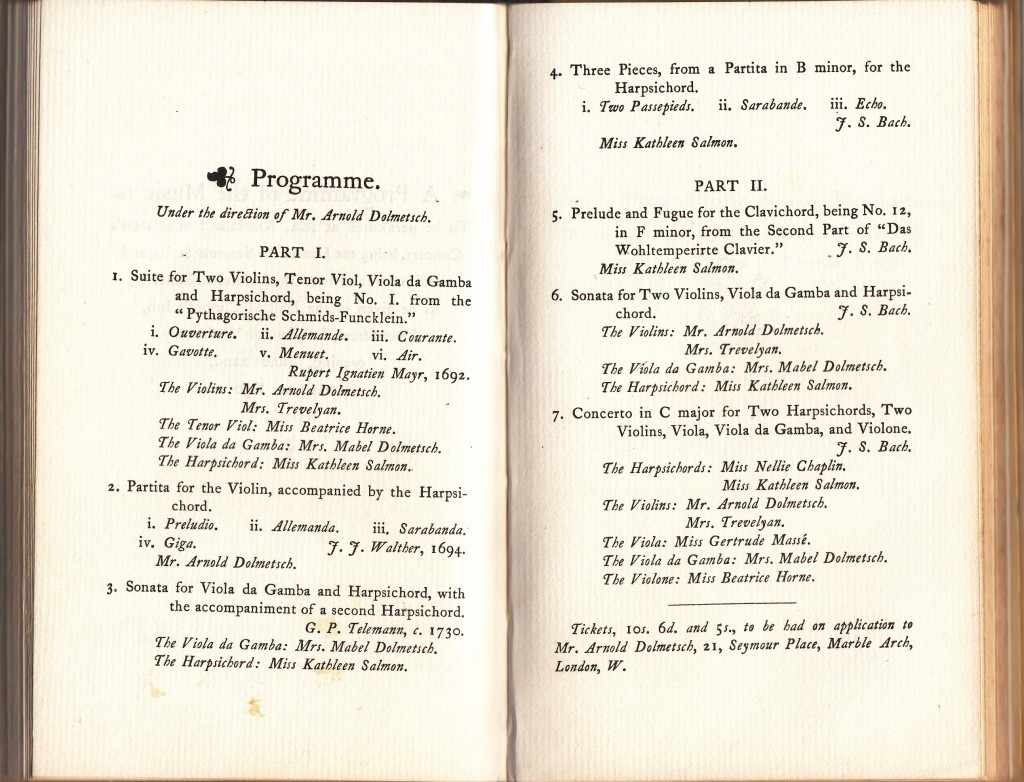

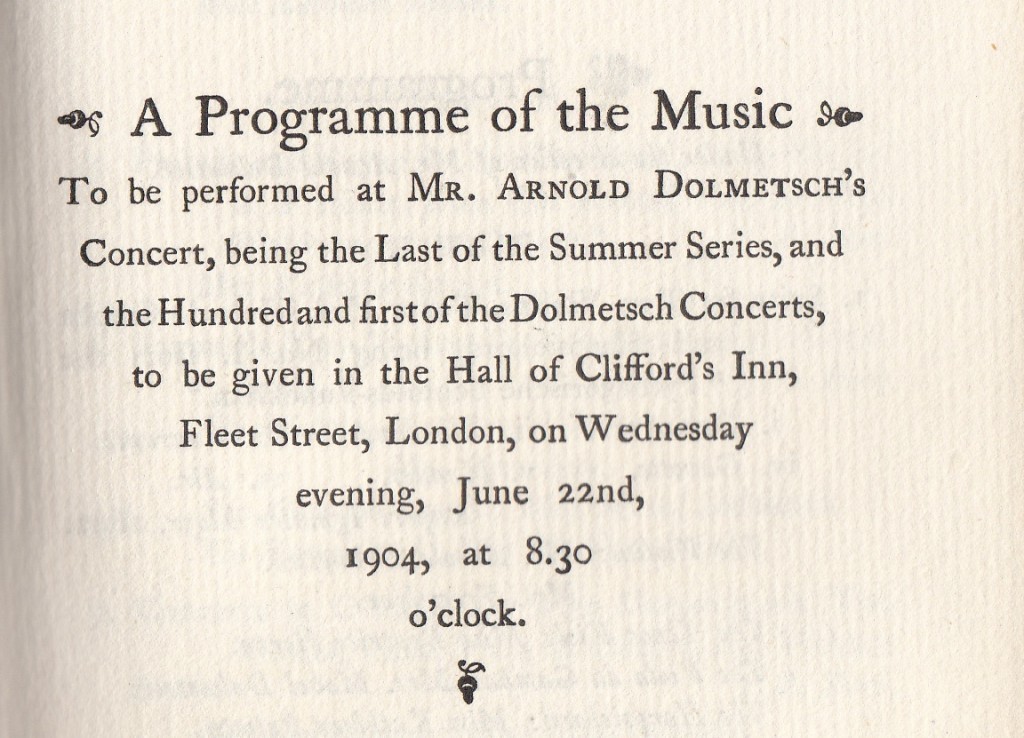

This programme (© Jeanne and Francois Dolmetsch) was, in fact, from Arnold Dolmetsch’s 101st concert given at various different locations in London, and not just at Clifford’s Inn, which was the building occupied by Arts Workers’ Guild.

She seems to have given up playing the piano in public more or less then and there in favour of the harpsichord. Although we have no evidence that she ever had a harpsichord teacher, except possibly Dolmetsch; she probably received advice and borrowed music from her friend, Nellie Milner-Taphouse (who had been performing on the harpsichord since 1894, and from whom she borrowed her first Kirkman). Her friend’s step-father, the collector T.W. Taphouse, owned some 200 volumes of early editions of harpsichord music, including Couperin’s L’art de toucher le clavecin (1717) and several other early tutors, dating back to 1593.

In any event, she says she had found useful for the harpsichord the piano technique developed by Ludwig Deppe (1828–1890), based on “weight and relaxation” of the whole arm rather than finger movement alone. By the standards of the time, she certainly became an expert in the instrument.

The arrival of the harpsichord was one of two pivotal events that caused a sudden and dramatic change in direction for Nellie and her sisters from the standard classical repertoire of their day to the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The other key event was Nellie’s discovery, about the same time, of early dance. She tells this story in another article from 1922, written for The Sackbut (vol. 3, October 1922). In autumn 1903 she played the musical illustrations (we are not told on what instrument, but we assume the piano) for a lecture-recital by J. H. Bonawitz, founder of the London Mozart Society, which traced the evolution of the dance “from the Pavane to the modern waltz”, including the allemande, courante, sarabande, and other movements of French and English suites familiar to us from the works of so many Baroque composers.