By Guest Blogger: Mandy Macdonald

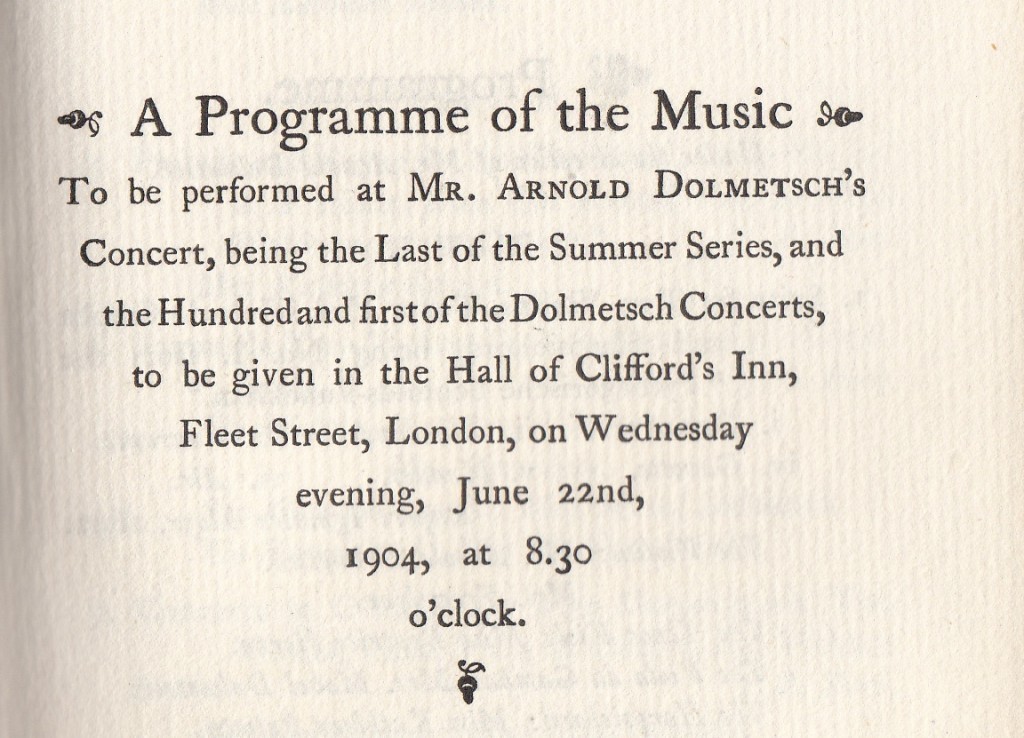

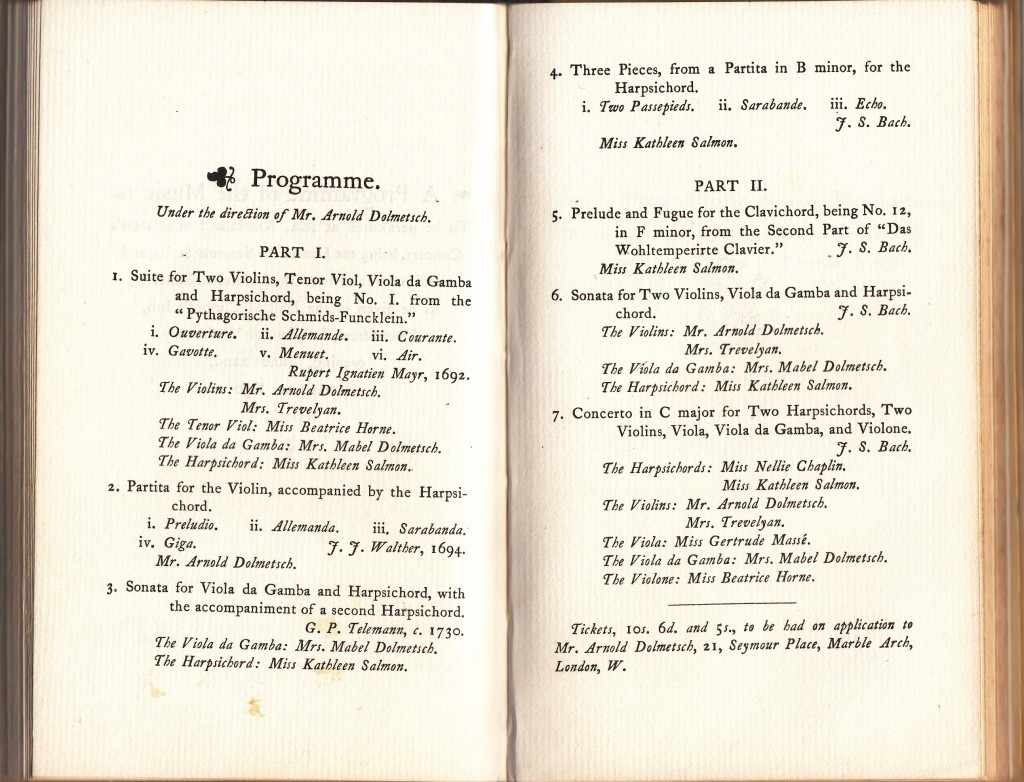

One fine morning in the summer of 1904 a van drew up at our door and from it emerged Arnold Dolmetsch and a harpsichord. He had previously asked me to play in Bach’s Double Concerto in C major with Miss [Kathleen] Salmon at one of his concerts in Clifford’s Inn. As I had no knowledge of the harpsichord, it was a case of “fools rushing in”. However, all went well at the concert as far as the ensemble was concerned, and the result was that it fired me with a desire to possess an instrument of my own.

Thus Nellie Chaplin opens a fascinating article, “The harpsichord”, which she wrote in 1922 for the journal Music and Letters (3: 3, July 1922, pp. 269–73), describing her first encounter with the harpsichord and her subsequent commitment to exploring both music and dance of the pre-Classical period.

This programme (© Jeanne and Francois Dolmetsch) was, in fact, from Arnold Dolmetsch’s 101st concert given at various different locations in London, and not just at Clifford’s Inn, which was the building occupied by Arts Workers’ Guild.

She seems to have given up playing the piano in public more or less then and there in favour of the harpsichord. Although we have no evidence that she ever had a harpsichord teacher, except possibly Dolmetsch; she probably received advice and borrowed music from her friend, Nellie Milner-Taphouse (who had been performing on the harpsichord since 1894, and from whom she borrowed her first Kirkman). Her friend’s step-father, the collector T.W. Taphouse, owned some 200 volumes of early editions of harpsichord music, including Couperin’s L’art de toucher le clavecin (1717) and several other early tutors, dating back to 1593.

In any event, she says she had found useful for the harpsichord the piano technique developed by Ludwig Deppe (1828–1890), based on “weight and relaxation” of the whole arm rather than finger movement alone. By the standards of the time, she certainly became an expert in the instrument.

The arrival of the harpsichord was one of two pivotal events that caused a sudden and dramatic change in direction for Nellie and her sisters from the standard classical repertoire of their day to the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The other key event was Nellie’s discovery, about the same time, of early dance. She tells this story in another article from 1922, written for The Sackbut (vol. 3, October 