A Kirkman harpsichord from 1755, similar to that used by Nellie Chaplin. By courtesy of Musical Instrument Museums, Edinburgh (MIMEd 4330).

By Guest Blogger: Mandy Macdonald

The fascination of old instruments

The use of historical instruments contributed greatly to the charm of the concerts given by the Chaplin sisters and drew in audiences. Both Nellie and Kate owned eighteenth-century instruments. Nellie’s first instrument was a Jacobus and Abraham Kirkman of 1775, which she had on loan from Nellie Woodward-Taphouse, step-daughter of the Oxford musical instrument dealer and collector T.W. Taphouse; in 1908 she bought another Kirkman (this time, by Abraham and Josephus), with two manuals, 2 x 8’, 1 x 4’, buff and machine stops, dated 1789 – though she blithely modified it in a way we might think irresponsible today, by having the Venetian swell removed.

[In 1916 Nellie “came across” another Kirkman harpsichord originally made in 1766 for Princess Amelia, the youngest daughter of George III, which had been given as a 16th-birthday present in 1874 to Ellen Willmott, the famous amateur botanist. This instrument, which was always called the “Princess”, was lent to Nellie, who paid for its refurbishment. According to the correspondence between them, it was helpful for her to have two instruments due to her many engagements.]

Listen to a sound clip of the 1755 Kirkman (at the bottom of that page)

Pictures and technical details of another Kirkman harpsichord, with a Venetian swell.

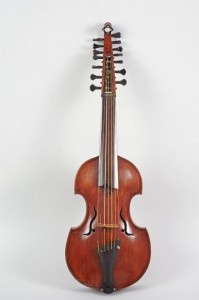

A viola d’amore made by George Saint-George in 1912, similar to one used by Kate Chaplin. By courtesy of Musical Instrument Museums, Edinburgh (MIMEd 4080).

Around 1906, at the suggestion of Nellie’s friend, the London-domiciled Belgian cellist, musicologist, and writer, Edmund van der Straeten (1855–1934), Nellie’s younger sisters began to learn instruments more in keeping with the timbre and volume of the harpsichord. Kate was taught the viola d’amore by George Saint-George (1841–1924) a virtuoso player, composer, and skilled luthier, who built an instrument for her. In 1925 we find her playing Saint-George’s arrangement for the viola d’amore of “The Irish Ho-Hoane”, from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.

Video clip of Thomas Georgi playing the opening ritornello and first solo from Vivaldi’s Concerto for viola d’amore, RV 392 (minus the orchestra!), so you can really hear the amazing resonance of this instrument. See also his fascinating site.

Mabel, the cellist, was to start the bass viol, taking lessons from Van der Straeten, who himself was an important viol pioneer, and he tells us that she became “in a very short time an excellent player on that difficult instrument”. Mabel owned a highly decorated six-string viola da gamba (see here and below) made in 1718 by Barak Norman (c.1670 – c.1740), which is now in the possession of the Smithsonian Institution.

Listen to Jordi Savall playing Forqueray on a 1697 Barak Norman viola da gamba

The instruments themselves became a talking point for audiences and reviewers of the Chaplin Trio’s performances. In November 1912, for example, a much-reported concert of music from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, given at London’s Aeolian Hall in aid of the Shakespeare Memorial Fund, included Bach’s D minor triple concerto – possibly its first modern British performance – played on three harpsichords dated 1775, 1782 and 1789 (the latter presumably the one belonging to Nellie). “The effect of this old-world music on the three old-world instruments was enchanting”, the reviewer rhapsodized.

His comment is fairly typical of reviewers’ reactions to the Chaplin “product”, which was regularly described as “quaint”, “charming”, even “fragrant”; but the reviewers also often thought the sound of the Baroque instruments “thin” and weak – which it probably was, given the size of the concert halls that they were expected to fill and the fact that they seem often to have been used in conjunction with modern instruments.

A reviewer of one of the very first revival concerts (December 1904) wrote almost apologetically:

… the quaint old instruments of the time, the clavichord, spinet and harpsichord, … in spite of their thin and, to modern ears, possibly unfamiliar sound, still remain the proper instruments for the true interpretation and the delicate charm of the music of the period.

