|

|

![FLTR: Harry Danks (treble viol) Stanley Wootton (treble viol) Jacqueline Townshend (tenor viol) Desmond Dupré (tenor viol) ]](//www.semibrevity.com/wp-content/uploads/london-consort-of-viols-z1-1024x661.jpg)

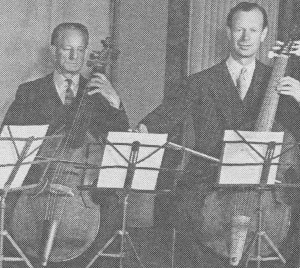

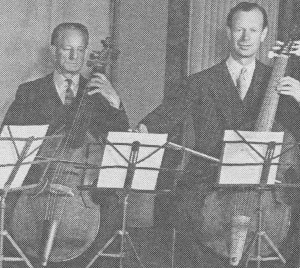

FLTR: Harry Danks (treble viol), Stanley Wootton (treble viol), Jacqueline Townshend (tenor viol), Desmond Dupré (tenor viol)

The musicologist and Dolmetsch student, Robert Donington (who himself was a member of the group, 1950–1961), once referred to the London Consort of Viols (LCV) as a “semi-official BBC team”, and they certainly might well have been called the BBC Consort of Viols, as their primary focus was performing for the then Third Programme, now BBC Radio 3.

Their leader, Harry Danks (1912–2001), left school at the age of 14 to work in a factory and, shortly after, graduated to playing the violin in a cinema ensemble, having been taught by two of his uncles. His musical life is nicely summed up in this extract from Tully Potter’s obituary:

Of all the pupils of the great viola virtuoso Lionel Tertis, Harry Danks, who has died aged 88, enjoyed the most multi-faceted career – as orchestral principal, viola soloist, chamber musician, leader of a viol consort and authority on the viola d’amore.

Below, Harry Danks describes the early days of the Consort:

One day in 1948, Sir Steuart Wilson [BBC Head of Music] asked me to meet him in his office and invited me to consider forming an ensemble of viols. No promises were made, but it was implied that if the ensemble became successful the BBC Third Programme would be interested.

I discussed this with three of my colleagues in the [BBC Symphony] Orchestra: Jacqueline Townshend, who at that time shared the first desk of violas with me; Stanley Wooten, the number three player in the same section; and cellist Henry Revell. […]

We rehearsed most days, always finding a free half hour while at the Maida Vale studios during our normal working life in the Symphony Orchestra.

We soon began to make a decent sound under Elizabeth Goble’s instruction, and felt the time had come to devise a programme of music that could be offered to the BBC. We chose the music of Byrd, [Simon] Ives and Jenkins in a programme intended as an audition trial.

In fact, it was accepted for transmission and went out on the Third Programme on 19th May 1949 with a repeat on 5th September 1949.

We were very soon invited to play consort music for five and six parts.

Elizabeth Goble, wife of the harpsichord maker Robert Goble, had been a harpsichord and gamba student of Arnold Dolmetsch, and was an influential teacher who played in the English Consort of Viols, established in the 1930s by Marco Pallis and Richard Nicholson.

Veteran music journalist and writer Tully Potter suggested that Wilson “wanted to broadcast the riches of the English viol consort repertoire without bringing August Wenzinger’s group from Basel every time”, and certainly their BBC radio appearances were considerably reduced shortly after the LCV was formed.

Danks:

One of our first engagements outside the BBC was from the Arts Council. We were invited to join the Westminster Abbey Choir in the Abbey to record “This is the record of John” [by Orlando Gibbons] for the Columbia Record Company under the direction of Sir William McKie.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

The instruments

FLTR: Henry Revell and Robert Donington (bass viols) Until December 1949, according to documents held at the BBC Archives, the LCV played on borrowed instruments, which had been organized for them by Alec Hodsdon, the harpsichord maker. We don’t know which instruments these were or from whom they were borrowed.

The BBC supported an application to import a “matched set” of viols from the then American Zone of Germany (probably from Eugen Sprenger Sr. in Frankfurt), but the Board of Trade refused permission and advised them to obtain the viols from Messrs. Arnold Dolmetsch Ltd of Haslemere, Surrey.

There were some discussions about whether the BBC should buy them, but it seems that they were bought from Dolmetsch by the individual musicians concerned. It’s not clear whether these viols were actually made by them (in which case, Dietrich Kessler could have been involved), or if they came from their stock of second-hand and antique instruments. As a pay-back for the players’ personal investment they were contracted for 24 broadcasts in 1950 – almost one every two weeks.

According to Ysobel Danks (who herself played occasionally in the Consort from 1958), her father’s treble was old. Thomas MacCracken has suggested that this instrument, with its flame-shaped sound-holes and carved head, may have originally been a viola d’amore, which perhaps had been cut down for conversion to a viola, then re-necked to be used again as a viol, but without building the ribs back up to their original depth.

The unusual white pegs on Robert Donington’s bass, seen in the photo above, suggest (to MacCracken) an instrument attributed to Martin Hoffmann of Leipzig, that once belonged to him. Desmond Dupré obviously brought his own (modern) tenor, perhaps made by Maurice Vincent, when he joined the group.

Broadcasts

The heyday of the LCV was in the 1950s, and by July 1956 they had already made more than 100 broadcasts. Thereafter, they performed only once or twice a year on radio, as the original members retired or moved away.

Their repertoire consisted overwhelmingly of English music, and the programmes often included choral music, in which the viols were only rarely involved, or keyboard pieces, played on the organ or harpsichord by the likes of Thurston Dart, George Malcolm, Lady Susi Jeans and Ralph Downes.

By the time a ‘Studio Portrait’ of Harry Danks was broadcast in February 1965, the Consort was already long in decline. Consequently, for this programme, Danks’s daughter Ysobel was drafted in and Ambrose Gauntlett – who had never played with them before – took the bass part. Their final radio performance was of a programme of ‘Early Scottish Songs’ on 24 May 1966, contracted for the Scottish Home Service.

Concerts

According to Ian Gammie, in his 2012 article on the LCV in The Viol, many of their concerts were given at music clubs, which explains why so few are mentioned in newspaper archives. Here are some of their documented highlights:

In the summer of 1951 the London Consort of Viols gave three concerts in the Wigmore Hall series “Music by English composers, 1300–1750”. According to The Times, they demonstrated a “suppleness of phrasing rarely achieved with viol bowing”, in contrast to previous “jerky” attempts.

They also played at the memorial concert for E.H. Fellowes in the Livery Hall of the Goldsmiths’ Company, on 28 April 1953, using music edited by him. The other performers were the BBC Singers, directed by Leslie Woodgate; the highly successful one-to-a-part madrigal group, the Golden Age Singers (est. 1951), directed by Margaret Field-Hyde; Peter Pears and Julian Bream, songs with lute; and Thurston Dart, harpsichord.

In May 1953 they performed at the Bath Festival.

In October 1954, Denis Stevens, writing in the Musical Times, wondered “whether there ever was such a thing as an a cappella choir; certainly the London Consort of Viols, in the Gibbons programme from King’s College, Cambridge, made these fine verse anthems sound more convincing than I have ever known.”

They played at the Commemorative Festival to mark the tercentenary of the death of Thomas Tomkins, held at St. David’s Cathedral, Pembrokeshire, South Wales from 13 to 17 August, 1956. Some of the proceedings were relayed by the Welsh Home Service, and a 55-page Souvenir Brochure was also issued. Apart from the Consort, with “the full ensemble of six [which] collaborated in fine style”, Alfred Deller (counter-tenor), Desmond Dupre (lute), Thurston Dart (harpsichord), and the Deller Consort were involved, along with organist Harry Gabb and the cathedral choir, under their director, Peter Boorman.

The London Consort of Viols were important pioneers who bowed underhand on unaltered viols with frets – a practice which was far from universal in their day. They certainly fitted in well with the ethos of new BBC Third Programme, which was promoting the introduction of previously unknown repertoire on original instruments. Their work, though, was only ever a sideline for the four core members, whose “day job” was with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, and they did not teach or establish a tradition, as was the case with Wenzinger’s group in Basel. Perhaps if they had made more than that single commercial recording, accompanying the Westminster Abbey Choir in Gibbons, their name might still be known today.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Ian Gammie, Ysobel Latham (née Danks); Thomas MacCracken; Kate O’Brien (BBC Archives researcher) and Tully Potter.

The Belgian early music pioneer explains why period style matters, no matter what period.

by Clive Paget

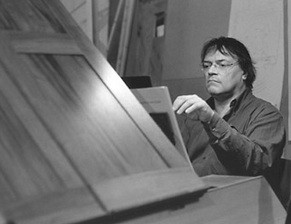

“For me Stockhausen and Messiaen is early music.” Now there’s a provocative statement, but then Jos van Immerseel has been provoking a response on and off for 40 years now. The Belgian early music pioneer [ … ] is talking to me over the phone from Mexico City where he’s appearing with his period band Anima Eterna, a truly globe-trotting phenomenon.

These days he’s as likely to be found applying his mind to ‘authentic’ Ravel and Janáček as he is to be playing Mozart on his beloved fortepiano, but this questing musical personality has never forgotten his roots, nor the catalysts that launched him on a collision course with the music of the late baroque and the classical era.

“I didn’t start with early music, that came later,” Van Immerseel admits. Starting out as a piano and the organ student in the 1960s (the maestro turned 70 last year), up until the age of 18 he played what was considered normal repertoire before heading to Antwerp for further studies. But then it all changed. “I was a little bit shocked in the conservatory,” he explains. “In the piano class we ignored the style and specific character of the repertoire. We played Bach exactly the same way we played Rachmaninov. “I didn’t start with early music, that came later,” Van Immerseel admits. Starting out as a piano and the organ student in the 1960s (the maestro turned 70 last year), up until the age of 18 he played what was considered normal repertoire before heading to Antwerp for further studies. But then it all changed. “I was a little bit shocked in the conservatory,” he explains. “In the piano class we ignored the style and specific character of the repertoire. We played Bach exactly the same way we played Rachmaninov.

