PLEASE “LIKE” THE BLOG (ON THE RIGHT), & NOT JUST THIS PAGE

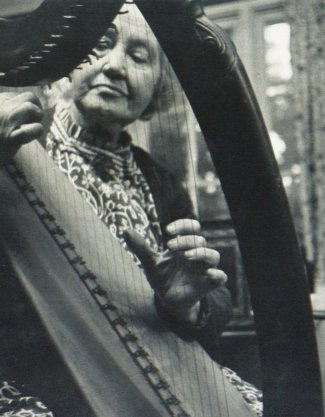

Mabel Dolmetsch, in later life

I’d been meaning to buy Personal Recollections of Arnold Dolmetsch (published in 1957) for ages, and finally it arrived just after the recent conference in the Netherlands on Gustav Leonhardt (report from organizer, Jed Wentz, to follow), in which one of the speakers described Arnold as an amateur!

This is, of course, not at all true, even in the most literal sense.

Although the book hardly mentions money, we know that Arnold charged fees for his violin teaching and frequently for his performances, and sold the instruments he made.

His loss-making project to popularize triangular harpsichords for £25, which he announced without making any calculations, showed “the buoyant optimism which (come what may) supported Arnold through fair weather and foul”. The outbreak of war in 1914 halted the influx of orders, allowing Arnold to adjust the price for what was to become a “very popular and serviceable instrument”.

As for the slight disparagement with which the word ‘amateur’ is so often loaded, a contemporary reviewer of Personal Recollections described Arnold’s place in music history like this:

“He was the first modern musician to have an unqualified faith in early instrumental music, and to put this faith into practice by performing it on its original instruments and in its original form, instead of doctoring it up for modern consumption with patronizing “improvements” of scoring and presentation.”

The author, Mabel Dolmetsch (1874–1963), was Arnold’s third wife, 16 years his junior, who had started taking violin lessons from him in 1896 and, within a year, had become part of the concert-giving “family”, mostly performing on the violone or the viola da gamba. At the same time, she worked as Arnold’s instrument-building assistant, as she’d been learning wood-working, on the quiet.

The book is crammed with detail – about journeys and concerts and how the rooms looked; the costumes worn by the children (who, from an early age sang, played or danced); the variable quality of the catering; explanations of who was related to whom, and how which musicians came to play which instruments and why. It’s all rather rose-coloured, and not much is made of Arnold’s fiery temperament or his bankruptcy.

Famous people

The narrative is quite stiff with famous names, reminding the reader that Arnold was something of a superstar, having played the clavichord for President Roosevelt. He was a friend of many, including the antiquarian Fuller Maitland (co-editor of the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book), Sir George Grove (of the Dictionary) and the pianist and composer Busoni (to whom Chickering – AD’s generous American employer – gifted a harpsichord).

His literary connections with W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw and others are much less well known (to find out about them, see this blog). There’s also his involvement with the Arts and Crafts crowd (you know, the “green harpsichord” and all that), with Arnold playing the virginals to William Morris, as he lay dying.

Violin lessons

Arnold’s first violin teacher was a gypsy (really!), who disappeared one day, taking with him a violin borrowed from Arnold’s father’s music shop. Later, Arnold studied with the famous virtuoso Henri Vieuxtemps at the Brussels conservatoire and followed this by enrolling at the Royal College of Music, in its opening year of 1882, where his teachers included Sir Hubert Parry for harmony and Henry Holmes for violin. He then became a rather over-qualified part-time violin teacher at Dulwich College, the posh boarding school.

Searching for repertoire for his newly acquired “honey-toned” viola d’amore, in the Reading Room of the British Museum, Arnold stumbled upon stacks of 16th and 17th century English music for viols, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Instrument-making

Arnold learned the family trade of piano-making in his father’s workshop and was a skilled cabinet-maker by the age of fourteen, when he made a mahogany-veneered chest of drawers which Mabel described as “so faultless that not a thing has been altered from that day till this”. It’s amusing that Arnold had to be reminded that he had these skills, as he’d just been playing music for a period of ten years, and had quite forgotten (reportedly) that he knew how to restore instruments.

The whole story of the loss of the Bressan recorder, on Waterloo station, is given here in detail, and young Carl wasn’t as remiss as suggested elsewhere, but was rather overtaken by events. Arnold believed that this instrument was the only surviving playable recorder and set about making a copy, which ultimately brought about a huge revival.

Reviews from 1958

In one review, Mabel is criticized for “provided little insight into her husband’s methods of recreating a lost art through research, the reconstruction of ancient instruments, or the performances in which his labor culminated”.

Another, kinder reviewer – who obviously knew the family well, and later wrote Mabel’s obituary – wrote that this book “will give much pleasure to those who knew and loved [Arnold] well … and convey a little of the remarkable atmosphere in which he worked, to those who did not”.

She ends by saying, “Mabel’s loyalty and her serenity had more to do with [Arnold’s] success than this modest story tells.”

Also of interest:

The Dolmetsch Family with Diana Poulton: Pioneer Early Music Recordings, volume 1 (See blog post) Recordings, mostly from the 1930s, of Arnold, his third wife, Mabel, their children and musical friends playing small ensembles and viol and recorder consorts by the Lawes brothers, Purcell, Dowland, Marais, Leclair and others. This CD is not available in record shops, but you can order it here.

Leave a Reply