The problem persisted throughout their careers: as late as October 1927, a Times reviewer noted, even while applauding the performance’s approach to historical accuracy:

a slight difficulty arises from the faint tone of the harpsichords used by Miss Chaplin, which are Kirkmans of the eighteenth century … there is no gainsaying the fact that owing to the difficulty of clear hearing among the players the ensemble was faulty.

Nonetheless, by 1913 the trio’s “Ancient Dances and Music” shows were being described as “fashionable”, and they became something of a “brand”: the combination of dance and music and the novelty of the historical instruments made them highly popular with audiences, and the trio, led by Nellie, repeated the format again and again from 1905 right into the 1920s, around the country and on radio.

“Modern troubadours” at the battle front

During the first world war the trio were among 600 performing artists who formed “concert parties” to give entertainments to the troops in France. This support to the war effort was organized, somewhat surprisingly, by the Women’s Auxiliary Committee of the YMCA in London, and concert parties were sent out more or less continuously to several bases in northern France between 1915 and 1919. In 1918/19, the Chaplin trio were doing “tremendous work at Rouen, where they were much loved”, according to Lena Ashwell, a key organizer of the effort.

We do not know what music they played, but Ashwell’s story suggests that the soldiers’ favourites included familiar songs such as “Annie Laurie”, “Drink to me only with thine eyes”, and various old English catches – and ragtime. The trio also took part in a programme of instrumental recitals given for the medical staff of the hospitals on the army bases, and are recorded as having played at a Men’s Rally at the London Central YMCA in July 1918.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

The Beggar’s Opera and beyond

The year 1920 opened a new chapter in the Chaplin sisters’ lives, one which would consume much of their energy for many years. Nigel Playfair, actor-manager of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, in London, decided to mount a revival of John Gay’s 1728 Beggar’s Opera. Frederic Austin rewrote the opera from the eighteenth-century tunes, scoring it for “String Quintet, Flute, Oboe and Harpsichord, with occasional use of the Viola d’ Amore and Viola da Gamba”. Who better to play the historical instruments than the Chaplin Trio?

The revived Beggar’s Opera turned out to be a smash hit. It ran for three and a half years and 1,473 performances – several revivals brought the total number of performances to 1,704. As far as we know, the Chaplin sisters played in all of them. [There will be a later blog post about this production of the Beggar’s Opera.] Unsurprisingly, their concert programmes fell away during those years.

From 1924 on, however, the sisters resumed their early music concerts, such as “An Elizabethan evening with excursions into the 17th and 18th centuries” (February 1925), recitals of “old music” at the Steiner Hall (28–29 October 1927) and further “Ancient Dances and Music” programmes – interspersed, of course, with the re-runs of the Beggar’s Opera. At the age of 69, in March 1926, Nellie was introducing an Elizabethan programme and playing pieces by Byrd from Parthenia for the People’s Concert Society. The trio also featured on more than 30 radio programmes around Britain, and, no doubt, the sisters continued to teach.

Much of the information we have about the Chaplin sisters consists of concert programmes, announcements and reviews in newspapers and specialist music magazines, and newspaper radio listings. In themselves these make fairly dry reading, but they open up a fascinating window onto the world of English music-making and concert-going from the late Victorian period right into the 1920s – a world in which the remarkable Chaplin sisters played a significant part.

The work of Nellie Chaplin as harpsichordist and researcher, and her part in the revival of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century dances, will be discussed in the next blog post in this series.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to Jeremy Barlow, who first mentioned the Chaplin sisters to Semibrevity; Dr Brian Blood of the Dolmetsch Foundation; Professor Freia Hoffmann of the Sophie Drinker Institut in Bremen, who kindly shared her very extensive research; Sandy Mitchell; and Michael Mullen and Elizabeth Wells of the Royal College of Music

© Mandy Macdonald 2016 – All rights reserved

If you appreciate this blog post, please share this link //bit.ly/1OibW5t

with your friends.

Leave a Reply