But in the organ class we had really incredible lessons on the different styles of organ and the different styles of the music. That was fascinating for me and was really important when it came to making my choice.”

Study with the great harpsichordist and musicologist Kenneth Gilbert initially saw Van Immerseel winning accolades as a keyboard specialist. “I tried to find very historical harpsichords and to study this instrument to see the possibilities and the limits”, he tells me, but soon his ambitions led him further into the field of original instrument practice and orchestral music of the 18th century.

“I developed my own work and methods but I was also in contact with pioneers like Gustav Leonhardt and Harnoncourt and with colleagues like René Jacobs and Paul van Nevel,” he admits. “I wasn’t isolated but I was not in a so-called movement or school. I was doing my own things.”

In 1987 Van Immerseel founded his own orchestra, Anima Eterna. “We started with Mozart, playing all the piano concertos and recording them,” he explains. “At the end of the cycle the orchestra grew up to a small symphony orchestra and so we started to play symphonies by Mozart and Haydn and so we arrived automatically at Beethoven.”

For a dedicated ten year period, Anima Eterna committed itself to exploring the complete Beethoven cycle, touring them across Europe and famously recording them back in 2008 on the boutique Zigzag label. [ … ]

Beethoven changed so much about the way we think about the symphony today – not just the structure and purpose of the music, but the size and makeup of the orchestra as well. Over a period of 25 years he transformed music in his time and that should all be evident as the Anima Eterna orchestra expands in terms of number of players across the cycle [ … ].

For Van Immerseel, it’s more than just a question of authentic instruments. “That’s a part of the job,” he says “Good instruments can show you the limits and the possibilities of the music, but there is also the study of the phrasing, of the tuning, of the style, of the tempi. Then there’s the composition of the orchestra, the art to setting out the instruments, the technique to play them etc. All these things are important.” And that all changes across the cycle. “Violins use older bows in the early symphonies and more advanced bows in the later symphonies. And they play with all different kinds of gut strings.”

Early on, Van Immerseel took the idea of playing in historically informed style on instruments of the period and applied it to Berlioz, Schubert and so on up to Brahms.

In recent years he’s gone even further recording Orff’s Carmina Burana as well as Dvořák, Poulenc and Ravel. “We played Ravel on French instruments and the sound is completely different compared with what you hear normally,” he enthuses. “ It’s much more transparent and there are more colours. Playing this music on the right instruments you understand the music better. You see why a composer writes such a timbre, such a motif, such notes, such a compass and that’s really difficult to find out if you play all the music from the past on the same instruments – that’s not logical!

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

Listening to his often-pugnacious analyses, there’s definitely a touch of the evangelist about Jos van Immerseel. His philosophy is all embracing and distinctly catchy. “I like to compare a piece of music with food or with a kitchen,” he proselytises. “If you are an admirer of the Japanese kitchen, then you try to find a restaurant with Japanese food and with Japanese ingredients and not, for example, Italian ingredients. If you like an Italian kitchen then you do the opposite. In art it’s absolutely normal that if you have a picture by Van Gogh or by Caravaggio restored, then the restoring method is completely different. It’s the same in architecture and literature and so on. Only in the music do we play all the music on the same instruments. It’s stupid – sorry – but it’s stupid!

Next year Anima Eterna plays Enescu and De Falla, and in two years time a Gershwin program. “For me, good music is for all time,” Van Immerseel explains. “We try to adapt to every composition with the right instruments. My clarinet player for example plays on 16 different clarinets. That’s normal if you do this seriously.”

And as he boldly goes, does he see an end point? Will we be hearing period Messiean and Stockhausen in the future? “We do Messiaen next year,” he declares. “Stockhausen, I don’t have a special feeling with this music, personally. So for the moment no Stockhausen …” Shame.

Copyright © 2016 Clive Paget – All Rights Reserved

This article was originally posted by Limelight Magazine, Australia. This edited version is reprinted here by permission.

Presentation of the Erasmus Prize, 8 September 1980. F.l.t.r.: Alice Harnoncourt, Marie Leonhardt, Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Gustav Leonhardt. © Marcel Antonisse/ Anefo; Nationaal Archief, archiefinventaris 2.24.01.05, inventarisnummer 931-0044 Speaking in an interview in 2012, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who died on 5 March 2016, aged 86, said that his closest musical friend was Gustav Leonhardt.

Their best-known cooperation is undoubtedly their complete Bach church cantatas, recorded between 1971 and 1989, for which they were jointly awarded the Dutch Erasmus Prize in 1980. Leonhardt gave his share of the prize money to the Oudezijds 100 Society, a centre for prostitutes and drug addicts in the Red Light district of Amsterdam; while Harnoncourt subsidized the Complete Mozart Edition with his share.

Early days

Harnoncourt and Leonhardt first met in 1950, in a corridor of the Vienna Music Academy, where Harnoncourt was studying cello with Emanuel Brabec. At the time Leonhardt was known simply as a Dutchman who spoke good German; which was not surprising, as his mother was Austrian, had been brought up in Graz and, oddly, knew Harnoncourt’s mother because they had both attended the same school!

Their first conversation was less than auspicious: they argued about Die Kunst der Fuge, which Leonhardt insisted could only be properly played on the harpsichord. Harnoncourt obviously didn’t agree, for at that stage he had already spent more than a year learning that piece with his Vienna Gamba Quartet (established in 1949 with Eduard Melkus, Harnoncourt’s future wife Alice Hoffelner, and Alfred Altenburger). This difference of opinion was, however, not an obstacle to their becoming close friends.

According to Marie Leonhardt, during those early days Harnoncourt and Leonhardt spent time together almost every day, playing and arguing about music late into the night. Harnoncourt reported that “we played many, many concerts together”, until Leonhardt moved permanently to Amsterdam in 1955. Presumably these concerts were in churches and smaller locations in Vienna, as there’s no record of Harnoncourt and Leonhardt ever having played together at the Musikverein, where Leonhardt made his solo debut (with Die Kunst der Fuge, on the harpsichord) in the Brahms-Saal on 7 April 1951.

But why was Leonhardt in Vienna, anyway?

Following his graduation from the Schola Cantorum in Basel, Leonhardt had come to Vienna – originally for one year only – to study conducting. This would give him a fallback occupation and placate his businessman father, who thought it unlikely that there was a living to be made by playing the harpsichord. In fact, Leonhardt attended very few conducting classes, and spent his time researching old editions and manuscripts in libraries.

Momentous times

The year 1953 was important for both musicians. Harnoncourt was to establish his Concentus Musicus (the first period-instrument orchestra in Europe), with his wife, his brother-in-law, Kurt Theiner, Eduard Melkus, and younger colleagues from the Vienna Symphony Orchestra; Leonhardt was to embark on the first version (see here) of the Leonhardt Consort, with his wife, a cellist, and the recorder player Kees Otten.

Both groups rehearsed in the living rooms of their respective founders, and both required a significant gestation period, before they were ready to be exposed to the general public. For the second version of the Consort (see here), this was almost two years; and for Concentus Musicus four years, not counting their anonymous participation in a production of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo conducted by Paul Hindemith. Their official debut concert was at the reopening of the Schwarzenberg Palace in Vienna in May 1957.

Not surprisingly, it was Leonhardt who recommended that Martin Skowroneck make them a lightly-braced Italian harpsichord – his first truly historical instrument – to balance with their authentic strings (see this blog).

“For [authentic] musical instruments, we were willing to do almost anything,” Harnoncourt wrote of his life in the 1950s, when money was scarce, and this involved becoming a rank-and-file cellist in Herbert von Karajan’s Vienna Symphony Orchestra in 1952, a job which he endured till 1969.

According to his obituary in the Guardian,

he reacted strongly against both the military precision of conductors such as George Szell and the undifferentiated approach to early music then prevalent. Handel was played much like Brahms, he later said, and the result was “an unsorted blend of geniality, 19th-century tradition and ignorance”.

Early recordings

Harnoncourt and Leonhardt played, with members of the Vienna Chamber Orchestra, in the 1950 Supraphon 78 rpm recording of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos 3, 4 and 6, conducted by the unsung early music pioneer and teacher, Josef Mertin (1904 – 1998), whose interpretation classes they had both attended. Leonhardt was involved here only as a gamba player, in No. 6, with someone else playing the harpsichord.

They also played together in the Leonhardt-Barockensemble (with other family members), in three recordings made for the American label Vanguard in May 1954, with Alfred Deller (see this blog).

In the early 1960s, the two men were brought together again by Telefunken’s Wolf Erichson, who was to produce countless recordings in which they took part, including the feted Bach cantata series.

Here’s Alice Harnoncourt speaking about her Stainer violin, playing gambas and the early days of Concentus Musicus in a 2001 radio interview (in German).

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

Harnoncourt and Leonhardt compared

A major difference between their early careers is that Harnoncourt remained a full-time orchestral cellist, while continuing to develop Concentus Musicus, and Leonhardt’s took off very quickly, primarily as an early music “expert”, harpsichordist and organist; for him the Consort was only ever a sideline. An indication of his success is that by 1960, he had bought a genuine unaltered Ruckers harpsichord (a very expensive rarity, even then) and was already doing his eighth annual solo tour of the USA!

Leonhardt was fascinated by Harnoncourt’s extensive collection of authentic instruments (more than enough to equip a small orchestra), which he’d found in antique shops, monasteries, attics and auction houses, and bought at low prices because no one else wanted them. In Holland, Leonhardt had only seen his cello teacher’s newly-made gamba and violoncello piccolo, which were really just modern cellos with different stringing.

Strangely, although Harnoncourt started the gamba before 1949, it was not until his involvement, with Leonhardt, in Straube’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach, in 1967, that Harnoncourt started to play it with under-handed bowing (see below). Everything in the film was authentic, down to the last detail; so he could hardly play the gamba, in the role of the Prince von Anhalt-Cöthen, commissioner and dedicatee of Bach’s gamba sonatas, looking like a 20th-century cellist.