1922). In autumn 1903 she played the musical illustrations (we are not told on what instrument, but we assume the piano) for a lecture-recital by J. H. Bonawitz, founder of the London Mozart Society, which traced the evolution of the dance “from the Pavane to the modern waltz”, including the allemande, courante, sarabande, and other movements of French and English suites familiar to us from the works of so many Baroque composers.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

Reuniting the sister arts of dance and music

Nellie decided to research and reintroduce performances of “these old dances, which had such a marked influence on the development of Musical Form, from the Suite to the modern Symphony”. At the British Museum, she hunted out French dancing manuals of the 16th and 17th centuries, starting with Arbeau’s Orchésographie of 1589, and began to prepare dances for performance based on the instructions and figures in the texts. She brought on board an Italian dance teacher and choreographer, Carlo Coppi, formerly of La Scala, Milan, and working at the time at the Alhambra Theatre in London. Their first collaboration took place on 6 July 1904 in the Royal Albert Hall Theatre. Led by Nellie at the harpsichord, the sisters and some other women instrumentalists played “the Pavane and Galliard, Allemande, Courante and Sarabande, Minuet and Gavotte, with national dances, Tarantelle, Jota Aragonese, Hornpipe, Irish Jig, and Scotch [sic] Reel” – this last played by military pipers from the King’s Royal Rifle Corps – accompanying dancers in period costume.

A similar programme was given later in 1904 and repeated three times in January 1905. Broadly the same formula would be used again and again in programmes of “Ancient Music and Dances” played by the Chaplin sisters over the next quarter-century, in nearly 140 performances around the country.

The standard line-up was up to 15 dancers, mostly girls, “with occasional male assistance”, the Chaplin Trio or String Quartet, Nellie Chaplin on harpsichord, one or two wind instruments, usually oboe and flute, and a variety of singers. The instrumentalists were usually women. It is not clear to what extent they used Baroque strings and in what combination with modern strings; many of the dances were arranged for “string quartet and oboe”, but Nellie wrote in 1922 that “latterly, the Harpsichord, Viola d’amore and Gamba have been used most effectively”, and many reviews specifically mention the Baroque strings.

