Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp c.1960, by kind permission of P.A.X. Reintjens (from “Luister”, April 2000) © 2017

Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp (1906–2000) was one of the early Dutch pioneers of historically informed performance. He prepared editions from composers’ manuscripts and original printed sources and reintroduced the viola da gamba and violoncello piccolo into the musical life of Holland in the 1920s and 1930s.

What’s in a name?

As Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp himself appreciated that his name was a bit of a mouthful, he often shortened it to Carel Boomkamp, particularly when he was abroad. Jaap Schröder, who knew him well, told me that he would often say, “Let’s leave the lions at home today” (leeuwen is “lions” in Dutch).

The fifth of six children, he was born in Borculo, in the east of the Netherlands, where his father was a clergyman. He began playing the cello when he was eleven, and left school at the tender age of fifteen, to study in Paris with Gérard Hekking, who had been principal cellist of the Concertgebouw Orchestra from 1903 to 1914 (and was later to teach Tortelier and Gendron).

Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp in 1925 © 2017

Boomkamp returned to Holland in 1925 to become the solo cellist of the Haarlem Orchestral Society. Shortly after he turned twenty, he landed the same job with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, making him the youngest solo cellist in the history of that orchestra.

Speaking at a rehearsal, Willem Mengelberg, the Concertgebouw Orchestra’s conductor, told Richard Strauss, “He’s just out of the egg, but he plays the cello magnificently”. Not enjoying Mengelberg’s “heavy German pathos”, Boomkamp left in 1930 to work as a soloist, play a great deal of chamber music and teach at the conservatories of Amsterdam, Utrecht and The Hague where, from the late 1940s, he took the ensemble class with the harpsichordist Janny van Wering.

Boomkamp became interested in early music while still a teenage student in Paris, through studying the cello suites of Bach. He was surprised by all the very different editions that were available, and then came across a facsimile of Bach’s autograph, which was a revelation to him, and that was the beginning of his interest in “authentic” performance. At this time, he also “discovered” the works of Antoine Forqueray and Marin Marais and had copies made of the originals.

Please subscribe to this blog – in the top right corner – and receive notifications of new posts by e-mail. In terms of getting information, this is preferable to “liking” the blog (though you can do that too), as Facebook’s money-making system limits the number of people who see our news feed, to as little as 10% of the total sent!

The viola da gamba

Boomkamp taught himself to play the gamba in 1926 using the Tratado (1553) of Diego Ortiz and an antique viola da gamba borrowed from the private musical instrument museum of the wealthy banker Daniël Scheurleer, who lived in The Hague. Take the virtual museum tour here.

As this instrument “had a very light timbre and six strings”, he decided to have a heavier seven-string gamba, with a very large sound, built by the Amsterdam violin-maker, Max Möller Snr. Boomkamp explained:

At that time, in the St Matthew Passion, singers performed as if they were on the stage in La Traviata, so you couldn’t possibly balance that with a subtle [small] gamba sound. Also, everyone was used to the sound of the cello, so the way in which I played the gamba obbligati was a compromise. Back then, a large sound was everything, and the gamba sound that we now have would have just been considered to be a thin squeak.

Boomkamp first played the viola da gamba in the St Matthew Passion in 1929 in the first complete performance given in Holland, by the Dutch Bach Society in the Grote Kerk in Naarden. He continued with the Bach Society until well into the 1960s, and also played for performances with the Concertgebouw Orchestra after the war.

Listen to Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp play Marin Marais’s Le Tableau de l’Opération de la Taille (a musical description of a bladder operation) on the gamba (in 1963?)

Compare Boomkamp’s playing with the same piece performed by Coin and Hogwood (in 1992)

Teacher and researcher

Boomkamp taught for over 40 years, and his students included – as well as half of the cello section of the Concertgebouw Orchestra – Gustav Leonhardt and the cello superstar, Anner Bylsma.

Anner Bylsma remembers:

At the conservatory, [Boomkamp] introduced me to old bows and the old way of bowing, which, at that time, I didn’t do much with. However, later, when I came to play with Frans Brüggen [and Gustav Leonhardt] in 1960, these wise lessons were of enormous use to me.

Leonhardt learned the cello and gamba with Boomkamp from the age of ten, and was taught Marin Marais’s table of ornaments (sowing the seeds for what was to come later). He particularly liked playing the gamba with an old bow. When Leonhardt returned from Vienna, he accompanied his former teacher in several concerts.

Boomkamp was one of the first to understand the importance of bows in creating an “authentic” sound, and wrote about this in De klanksfeer der oude muziek … (The Sound Atmosphere of Early Music …) in 1947.