Divergent paths

Leonhardt repeatedly said that there was enough early music to fill several lifetimes, let alone one; he never played music from later than the end of the 18th century, and only once made a recording on the fortepiano. He conducted comparatively rarely, and in 1998 said, “Why wave your arms around when your fingers still work?” He gave around 100 concerts each year, mostly solo harpsichord recitals, right up until the end of his life.

For Harnoncourt, in contrast, from 1972, when he made his debut on the conductor’s rostrum with Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria at the Piccola Scala in Milan, his focus was on leading from the front rather than from the cellist’s desk. His work with Concentus Musicus continued, though, and apart from their many recordings they gave some 250 concerts between 1968 and 2015 in the Musikverein in Vienna alone.

As his repertoire broadened to include Bruckner, Schumann, Beethoven, Brahms, Alban Berg, Offenbach and Dvořák, among others, he was invited to conduct “modern” orchestras, such as the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, the Concertgebouw Orchestra and, later, the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonics, even making two appearances at their New Year’s Day concerts, in 2001 and 2003. Aged 80, he continued to surprise and delight by recording Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, typically making his own “authentic” version, based on original sources.

Harnoncourt’s recent obituaries recognized this:

according to The Times, “Nikolaus Harnoncourt was unquestionably the foremost authority on historically informed performance”; the Telegraph led with “Brilliant conductor who relentlessly pursued authenticity in both early and modern music”; in Scotland the Herald said, “A rival and, some would say, the obverse of the ostentatious, autocratic Herbert von Karajan, to whose conducting style he was in every way opposed”; he’s described in the Guardian and elsewhere as “one of the most influential conductors of the 20th century”.

Legacy

Leonhardt didn’t like talking about himself: he often said, “I’m just a performer”, and was averse to having live performances recorded or filmed. Most of what we have of him consists of around 200 studio recordings, plus a film of him conducting a Bach cantata and, somewhere in the archives, a few clips and an interview from the 1970s filmed at his house on Amsterdam’s Herengracht, for Dutch TV. There’s also an hour-long TV programme, online, with Han Reiziger, in Dutch, with subtitles.

Leonhardt wrote only one book on music (in 1952, about Die Kunst der Fuge), but did contribute some articles and a preface to a few works; here’s a comprehensive list of his publications.

There’s also a biography in French, Jacques Drillon’s Sur Leonhardt, based mostly on previous interviews. A short amateur film of him improvising – in 17th- and 18-century styles – on an old organ in St. Petersburg has recently surfaced on Facebook.

In contrast to Leonhardt, Harnoncourt wrote several books about his approach to music (some of which have been translated), and there are also a number written about him. The following are available only in German: a 50th anniversary volume about Concentus Musicus (Die seltsamsten Wiener der Welt); a 1999 biography by Monika Mertl, and Being Nikolaus Harnoncourt, published to celebrate his 80th birthday. As he didn’t object to being recorded or filmed, there are many commercial DVDs and YouTube videos of him conducting, giving master classes, taking part in documentaries, being interviewed (a particularly nice one, on his 85th birthday, is here).

He also made an amusing appearance on a popular Austrian TV talk show, see here,

in which gives as good as he gets from the two rather irreverent hosts.

Another particularly charming short film is with Cecilia Bartoli, in which they talk about and perform excerpts from Haydn’s Armida.

Harnoncourt made more than 500 recordings. There’s also a fascinating and comprehensive website, with family photos and a timeline, which charts his life and career from the very beginning.

Although Harnoncourt’s full name was Johann Nikolaus Graf [Count] de la Fontaine und d’Harnoncourt-Unverzagt, and he was related to Hapsburg emperors and half the royalty of Europe, it was Leonhardt who had the aristocratic bearing. According to a former Harnoncourt student, the only indication of his noble roots was that he had very good manners.

Copyright © 2016 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

Guest blogger: Edward Breen PhD

(London-based musicologist, writer and lecturer; see here for more of his work.)

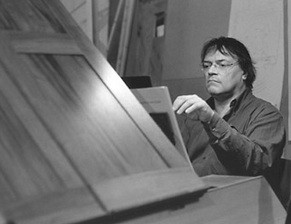

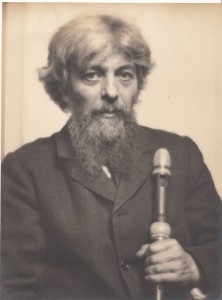

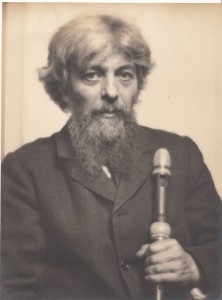

Michael Morrow (1929-94) was the director of Musica Reservata, an early music ensemble active in the 1960s and 70s with a repertoire that spanned from medieval to baroque. (Their discography can be seen here.)

Although Morrow was the director and often the editor of the editions used by the ensemble, harpsichordist John Beckett conducted performances. The ensemble included many superb musicians such as the organologist and percussionist Jeremy Montagu; recorder player John Sothcott; singers Ian Partridge, Nigel Rogers, Grayston Burgess, Paul Elliot and Jantina Noorman; and other instrumentalists David Fallows and Christopher Page, David Munrow, Anthony Rooley and Andrew Parrott. Parrott, incidentally, also conducted the ensemble in the early 70s after Beckett’s departure. Musica Reservata was not of course the only early music outfit to boast such specialist personnel at that time, but it does appear to have been quite an important meeting place for those musicians who specialised in medieval repertoire.

In Britain, in particular, the BBC was at the heart of key early music advances. Morrow, born in Ireland and bedridden for much of his childhood with an aggressive form of haemophilia called Christmas disease, openly acknowledged the role the BBC had to play in his own musical education and in the development of Musica Reservata. In one script (perhaps for a pre-concert talk) he paid specific tribute to the Third Programme:

Shortly after World War II the BBC Third Programme was established with the aim of bringing to the general public music, poetry and drama that was either too old, too new or too exotic to form a part of the accepted repertory. Previously, the only regular opportunity for the average listener to hear preclassical music was in the form of gramophone records. These, however, were limited in scope, owing to the lack of public interest, and to the severe restrictions imposed by the limited playing time of the 78 records. The only early music recorded was, virtually, the incomparable Nadia Boulanger Monteverdi records, made in 1937, and odd snippets of this and, occasionally, of that, in the French collection Anthologie Sonore and the English Columbia History of Music – both series musicologically out of date practically before they were conceived.

This, then, was the state of affairs before the BBC Third Programme began its marathon series of series, that included a year-long history of music, a geographical and historical survey of plainsong, a history of English lute music (performed by the foremost lutenists in England and Europe), numerous programmes of non-European music, and of folk music from most countries. Without this musical background neither Musica Reservata nor, indeed, any other English professional early music ensemble could have come into being.

(Michael Morrow, “Musica Reservata,” February, 1971, King’s College London Archives.)

Morrow highlights an important part of the Third Programme’s legacy, its wide selection of early music, world music and folk music. [See also the blog post on Desmond Dupré, who was a regular member of Musica Reservata.]

Morrow studied fine art in Dublin before settling in London in the mid 50s where he took a job operating the musical fountains at a Moroccan restaurant in Piccadilly Circus. He sat inside a control booth pulling levers to make the fountains squirt water in time to music.

In London he reconnected with his friend and fellow Irishman, the harpsichordist John Beckett who was by then performing as a duo with the recorder player John Sothcott who had studied at Morley College with Walter Bergman. Sothcott remembers at their first meeting, Morrow had only a lute that had begun life as a theatre prop but which had been adapted for playing. The result of their musical experiments was an invitation to perform for ‘The Society of The White Boar’ renamed ‘The Richard III Society’ in 1959. They performed the early music that they had been exploring with several friends (including Jeremy Montagu who at first played jazz tom-toms as a stand-in for nakers). It was from this concert that Morrow, Beckett and Sothcott founded Musica Reservata and went on to give an inaugural concert in Fenton House, Hampstead in 1960.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

Musica Reservata may have been founded by three friends but appears to have been driven chiefly by Morrow who became more fanatical about issues of performance practice as time went by. There are two interesting connections that Morrow made which seem to have had a deep influence on his approach to early music, medieval in particular, and these both relate back to themes explored in the Third Programme broadcasts mentioned above. The first came through Eric Halfpenny, a founder member of The Galpin Society, performer (on cross flute) in that first Musica Reservata concert, and author of a 1943 paper ‘The Influence of Timbre and Technique on Musical Aesthetic’ (The Music Review, iv 1943, p 250). Halfpenny wrote convincingly about the need to hear music played on the instruments for which it was originally conceived and indeed, it was the very sounds of early instruments that were to play such an important role in defining performance practice for Music Reservata throughout the 1960s and beyond.

Another key influence was the folklorist A.L. Lloyd (Bert Lloyd). Morrow certainly knew of Lloyd’s work through his recordings, especially of Bulgarian Music, for Columbia records. Lloyd helped Morrow realize close connections between medieval music and longstanding traditions in folk music communities.

To pursue this line of reasoning for a moment, there is a picture that accompanied Morrow’s 1978 article ‘Musical Performance and Authenticity’ (in Early Music vol. 6, no. 2) showing a group of bagpipers dancing to gudulka accompaniment (a Bulgarian folk instrument closely related to the medieval rebec) and that photograph was taken by Lloyd himself. It can be compared to another shot from the same event featured on his Columbia album booklet (page 6).

It was a folk LP that stopped Michael Morrow in his tracks one day. John Sothcott remembered the incident when talking to Christopher Page on Radio 3’s Spirit of the Age series in the early 1990s:

I remember with the Kalenda Maya piece at the beginning for example – we were working out ways of doing that and we went into the record shop in Hampstead and heard a Romanian pipe player playing some very percussive dance music with a drum and we suddenly realized this was the sort of approach that would suit that Kalenda Maya – or would be one approach that would suit it and didn’t seem to clash with any of what we knew about the performance of this area of music. And I remember that grew that evening from that performance of music and almost exactly as we did on the record it never altered. By I think that time we had Jantina Noorman of course with us who makes a very special sound.