A winning formula

“The aim in reviving these beautiful dances of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries”, Nellie wrote, “has been to re-unite the art of ‘Dancing’ once more to the Sister Art of ‘Music’”. Reviewers and others repeatedly singled out the dancing as the distinctive and most attractive feature of the Chaplin concerts. As early as 1907, dance historian Ardern Holt dedicated his book, How to dance the revived ancient dances (London: Cox, 1907),

In London, … at Bedford, Oxford, Hereford, and Eastbourne, indeed all over the country, Miss Chaplin has initiated performances of these dances, which have been received with intense interest. The enthusiasm they have aroused should be a little reward to her for the immense pains that have been bestowed upon them … Those desiring to be further practically educated in the dances and steps should apply to her, for she is at the present moment initiating classes all over the country.

Twenty years later, a review in The Times of 31 October 1927 shows that none of the magic had gone:

These dances, which have been composed so far as possible from Arbeau, Playford, and other writers, shed a flood of light on the character of the music of the pre-classical period.

Masques and other entertainments

The combination of pretty girls dancing and music played on exotic-looking instruments was a winning one for the organizers of staged entertainments that evoked England’s past and the age of Shakespeare. Nellie was quick to make the most of this opportunity. As early as 1905, at the Guildhall School of Music, she presided at the harpsichord in a re-enactment, with voices, strings and oboe, of Thomas Campion’s Maske of the Golden Tree, first performed in 1614 with songs by Campion, Nicolas Lanier, and Coperario. For the revival, the instrumental music was seventeenth-century, but some vocal music “imitating the style of the period” was written.

Campion also featured in an Elizabethan festival at Hatfield House in 1924, a fundraiser organized by the then Lady Salisbury for the Herts. County Nursing Association. It featured an “Elizabethan marketplace”, a procession of local worthies from the new Hatfield House to the Old Palace, the childhood home of Elizabeth I, and a revival of Campion’s masque Zephyrus and Flora (1607) – its first performance for 300 years. Nellie and Dorothy Chaplin (her niece) arranged the dances, which were all taken from Nellie’s “Ancient Dances and Music”. According to one review, “the dancing of the Corranto by one of the ladies of the court was one of the highlights of the whole performance.”

Nellie and her company were in demand at events such as the “May Day Revels” at the Globe Theatre (1913), with historical dances arranged by Nellie; a masque depicting scenes from the lives of Anne Boleyn and Elizabeth I, followed by a re-enactment of the signing of Magna Carta, held at Great Fosters near Runnymede, in June 1926; and performances, including some sixteenth-century dances arranged by Kate, at an Elizabethan-themed exhibition, called “Shakespeare’s England” at Earl’s Court, May–October 1912, where a reconstructed Tudor townscape with winding streets, little shops, and replicas of famous buildings of the period was designed by the great architect of Victorian imperialism, Sir Edwin Lutyens.

A re-enactment of Merrie England?

Nellie also arranged and performed music for plays by Shakespeare and his contemporaries, for instance the plays performed at the Earl’s Court exhibition and a production of The Taming of the Shrew at London’s Prince of Wales Theatre, in May 1913.

Inevitably, given the very English flavour of these events, the focus of Nellie’s work on dance shifted from France to England. Although she had begun her researches into early dance with French manuals of courtly dance, and announced sweepingly that “dancing as an art is French”, she describes the English country dances she found in John Playford’s Dancing Master (first published in 1651 and frequently reprinted) as possibly more important than the French courtly dances.

This intense interest in English music and dance of the past reflects a yearning, both nostalgic and idealistic, for an imagined Golden Age in England when “villagers mixed with the gentry in all festivals”. The 1912 exhibition is a classic example: as well as the performances by Nellie and her company and the Shakespeare plays for which they provided the incidental music, there were daily performances by Mary Neal’s Morris dancers at the replica Fortune theatre, the performers dancing their way through the “crowded narrow streets” to the theatre.

“The whole [event]”, one reviewer wrote at the time, a little patronizingly, “conjured up pleasing visions of our forebears, and made one reflect that in their own way they were really very well off for music in those days.”

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Jeremy Barlow, who first mentioned the Chaplin sisters to Semibrevity; Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation; Professor Freia Hoffmann of the Sophie Drinker Institut in Bremen, who kindly shared her very extensive research; Sandy Mitchell; and Michael Mullen and Elizabeth Wells of the Royal College of Music.

© Mandy Macdonald 2016 – All rights reserved

Leave a Reply