His research was based on the examination of manuscripts and early editions and his practical experience with early bows and the old musical instruments that he had started buying in the 1920s. A catalogue of his important and extensive collection (now, sadly, housed in a storage depot at the Gemeente Museum in The Hague) was published in 1971.

Repertoire and ensembles

Like many other pioneers, Boomkamp played standard repertoire along with early music, sometimes combining very different periods, and the gamba and cello, in the same concert. One extreme example was in December 1939, at the Concertgebouw, when he played Telemann’s Suite in D major for viola da gamba and strings (watch and listen) followed by the Cello Concerto No.1 by Saint-Saëns. (watch and listen)

In Holland, he was the first to play Haydn’s Cello Concerto in D authentically, with oboes and horns and a five-stringed violoncello piccolo. He also had a keen interest in contemporary music, introduced many new works and had several pieces specially written for him by Henk Badings, Johannes Röntgen, Anthon van der Horst, Rudolf Escher and Hendrik Andriessen.

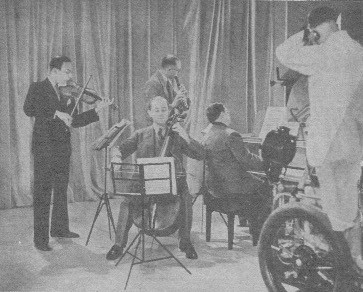

He was the gamba player and cellist of Musica Antiqua probably the first professional Dutch early music ensemble (active from 1935 to 1948),

Musica Antiqua, at the BBC, in 1937 © 2017

with the flautist Johan Feltkamp and the violinist Nicolas Roth (both from the Concertgebouw Orchestra), and with Erwin Bodky on the harpsichord. Their first BBC radio broadcast was in June 1937, when they were described as “seasoned Radio Hilversum performers”, and they made around 15 programmes, excluding the war years. They also performed at least once for the BBC’s new-fangled television, as the photo (used in a Concertgebouw programme) shows.

In 1938, Boomkamp formed a very famous, and short-lived, trio with Russian pianist Alexander Borovsky and Nicholas Roth, and he gave many concerts with the pianist Eduard van Beinum (who was also Mengelberg’s assistant).

He was a member of Alma Musica (1947–1964), an ensemble consisting of violin, viola, cello/gamba, flute, oboe d’amore/cor anglais and harpsichord which played and recorded both early music in many different combinations, as well as contemporary works specially written for them.

In 1952 he established the renowned Netherlands String Quartet, with Nap de Klein, Paul Godwin and a very youthful Jaap Schröder. He formed the ensemble Sonata da Camera, with the violinists Willem Noske and Piet Nijland and harpsichordist Hans Schouwman, in 1958.

Significance

Boomkamp was a top-flight soloist who had toured extensively in a dozen countries by 1938, when he was listed in the Dutch National Biography; he was one of the founding fathers of the Dutch early music movement, and features prominently in Van der Klis (see below). He was an erudite collector of instruments and the teacher of generations of cellists and gamba players, all of whom he imbued with the spirit of historical performance practice. Although in later years he performed mostly in ensembles, he was particularly famous for his interpretation of the Bach cello suites, and was the first to play the sixth suite on a violoncello piccolo (using a re-imagined instrument made by Möller, who didn’t believe that such a thing had ever existed).

In Holland, he was a much-loved and respected institution and when he died, in 2000, significant obituaries appeared in all the major newspapers and musical magazines.

Acknowledgments

Once again, that excellent book, Oude muziek in Nederland, by Jolande van der Klis, has been a valuable source in writing this post; the English translation of various quotes is my own. Thanks are also due to Jaap Schröder.

© Semibrevity 2018 – All rights reserved

Thank you very much for Boomkamp’s biography! Brilliant man to know, and I enjoy getting to know my friend Jaap Schröder’s colleagues better.

I was lucky to study privately with Carel van Leeuwen Boomkamp during my gymnasium [grammar school] years. To me the cello always was exciting but I didn’t like the professional cello world, which I knew only from records. He opened up a new world for me, a world of beautiful sound. He made many interesting remarks during the lessons, which I will never forget. His system of cello playing was as clear as water to me. Disliking steel strings (he would call the colleagues who played on them the ‘Staalmeesters’ [steel masters]), it was the pure beauty of gut strings that came right into my heart. He told me that the decision to become a professional cellist was made during a [childhood] sickness, while his mother played a record of Casals. This sound was intoxicating and he gave up any resistance. Looking back, I think there was a little weakness in him – little I say – concerning business affairs, and a small unnatural stiffness in his playing in later years, being heavily praised and seen by many as the professor of cello – with outstanding pupils. His book on performance practice is a proof of intelligent thinking, first of all, and testimony of independent, creative living with and for the music. The two and a half years in his study-room with his collection of instruments on the walls remain a great gift all my life.