Speaking also in that interview Jeremy Montagu remembered that Morrow had taken Noorman to meet Lloyd so he could advise her on singing styles. Lloyd was indeed a catalyst for Jantina’s constructed style.

Listening to Kalenda Maya from its first Musica Reservata recording one can clearly hear the influence of Balkan folk techniques on Jantina Noorman’s singing.

This, however, was not the way Noorman had always sounded, it was a constructed style arrived at through trial and error. The difference is clearly heard in this recording of Dutch folk songs from the 1950s before she began her long association with Musica Reservata. [See this 2005 article about her, with extracts from an interview.]

Another key influence for Michael Morrow in the 1950s came when he heard the Bulgarian State Company perform at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall. And indeed, Michael Morrow himself mentioned the importance of Balkan voices in unlocking the sound of Medieval Music many times throughout his life. In 1967 he played extracts from two of Lloyd’s Bulgarian recordings on BBC radio to illustrate points about singing. Bulgarian singers, he felt, exemplified the ‘modified shout’ that was produced by singers during the Middle Ages and renaissance as opposed to the ‘modified speech’ that later singers cultivated.

Furthermore, Morrow was keen to avoid performances in equal temperament because the harmonic idiom of medieval music – particularly drones –demanded a precise intonation. The standards of Bulgarian singers were again drafted in to justify his point.

To illustrate how Morrow appears to have been influenced by some of the sounds he heard recorded by Lloyd, listen to the strident way the Gudulka is played in Lloyd’s Columbia Records recording of Pushka pukna (if you can get hold of a second-hand recording), then listen to the rebec playing on the opening of this dance from Musica Reservata: La Quarte Estampie Royale (if you can’t find the Columbia album then try listening to Otreyala Mesechina from Folk Music of Bulgaria for a similar but less-pronounced effect).

These days that feels like a small point, but it is extremely significant that the straightforwardness of the playing was startlingly new in early music in the 60s. Not even the New York Pro Musica ever used quite that sort of ‘bite and attack’.

In fact, ‘bite and attack’ is the very term used in Musica Reservata biographies to explain how their sound was dictated by instrumental construction. Techniques of bowing and blowing were chosen to ensure rock-solid intonation, and this in turn was felt to set a certain benchmark for style and texture.

With such realisations about instrumental playing, Morrow then figured that voices, being naturally more flexible, would have been obliged to blend their sound so that it was not incongruent with the instrumental texture. He wasn’t asking singers to imitate the instruments as much as simply to behave like them. And the catalyst for this vocal style was Balkan voices. Here’s how he put it in a pre-concert talk:

[…] vocal tone has always been related to the tone produced by the instruments of the time, and it seems unreasonable to expect musicians of any period to admit serious incongruity between vocal and instrumental colour […]

So the outline of the Musica Reservata project seems to have been based on instrumental playing. First, the instruments had to be played in such a way as to maintain the most accurate intonation possible, which often meant blowing, or bowing stridently. Then the singers were asked to articulate their musical lines similar to the instruments, and to use a ‘modified shout’ to balance the ensemble. Through Bert Lloyd, Morrow found useful models in Balkan singing that closely matched the qualities he sought. And in Jantina Noorman he found a singer who not only could, but also would, try such singing techniques in early music.

© Edward Breen 2016 – All rights reserved

Edward Breen’s essay “Travel in Space, travel in Time: Michael Morrow’s Approach to Performing Medieval Music in the 1960s” will be published in July 2016: Studies in Medievalism XXV: Medievalism and Modernity.

A Kirkman harpsichord from 1755, similar to that used by Nellie Chaplin. By courtesy of Musical Instrument Museums, Edinburgh (MIMEd 4330). By Guest Blogger: Mandy Macdonald

The fascination of old instruments

The use of historical instruments contributed greatly to the charm of the concerts given by the Chaplin sisters and drew in audiences. Both Nellie and Kate owned eighteenth-century instruments. Nellie’s first instrument was a Jacobus and Abraham Kirkman of 1775, which she had on loan from Nellie Woodward-Taphouse, step-daughter of the Oxford musical instrument dealer and collector T.W. Taphouse; in 1908 she bought another Kirkman (this time, by Abraham and Josephus), with two manuals, 2 x 8’, 1 x 4’, buff and machine stops, dated 1789 – though she blithely modified it in a way we might think irresponsible today, by having the Venetian swell removed.

[In 1916 Nellie “came across” another Kirkman harpsichord originally made in 1766 for Princess Amelia, the youngest daughter of George III, which had been given as a 16th-birthday present in 1874 to Ellen Willmott, the famous amateur botanist. This instrument, which was always called the “Princess”, was lent to Nellie, who paid for its refurbishment. According to the correspondence between them, it was helpful for her to have two instruments due to her many engagements.]

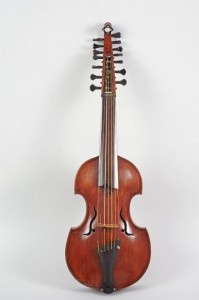

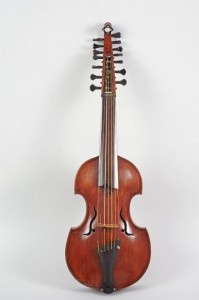

A viola d’amore made by George Saint-George in 1912, similar to one used by Kate Chaplin. By courtesy of Musical Instrument Museums, Edinburgh (MIMEd 4080). Around 1906, at the suggestion of Nellie’s friend, the London-domiciled Belgian cellist, musicologist, and writer, Edmund van der Straeten (1855–1934), Nellie’s younger sisters began to learn instruments more in keeping with the timbre and volume of the harpsichord. Kate was taught the viola d’amore by George Saint-George (1841–1924) a virtuoso player, composer, and skilled luthier, who built an instrument for her. In 1925 we find her playing Saint-George’s arrangement for the viola d’amore of “The Irish Ho-Hoane”, from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.

Mabel, the cellist, was to start the bass viol, taking lessons from Van der Straeten, who himself was an important viol pioneer, and he tells us that she became “in a very short time an excellent player on that difficult instrument”. Mabel owned a highly decorated six-string viola da gamba (see here and below) made in 1718 by Barak Norman (c.1670 – c.1740), which is now in the possession of the Smithsonian Institution.

Mabel’s 1718 Barak Norman viola da gamba, by kind permission of the Smithsonian Institution The instruments themselves became a talking point for audiences and reviewers of the Chaplin Trio’s performances. In November 1912, for example, a much-reported concert of music from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, given at London’s Aeolian Hall in aid of the Shakespeare Memorial Fund, included Bach’s D minor triple concerto – possibly its first modern British performance – played on three harpsichords dated 1775, 1782 and 1789 (the latter presumably the one belonging to Nellie). “The effect of this old-world music on the three old-world instruments was enchanting”, the reviewer rhapsodized.

His comment is fairly typical of reviewers’ reactions to the Chaplin “product”, which was regularly described as “quaint”, “charming”, even “fragrant”; but the reviewers also often thought the sound of the Baroque instruments “thin” and weak – which it probably was, given the size of the concert halls that they were expected to fill and the fact that they seem often to have been used in conjunction with modern instruments.

A reviewer of one of the very first revival concerts (December 1904) wrote almost apologetically:

… the quaint old instruments of the time, the clavichord, spinet and harpsichord, … in spite of their thin and, to modern ears, possibly unfamiliar sound, still remain the proper instruments for the true interpretation and the delicate charm of the music of the period.

The problem persisted throughout their careers: as late as October 1927, a Times reviewer noted, even while applauding the performance’s approach to historical accuracy:

a slight difficulty arises from the faint tone of the harpsichords used by Miss Chaplin, which are Kirkmans of the eighteenth century … there is no gainsaying the fact that owing to the difficulty of clear hearing among the players the ensemble was faulty.

Detail of Mabel’s gamba Nonetheless, by 1913 the trio’s “Ancient Dances and Music” shows were being described as “fashionable”, and they became something of a “brand”: the combination of dance and music and the novelty of the historical instruments made them highly popular with audiences, and the trio, led by Nellie, repeated the format again and again from 1905 right into the 1920s, around the country and on radio.

“Modern troubadours” at the battle front

During the first world war the trio were among 600 performing artists who formed “concert parties” to give entertainments to the troops in France. This support to the war effort was organized, somewhat surprisingly, by the Women’s Auxiliary Committee of the YMCA in London, and concert parties were sent out more or less continuously to several bases in northern France between 1915 and 1919. In 1918/19, the Chaplin trio were doing “tremendous work at Rouen, where they were much loved”, according to Lena Ashwell, a key organizer of the effort.

We do not know what music they played, but Ashwell’s story suggests that the soldiers’ favourites included familiar songs such as “Annie Laurie”, “Drink to me only with thine eyes”, and various old English catches – and ragtime. The trio also took part in a programme of instrumental recitals given for the medical staff of the hospitals on the army bases, and are recorded as having played at a Men’s Rally at the London Central YMCA in July 1918.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

The Beggar’s Opera and beyond

The year 1920 opened a new chapter in the Chaplin sisters’ lives, one which would consume much of their energy for many years. Nigel Playfair, actor-manager of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, in London, decided to mount a revival of John Gay’s 1728 Beggar’s Opera. Frederic Austin rewrote the opera from the eighteenth-century tunes, scoring it for “String Quintet, Flute, Oboe and Harpsichord, with occasional use of the Viola d’ Amore and Viola da Gamba”. Who better to play the historical instruments than the Chaplin Trio?

The revived Beggar’s Opera turned out to be a smash hit. It ran for three and a half years and 1,473 performances – several revivals brought the total number of performances to 1,704. As far as we know, the Chaplin sisters played in all of them. [There will be a later blog post about this production of the Beggar’s Opera.] Unsurprisingly, their concert programmes fell away during those years.

From 1924 on, however, the sisters resumed their early music concerts, such as “An Elizabethan evening with excursions into the 17th and 18th centuries” (February 1925), recitals of “old music” at the Steiner Hall (28–29 October 1927) and further “Ancient Dances and Music” programmes – interspersed, of course, with the re-runs of the Beggar’s Opera. At the age of 69, in March 1926, Nellie was introducing an Elizabethan programme and playing pieces by Byrd from Parthenia for the People’s Concert Society. The trio also featured on more than 30 radio programmes around Britain, and, no doubt, the sisters continued to teach.

Much of the information we have about the Chaplin sisters consists of concert programmes, announcements and reviews in newspapers and specialist music magazines, and newspaper radio listings. In themselves these make fairly dry reading, but they open up a fascinating window onto the world of English music-making and concert-going from the late Victorian period right into the 1920s – a world in which the remarkable Chaplin sisters played a significant part.

The work of Nellie Chaplin as harpsichordist and researcher, and her part in the revival of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century dances, will be discussed in the next blog post in this series.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Jeremy Barlow, who first mentioned the Chaplin sisters to Semibrevity; Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation; Professor Freia Hoffmann of the Sophie Drinker Institut in Bremen, who kindly shared her very extensive research; Sandy Mitchell; and Michael Mullen and Elizabeth Wells of the Royal College of Music

© Mandy Macdonald 2016 – All rights reserved

If you appreciate this blog post, please share this link //bit.ly/1OibW5t

with your friends.

Taphouse’s 1743 Hass clavichord. By kind permission of the Bate Collection, Faculty of Music, University of Oxford. Copyright © 2016 T.W. Taphouse and early keyboards

In 1857, when he was aged just 19, Taphouse bought “a remarkably fine harpsichord by Shudi and Broadwood [made in 1773]” which “led me to take an interest in the history and development of keyboard-stringed instruments”. It made only 13 shillings (currently 65 pence!) at an estate auction in Banbury; Taphouse paid the purchaser £2. 10 shillings and sold it on to Messrs. Broadwood in London for £15.

In the same year, Taphouse met A.J. Hipkins (a well-known authority of the time on the piano and its predecessors, and author of several books and 134 articles in Grove), who “gave me many valuable hints upon the restoration of old instruments”, and with whom he corresponded for “upwards of forty years”.

Taphouse restored several keyboards, which he subsequently lent out for lectures and concerts, and displayed (with various rare scores, books and other instruments) at large events, such as the International Inventions Exhibition, 1885; the Musical and Art Exhibition at the Royal Aquarium, 1892; and the Music Loan Exhibition, celebrating the tercentenary of the Worshipful Company of Musicians, held at the Fishmongers’ Hall in 1904.

Although he is known to have been a pianist and church organist, there is no record of him ever having played the harpsichord in public. His step-daughter, Nellie Woodward-Taphouse, however, was “an excellent performer of the harpsichord [and clavichord], having made it a special study”. She gave concerts from at least 1894, and a critic from the Musical Times wrote, “We fervently hope Miss Taphouse will let us hear more of these beautiful old instruments and their truly lovely music on future occasions.” Her obituary (she died, aged 39, in September 1908) also mentions that “She was closely and skillfully associated with Misses Chaplin in their concerts of Ancient Music and Dances …”

Detail of the 1743 Hass clavichord. By kind permission of Tricia Neal. Copyright © 2016 Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

Aptly, the Bate Collection, in Oxford now has three of Taphouse’s most admired instruments: a superb Shudi & Broadwood two-manual harpsichord of 1781 (listen to it here), a beautiful little spinet by John Harrison of London dated 1749 (listen to it here), and a magnificent five-octave clavichord by Hieronymus Albrecht Hass built in 1743 (listen to it here).

Other instruments owned by Taphouse:

Harpsichords:

- A 17th-century Italian “clavicembalo, compass 3 and 6/8 octaves, C to E, two stops, enclosed in a white painted deal case, and containing an oil painting of Pan on the lid, 5ft. 9 by 2ft. 6, complete on three pedestals”. According to the late Margaret Campbell, in Dolmetsch: The Man and his Work, this instrument was restored by AD in 1894; it’s unknown from whom Taphouse obtained it.

- Jacob Kirkman two-manual (1744), now in private ownership, on permanent loan to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. See here for photos and details.

- Jacobus and Abraham Kirkman two-manual (1775), lent to Nellie Chaplin from 1904. This may have been the instrument which Gustav Leonhardt bought from Raymond Russell in 1957.

Spinets/ Virginals:

- Italian pentagonal spinet, 16th century, compass 4 octaves and 1 note, E to F. “The case is decorated with floriated designs in black, and a number of small ivory nobs or buttons.” It has no maker’s name, but is (according to an exhibition catalogue) exactly similar in size and shape to one by Marcus Jadra, dated 1568, in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

- Italian Virginals c. 1600, “in the original wooden case”.

- 17th-century Italian “Spinetta of 3 and 5/8 octaves, with a decorated case”.

- Three more spinets by Charles Haward (1683), Edmund Blunt (1703), and Joseph Baudin (1723).

Clavichords:

- Nicola Palazzi clavichord (1749).

- A five-octave unfretted clavichord by Johann Gotthelf Hoffmann (1784), now at Yale University. See below.

- Clavichord by Joh. Paul Kraemer und Soehnen (1803),

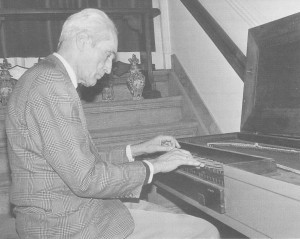

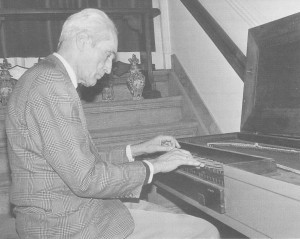

Gustav Leonhardt and the Kraemer clavichord in 1998. By kind permission of Jan Raas. Copyright © 2016 previously owned by Carl Engel (1818–1882), much of whose famous instrument collection went to the South Kensington (now Victoria & Albert) Museum. This clavichord later belonged to Cecil Clutton, who bequeathed it in 1991 to Gustav Leonhardt; it is now in the possession of Menno van Delft, who had it restored in 2015.

Square pianos (interestingly, no grands):

- Johannes Zumpe (1767)

- Pohlman (1769)

- Broadwood (c.1780) with a compass of only 3 octaves

- Broadwood (1796)

As Taphouse was actively collecting for almost 50 years (apart from possibly having taken old instruments in part-exchange for pianos from his flourishing music shop), we may safely assume that many more early keyboards passed through his hands than those listed.

If you know the current location of any of the instruments mentioned above, please let us know, via the comments box

Harpsichord music

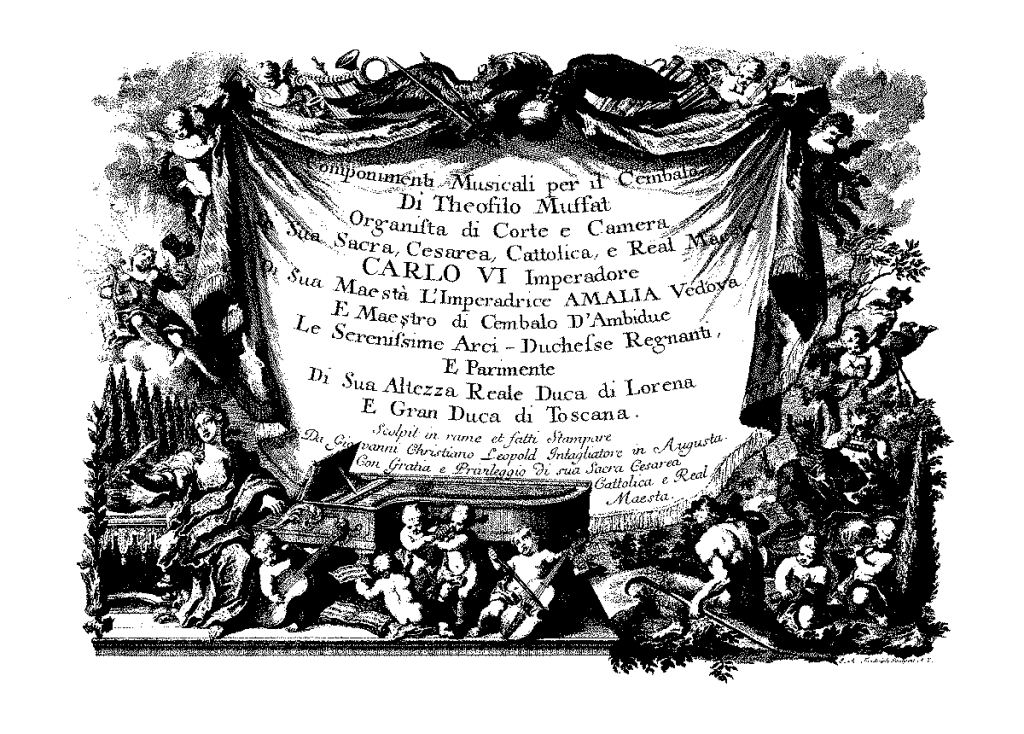

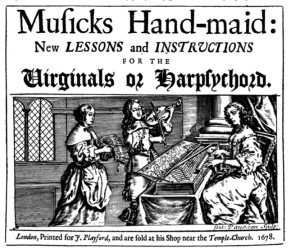

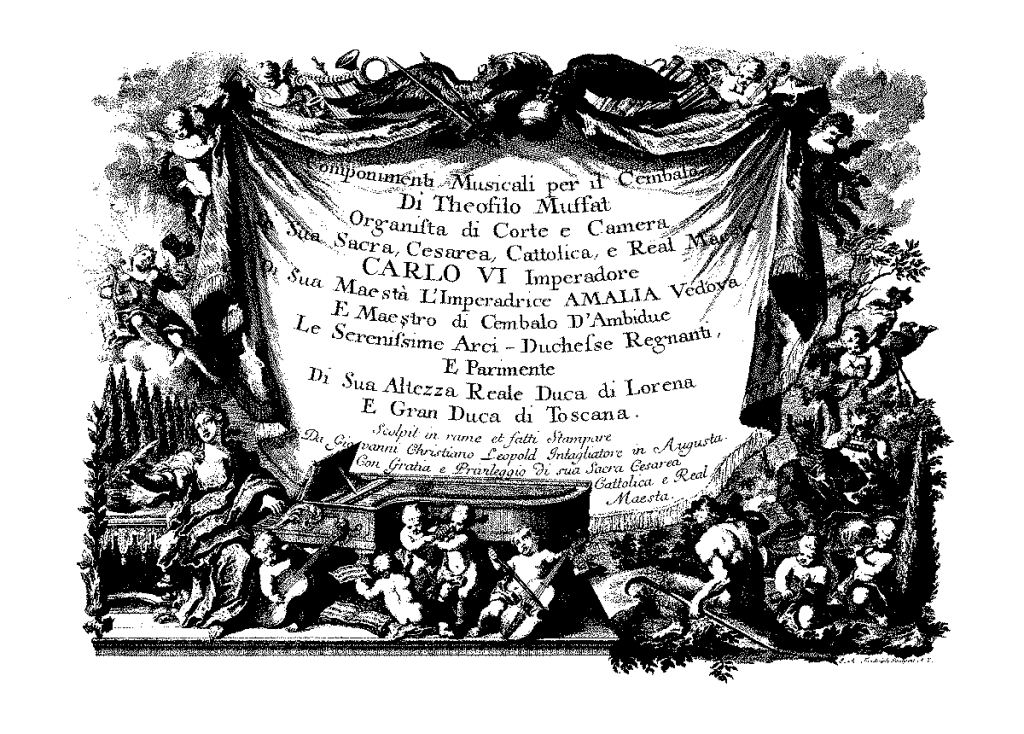

Gottlieb Muffat – “Componimenti musicali per il cembalo” (1739, described by the composer as “the most beautiful product to be met with in all of Germany”; it was certainly one of the most lavish examples of 18th-century music printing. Taphouse’s library contained 195 volumes of manuscripts and early editions of harpsichord music, including more than a yard of shelf space of sonatas, suites and “Favourite Lessons”, along with the following titles:

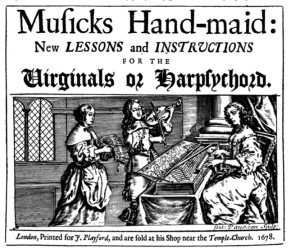

Charles Burney’s copy (apparently unique) of Mattheson’s Pièces de clavecin … en deux volumes (1714); a manuscript Harpsichord Book from the harpsichord maker, Jacob Kirkman; D’Anglebert – Pièces de Clavecin; Charles Avison – 8 Concertos; F. Couperin – Pièces de Clavecin, 2 vols. (1713); Frescobaldi – Toccate d’intavolatura (1637); Froberger – Toccate, canzone … (1693); Krieger’s Anmuthige Clavierübung … (1699, “autograph of J.S. Smith” [sic] probably J.C. Smith, Handel’s amanuensis); Byrd, Bull and Gibbons – Parthenia (1655); Gottlieb Muffat – Componimenti musicali per il cembalo (1739); John Playford – Musick’s Hand-maid: New Lessons and Instructions for the Virginals or Harpsichord;  Purcell – A Choice Collection of Lessons (1696); Rameau – Pièces de clavecin en concerts (1741); and a taste of the exotic, in the form of The Oriental Miscellany … favourite Airs of Hindoostan adapted [by William Hamilton Bird] for the harpsichord (Calcutta, 1789), recently recorded on a Kirkman by Jane Chapman. Purcell – A Choice Collection of Lessons (1696); Rameau – Pièces de clavecin en concerts (1741); and a taste of the exotic, in the form of The Oriental Miscellany … favourite Airs of Hindoostan adapted [by William Hamilton Bird] for the harpsichord (Calcutta, 1789), recently recorded on a Kirkman by Jane Chapman.

Taphouse also owned the two parts of Diruta’s Il Transilvano (in editions from 1625 and 1622); Couperin – L’art de toucher le clavecin (1717, acquired at least thirteen years before Dolmetsch got his copy, on his 45th birthday in 1903); Locke’s Melothesia (1673) and 15 other thorough-bass tutors. His unique copy of “Richard Aylward’s curious MS. book of lute and harpsichord music” (c. 1640, now lost) was mentioned in a warm appreciation of Taphouse and his “rich collection”, in the preface of Edward Dannreuther’s Musical Ornamentation (1893).

When Arnold Dolmetsch burst onto the early music scene in the 1880s, Taphouse had already been collecting for more than 20 years. We don’t know much about their relationship, other than the fact that AD exchanged a “precious little book” (we don’t know what) for a five-octave unfretted clavichord made by Johann Gotthelf Hoffmann in 1784, which he subsequently sold during his American stay to the heiress, Belle Skinner, for the astronomical price of $1,000.

There may also have been other trades between them, but there is no record of them.

Arnold Dolmetsch and his Bressan recorder. By kind permission of the Dolmetsch Trust. Copyright © 2016

When Taphouse’s collection came up for auction in 1905, Dolmetsch was initially interested in buying a virginals which, ultimately, he found too expensive, at £12. Via a Mr Thompson, he did buy, for £2, a recorder (in lot 111, with two flageolets) which was erroneously catalogued as being made by “Barton”, but was actually a treble recorder of c. 1730 (now in the Horniman Museum) by Peter Bressan (1663–1731), on which Dolmetsch was to base the instrument that started a revolution.

From the book sale, he obtained a recorder tutor: the Compleat Flute Master (1695), which he desperately needed in order to learn to play the Bressan properly. According to the auctioneer’s ledger, previously overlooked, this was bought on AD’s behalf by Beatrice Horne, a viol-playing friend and a very generous benefactor (see Campbell), as AD was on the boat to the USA at the time the auction was held.

Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation has recently found a diary entry for an appointment with Miss Horne on 20 October 1910, on his return from America, and has suggested that the Compleat Flute Master changed hands then. This would explain why AD did not play the recorder in public till a concert in Perth in 1912. Dr Blood has written about all this in the Autumn 2015 issue of the Foundation’s Bulletin.

Summing up

As well as his post-mortem influence on the career of Arnold Dolmetsch, Taphouse played an important role in the revival of the harpsichord and clavichord and, like Carl Engel before him, no doubt saved many instruments from being broken up for firewood.

Unfortunately, Taphouse left no writings, other than the hand-written catalogue of his keyboard instruments and publications in his library relating to the history of the piano, that he made in 1890. It’s clear from these descriptions, and from the annotations he left in the books and scores he owned, that he was extremely knowledgeable and took the whole business of collecting very seriously. His library contained long runs of academic journals, contemporary books in German, Italian and French, and a wide range of bibliographical source material (such as auction and publishers’ catalogues), some of which he had bound together in 27 volumes.

Given the fame of Taphouse’s collection, it’s surprising that no attempt was made to keep it together. Of the 2,000-plus rare and unique items in his library, most have disappeared without trace. Apart from the haul at Leeds, the British Library has 14 items known to have belonged to Taphouse; the Bodleian has around 20; and the Library of Congress holds a single lot from the book sale, consisting of 23 bound volumes of assorted pamphlets and musical tracts.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Faye Belsey, Assistant Curator, Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford; Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation; Menno van Delft; Andrew Lamb, Curator of the Bate Collection; Thomas MacCracken; Gilly Margrave, Librarian (Music and Drama), Leeds Library and Information Service; Dr Rupert Ridgewell, Christopher Scobie and Claire Wotherspoon of The British Library; James L. Wallmann; and Dr Alexandra Williams, whose The Dodo was really a phoenix: the renaissance and revival of the recorder in England 1879–1941, has been a valuable source. You can download the whole thing (400 pages!) here.

If you appreciate this blog post, please share this link //bit.ly/1ZsLfHb with your friends.

Copyright © 2016 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

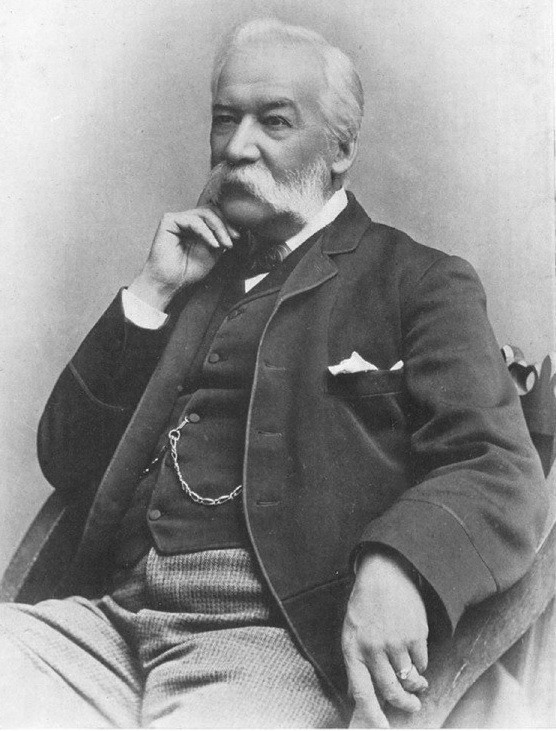

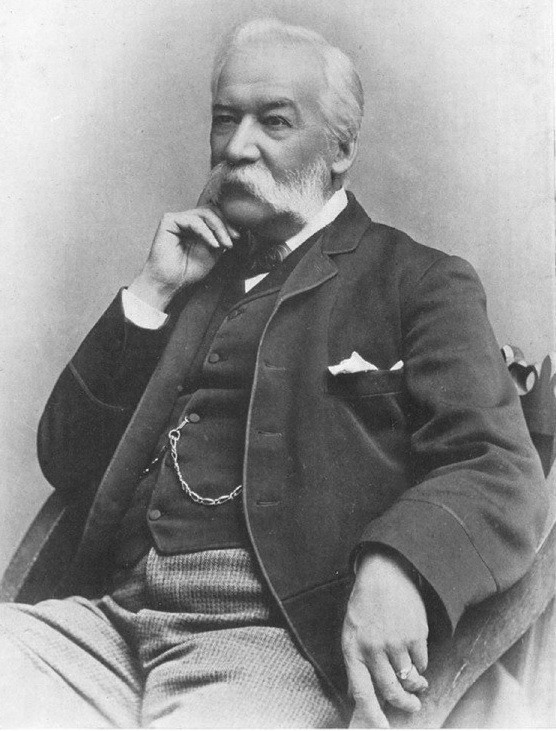

T.W. Taphouse, “a special [photographic] portrait, true to life” from the Musical Times, October 1904

The funeral of Thomas William Taphouse (1838–1905), Mayor of Oxford, which took place “amid many manifestations of sorrow”, was reported in the Court Circular of The Times as “a very large and representative gathering”, attended by several MPs, along with five presidents of Oxford Colleges and all the members of Oxford’s town council. “The procession was of great length … and there was a general closing of shops while the funeral was taking place. So numerous were the floral tributes that they were conveyed in a special [extra] carriage.”

The obituary in the Musical Times spoke of a genial, modest, kind-hearted man, and it’s clear that Taphouse was, by all accounts, a jolly good fellow, and a friend to many, and that he would be sorely missed (not least by the editorial staff of the MT, with whom he had, apparently, regularly collaborated).

Taphouse left school at the age of 14 and was apprenticed to his father, who was a cabinet-maker and furniture-broker. Four years later he left for London to learn the “science of piano-tuning”. On 4 April 1857, he established a music shop, with his father at 10 Broad Street, Oxford. Following a major fire, the business moved to 3 Magdalen Street in September 1858, and C. Taphouse & Son Ltd. was to remain at these premises for the next 124 years.

Described in the census simply as a piano-tuner, Taphouse spent the next 30 years travelling around Oxford with a pony and trap, but he was to become a very wealthy man during this period. For whatever reason, he did not begin his career in local politics until the age of 50, and was elected mayor of Oxford in 1904.

Although his municipal endeavours, particularly those relating to buildings and art works, were mentioned by the Public Orator when he was awarded an honorary MA from Oxford University, also in 1904, it was largely for his “research into old English music” and his discovery of several unknown works, not least Purcell’s “The Queens Funerall March sounded before her Chariot [sic]” and the “Canzona, as it was sounded in the Abbey after the Anthem”, a now famous piece written for the funeral of Queen Mary in 1695.

This was the first time ever that the award – a distinction “as unique as it was deserved” – had been conferred on a tradesman of the city, and it also recognised his “large-hearted unselfishness”, as “he always delighted to place his wide knowledge … , experience and the treasures of his library at the disposal of [others] …”

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

“One of the finest music libraries in the country”

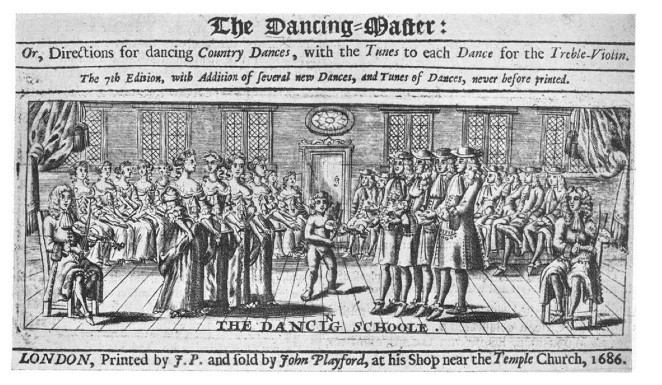

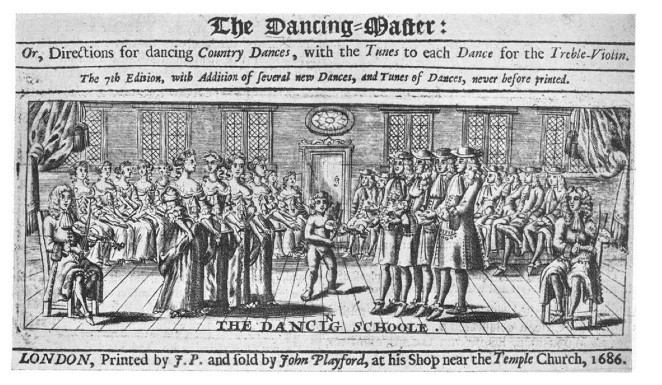

Taphouse’s first purchases took place in 1858 (when he was just 20), when he bought the third edition of Playford’s Dancing Master, in Bath, for sixpence, Morley’s Plaine and Easie Introduction (1597) for 15 shillings, and Mace’s Musick’s Monument (1676), with the portrait, for 25 shillings.

By the time of his death he had amassed more than 2,000 volumes; but many items were sold in unspecified mixed lots and “bundles” at a two-day Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge’s auction in July 1905, so the exact content of his library is not known. There were 876 lots, which made a total of £1062.

Collecting obsolete instruments and old music books is certainly an unlikely hobby for a young man, and why he embarked on it is unknown. In an interview, just a few months before his death, he said that he was “encouraged” in his “hobby” by several eminent collectors of the day, including the composer and organist, Sir John Stainer, who was also Heather Professor of Music at Oxford; noted Bach expert, Sir Walter Parratt, who became Queen Victoria’s Master of the Queen’s Musick in 1893; and Sir Frederick Ouseley, whose own library (now in the Bodleian, Oxford) contained Handel’s conducting score from the Dublin premiere of Messiah.

Described by Alex Hyatt King as “ that enterprising collector”, Taphouse combined discernment, the broad knowledge of a self-taught expert, very wide interests (with a penchant for 18th-century and earlier items), and significant financial resources.

He was particularly keen on Purcell and owned around 20 items, including the very rare Sonnata’s [sic] of III Parts (his first publication); Diocletian [sic] 1691, The Tempest; and a large manuscript collection, lost and only recently found (see Holman in Early Music vol. 40, no. 3), containing the unique copy of the so-called “Violin Sonata in G minor” Z780.

There was also a lot of Playford, often in multiple editions, including The Division Violist (1659), sold for £2. 6 shillings; Introduction to the Skill of Musick (1664); Musick’s Delight for the Cittern (1674); Harmonia Sacra (1688); and Simpson’s Compendium of Practical Musick in 5 Parts, together with Lessons for the Viols (1677). There was also a lot of Playford, often in multiple editions, including The Division Violist (1659), sold for £2. 6 shillings; Introduction to the Skill of Musick (1664); Musick’s Delight for the Cittern (1674); Harmonia Sacra (1688); and Simpson’s Compendium of Practical Musick in 5 Parts, together with Lessons for the Viols (1677).

Taphouse had a small but important collection of early editions of madrigals: Thomas Morley’s Madrigalls to Foure Voyces, The First Booke (1594); the part-books of his Canzonets, second edition (1606), sold for £21. 10; John Bennet — Madrigalls to foure voyces newly published … his first works (1599); and Thomas Weelkes – Madrigals of 5 and 6 parts, apt for the Viols and voices (1600) and Ayeres or Phantasticke Spirites for three voices (1608). From the same period, he owned a copy of the very rare Briefe Introduction to the Skill of Song (1596) by William Bathe.

Books on history, biography and travels accounted for a total of 343 volumes; church-music-related items and psalmody numbered 129. The collection was also rich in early theory, with 98 volumes, including Nemorarius – In hoc opere contenta … (1496), the first treatise on mathematics in music; Chas. Butler’s Principles of Musik in Singing and Setting (1636); and Prattica di musica (1596) by Zacconi.

Lot 582 in the book and music auction, “A Collection of 69 original vocal and instrumental pieces, autograph scores, by S. Bach [presumably J.S.], Benda, Dr Blow, Dragonetti, Palestrina, Scarlatti, S. and C. Wesley and others”, is an example of one of the unspecified lots, which was sold for only £3.

In the end, Leeds Public Libraries bought 143 lots, book dealers snapped up a further 323 lots and known private collectors, such as W.H. Cummings, Frank Kidson, and “Daddy” Mann, of King’s College, Cambridge, bought around 60 lots, leaving 350 lots unaccounted for.

This collection was mentioned in the first edition of Grove, and it is in the current, online version that Taphouse’s library is noted as being “one of the finest”.

The musical instrument collection

At the time of the Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge instrument auction (7 June 1905), the most usable antique keyboard instruments were retained by Taphouse’s harpsichord-playing step-daughter, Nellie Woodward-Taphouse. It’s unknown to what extent other choice items were kept by the family.

The instruments listed in the sale catalogue are rather a hotchpotch, and include six recorders (for details of “that” Bressan, see part 2 of this article), four oboes, a violin and viola (previously owned by the University Music School) made by William Baker of Oxford in 1683, six English citterns, six lutes, three viols (one each from France, Germany and Italy), miscellaneous brass instruments, an early serpent, several bagpipes, mandolins, eleven single and double flageolets and an Epinette des Vosges. Taphouse seems to have bought simply whatever caught his eye, which accounts for the fourteen flutes (German, made of ivory, and in the form of walking sticks) and the eight dancing-master violins that appeared in this sale.

He certainly didn’t have the systematic approach of Canon Francis W. Galpin (1858–1945), whose first collection – started in the 1870s – representing 2,000 years of music-making in 562 items, ended up in the Boston Museum of Fine Art in 1917, as no British institution was interested in acquiring it.

The instrument sale consisted of 125 lots, amounting to 200 items, including 80 non-European instruments, which made a total of £230. 4 shillings.

A further 41 instruments, originally owned by Taphouse – including an old English five-string tenor viol, which was converted to a four-string by a travelling gipsy – are currently housed at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford.

More next time.

If you appreciate this blog post, please share this link //bit.ly/1OhQmyr with your friends.

Copyright © 2015 Semibrevity – All Rights Reserved

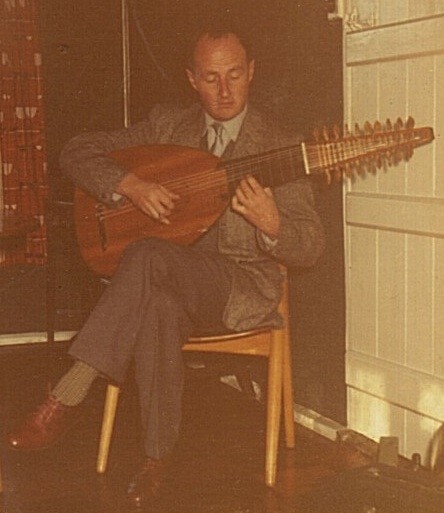

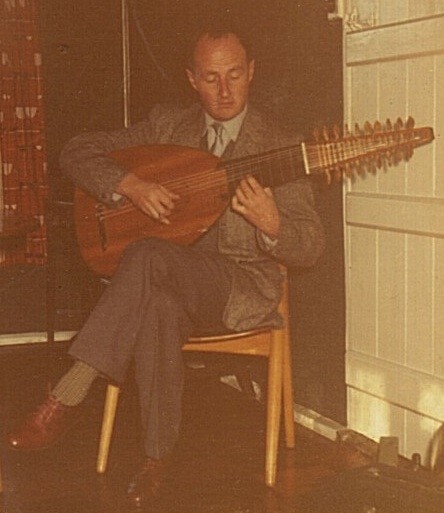

Hopkinson Smith and Desmond Dupré, in France in 1972 This blog post is an augmented version of the article by Anne Pimlott Baker published in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, reproduced here with the kind permission of Oxford University Press. Additions to the text are in blue type or square brackets.

Desmond John Dupré (1916–1974), lutenist, guitarist [and viol player], was the third child of Frederick Harold Dupré, analytical chemist, and his wife, Ruth Clarkson, a violinist. He was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School, London, and won a scholarship to St John’s College, Oxford, in 1936, graduating with a first in chemistry in 1940. A conscientious objector, he spent the war as a research chemist in the Glaxo laboratories, where he worked on penicillin.

Dupré had always wanted to be a professional musician, and [aged 30] he studied the cello at the Royal College of Music (1946–8). He was taught there by Ivor James and Herbert Howells. When he became interested in early instrumental music [while still at the RCM] he turned to the guitar, which he had played since he was a child, in order to play the lute repertory, and he also taught himself to play the viol. For a few months in 1946 he gave guitar lessons to the thirteen-year-old Julian Bream.

Julian Bream remembers (in conversation with Thea Abbott, 2 July 2015):

They weren’t conventional lessons, rather they were coaching sessions. We played duets on our guitars and he took me through a tutorial book (Roch’s School of Tárrega: A Modern Method for the Guitar) which was very good for me. He encouraged me to see my practice as a discipline rather than just an opportunity to learn new pieces. When I left my lessons with [Dr Boris] Perott I was in a hell of a state and having to relearn everything, Desmond rebuilt my confidence, he listened to me, suggested improvements in my technique. We only had about four or five sessions together, but it was great … Desmond played an old Panormo, gut strung, and he played with the flesh – not nails. His playing had great charm and he made a good sound, relaxed and evocative.

We stayed friends and he played gamba [cittern and lute] as a member of the Julian Bream Consort, and we made many broadcasts and recordings together over the years.

In 1948 Dupré joined the Boyd Neel Orchestra, [the first modern] chamber orchestra, as a cellist, but he left in 1949 to devote himself to the guitar [and, apparently, he never played the cello again.]

Alfred Deller

Deller and Dupré, in their early days Deller met Dupré in 1947 through the Reverend Duncan Thomson, a fellow-alto at St. Paul’s Cathedral, who had heard Dupré playing Dowland on the guitar, and suggested that the two might work together.

They formed a duo […] and, at first, he played the lute parts of the Dowland lute-songs on the guitar. When [in 1948] Deller formed the Amphion Ensemble (which became the Deller Consort in 1950), Dupré was one of the instrumentalists, playing the guitar and viola da gamba.

In 1951 Dupré asked Maurice Vincent to make him a lute [based on the dimensions of Diana Poulton’s instrument] and taught himself to play it in time to accompany Deller on 28 May 1951 at one of a series of recitals of English song at the Wigmore Hall, London, as part of the Festival of Britain.

According to his student, the American lutenist, Hopkinson Smith, he just “figured it out for himself” without reference to any historical treatises!

He and Deller gave recitals all over the country, including favourite Dowland lute-songs such as ‘I saw my lady weep’, ‘Can she excuse my wrongs’, and ‘Come away sweet love’, and the programme always included lute solos such as fantasias by Dowland: Dupré made skillful arrangements of all the songs and solos for their performances.

He made the first of his many recordings [see this discography] with Deller in 1950, performing two Dowland songs [on the guitar]. Here is that 78 rpm record:

Their first long-playing record was Shakespeare Songs and Lute Solos in 1955. Here is a track from that disc:

Dupré continued to perform and record with Deller for the rest of his life, touring the world with the Deller Consort and teaching at the Deller Academy, Deller’s summer school in Provence.

After his death Deller wrote:

It is impossible for me to imagine how my career would have developed without his scholarly help and superb gifts as an accompanist … [I] never doubted, even in my most wayward moments that he would be right on cue for the final cadence.

Mark Deller added that he “was delightful to work with, and the most sensitive (if not overtly demonstrative) of players.”

Dupré played an important part in the revival of interest in early music and especially in the restoration of the lute, an instrument that had disappeared from the end of the eighteenth century until Arnold Dolmetsch began to make and play lutes [in the 1890s]. After Dolmetsch’s death in 1940, the only professional lutenist in England was Diana Poulton, a former pupil […].

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

The Lute Society

Dupré attended the inaugural meeting of the Lute Society on 20th October 1956, at which he supported the publication of music in tablature.

At the conclusion, he gave the Society’s very first recital, consisting of Dowland’s, Frog Galliard, Fantasy and Lady Clifton’s Spirit; Francis Cutting’s Variations on Walsingham, Dowland’s Shoemaker’s wife; Robert Johnson’s Toy and Robinson’s Variations on Go from my Window.

He was the first president of the Lute Society, from 1965 to 1973 [having been proposed by Ian Harwood, seconded by Robert Spencer and elected nem con.]

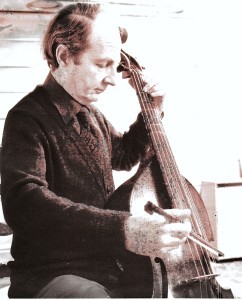

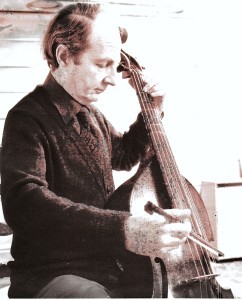

Dupré and the viol

At the time that Dupré was teaching himself to play the viola da gamba in 1946/7, the only other professional gamba soloist in the UK was the now completely forgotten Ambrose Gauntlett (1889 – 1978), who was also the principal cellist of the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

The “small (but growing) body of devoted [Dolmetsch viol] students”, mentioned by the music historian Percy Scholes in 1938, still existed no doubt, but they were not much in evidence outside Haslemere. Speaking of which, the Observer critic, Charles Stuart, announced the 21st Dolmetsch Festival in July 1946 as follows: “These are pleasant and passionless occasions [with the] gilded plangency of the harpsichord, [and] the amiable lowings of viola da gamba and violone.”

Apart from appearances with Alfred Deller, Dupré played only once at the Festival, on the tenor viol, in a concert in 1953.

In terms of his instruments, Dupré’s son, John, wrote:

Desmond Dupré playing the 1688 Shaw Sadly I no longer have my father’s gamba … however, I do remember it with great pleasure. It was made by John Shaw, in 1688, at the Harp and Hoboy in the Strand, according to the label. This was certainly the instrument he loved best (it had a wonderful bass register), though he did have other antique instruments at various times, including a [1692] Barak Norman bass and a [Henry] Jaye treble [from 1630]. As far as I can recall he had no modern instruments except a tenor. He very rarely played anything but the bass.

In May 1948 he played in the first London performance of Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppea, at Morley College (with Deller singing the role of Ottone), and he would often include viola da gamba pieces in his recitals with Deller.

In performances of Bach’s St John Passion, he frequently played both the lute solo accompanying the bass aria ‘Betrachte, meine Seele’ and the obbligato viola da gamba part accompanying the alto in ‘Es ist vollbracht’, and he gave the first of many performances of the viola da gamba part in Monteverdi’s Vespers at King’s College, Cambridge, in July 1951 as part of the Festival of Britain.

Other formations

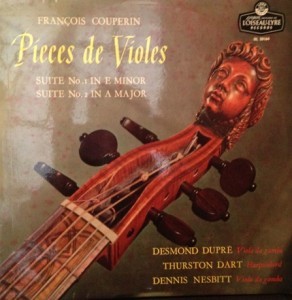

Dupré formed lasting partnerships with other artists, most notably Thurston Dart, with whom he first played in 1949. The two men performed and recorded Bach’s gamba sonatas and Dart’s reconstruction of Handel’s Concerto for lute and harp Op. 4 No. 6 [with Philomusica].

As members of the Jacobean Ensemble, Dart and Dupré broadcast frequently, with a line-up which included Neville Marriner, Peter Gibbs or Carl Pini (violins), and sometimes gambist Dennis Nesbitt. They made several discs, of Jacobean Consort Music, Purcell’s Sonatas (in 3 and 4 Parts), some Louis Couperin, Les Nations by Francois Couperin and his Pièces de Violes, which you can listen to, by clicking the link on the left.

From 1947 Dupré played bass viol and guitar in the Old Music with Old Instruments Consort with Eric Marshall Johnson (lute, viola d’amore); his wife, Cecily Arnold (soprano, virginals) and Edgar Hunt (recorder, treble viol).